From “Separate but Equal” to “With All Deliberate Speed”

The Supreme Court’s May 1896 decision in Plessy v. Ferguson cemented the Jim Crow social order in its declaration that separate spaces for Black and White Americans were “equal.” It was not until Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 that the era of legalized racial segregation began to be chipped away…

In this issue

The Foundations of Separate but Equal

While the Emancipation Proclamation as well as the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments were important steps in the fight for civil rights, they did not outright stop the racism faced by the African American community. During Reconstruction, free Black Americans faced enormous challenges when they tried to do things as simple as book a hotel room, eat in a restaurant, or, in Homer Plessy’s case, ride a train.

Homer Plessy’s case began when he boarded a train departing from New Orleans, just years after the Louisiana state legislature passed a law requiring separate cars for Black and White passengers. An activist himself, Plessy boarded the car as a part of a plan with a Black citizen’s association to test the law. After Plessy’s refusal to vacate his seat in the Whites-only compartment, Plessy and the citizen group challenged his removal in the courts.

In May 1896, the United States Supreme Court delivered a decision that reverberated throughout history, shaping the nation for decades to come. Plessy v. Ferguson handed down the infamous “separate but equal” declaration, maintaining that the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause could not restrict states from carrying out segregation under the guise of equality. Ultimately, this ruling legitimized a “Jim Crow” social order whereby Black and White Americans could be legally segregated.

RG 267 Judgment in Plessy v. Ferguson

National Archives Identifier: 1685178

RG 11 Joint Resolution Proposing the 14th Amendment

National Archives Identifier: 1408913

Jim Crow’s America

But the separate spaces that the Supreme Court defended did not amount to equal.

In 1909, against the backdrop of the segregation protected by the Plessy ruling, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) emerged as a beacon of hope, continuing the work of testing the law as Homer Plessy did. With a mission to fight for civil rights and equality for African Americans, the NAACP embarked on a journey of legal challenges and grassroots activism that would bring the case law closer to desegregation.

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, the NAACP forged ahead with its legal strategy, challenging the “separate but equal” doctrine in courts across the nation. Landmark cases such as Gaines v. Canada (1938), which held that an African American student’s denial from law school in Missouri violated the 14th Amendment, struck blows at the pillars of segregation, laying the groundwork for future battles against inequality.

The Classroom as an Incubator

In April 1951, African American students at Moton High School in Prince Edward County, Virginia, went on strike to demand a better school. Led by 16-year-old Barbara Johns, the students demanded larger classroom spaces, better teacher pay, and more facilities (including a gymnasium) like the nearby White high school, Farmville, in the same exact county. Virginia had a law that mandated the segregation of public schools.

Exterior shot of Moton

National Archives Identifier: 76043372

Exterior shot of Farmville

National Archives Identifier: 279099

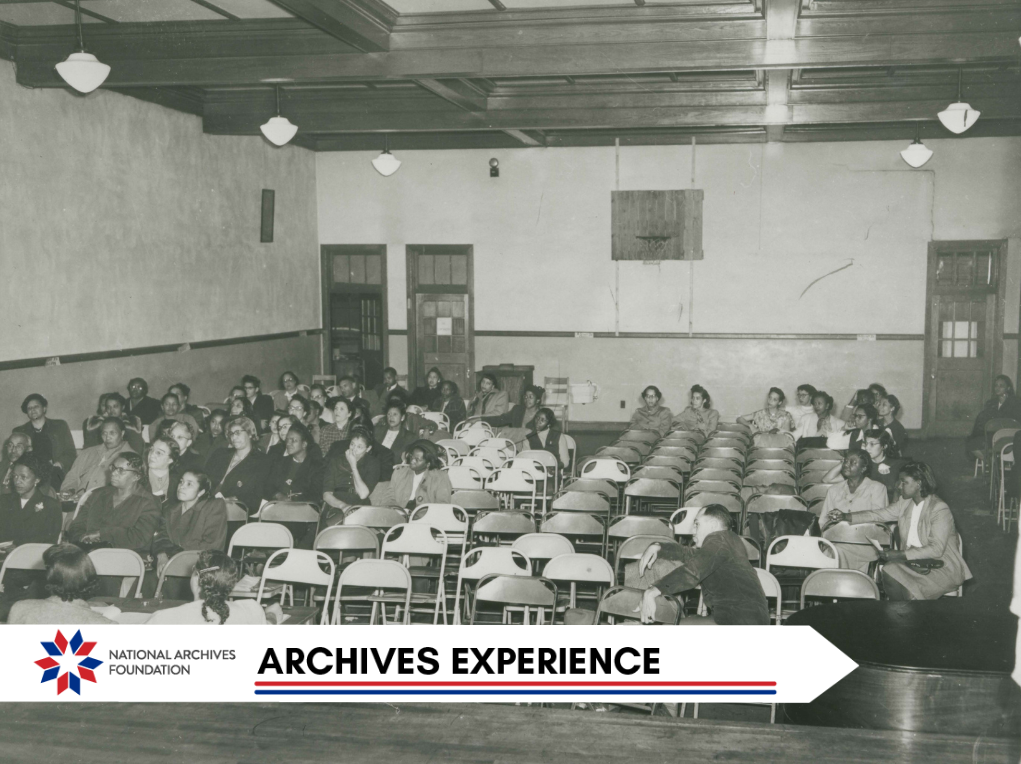

The students sought help from the local NAACP chapter, leading to a lawsuit against the school district. Plaintiffs aimed to challenge Virginia’s segregation laws by showing how separate facilities were in fact wholly unequal. Both sides presented photographs as evidence, illustrating the disparities between Black and White schools.

Auditorium in Moton

National Archives Identifier: 76043394

Auditorium in Farmville

National Archives Identifier: 76043338

“All Deliberate Speed” for All the Land

In 1952, the district court upheld the state’s school segregation legislation. However, the case was appealed and brought to the Supreme Court alongside cases from several states, including Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka.

Chief Justice Earl Warren delivered the unanimous opinion in 1954, noting decisively that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” All nine justices signed the opinion, which once and for all declared that the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause did not allow for different treatment on the basis of race.

RG 267 Opinion in Brown

National Archives Identifier: 1656510

Many states resisted desegregation and actively sought to maintain the status quo following the Brown decision. For this reason, another case, Brown II, followed the 1954 decision the very next year. It was necessary because the original Brown ruling lacked specific guidance on how to implement desegregation in public schools. While the 1954 decision declared that segregation in public education was unconstitutional, it did not provide a clear timeline or method for desegregating schools.

Ultimately, Brown II tasked lower federal courts with overseeing the implementation of desegregation “with all deliberate speed.” This phrase left room for interpretation and allowed for delays and resistance from state and local authorities in desegregating schools.

While the scope of the Brown decision was narrow in that it only applied to public school districts, desegregation for public accommodations came via the Civil Rights Act in 1964. This set the precedent that segregation was a violation of equal rights enshrined in the Constitution.

The work of students themselves along with activists and lawyers in the NAACP is a testament to the enduring power of hope and the relentless pursuit of equality. Even in the face of legal challenges and in many cases violence, the many important figures who were a part of this process all played pivotal roles.

The Legacy of Brown v. Board of Education, 70 Years Later

In commemoration of the anniversary of the Brown decision, the National Archives hosted the below program to discuss the legacy of the case.

Enjoy remarks from Dr. Colleen Shogan, the Archivist of the United States, before the Honorable Michael K. Powell, President & CEO, NCTA-The Internet & Television Association leads a discussion between two former law clerks of Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall: Sheryll D. Cashin of Georgetown Law School and Randall L. Kennedy of Harvard Law School. This event occurred on Thursday, May 16, 2024 at The McGowan Theater at the National Archives Museum and Online.

The Legacy of Brown v. Board of Education, 70 Years Later

(1 hours 33 minutes 31 seconds)

Presentation begins at minute 6:00

Source: US National Archives YouTube channel

This discussion reflected on the significance of Brown v. Board of Education and its impact on our nation’s pursuit of equality and justice.