Necessity is the Mother of Invention

This weekend is Mothers Day, designated since 1914 as a day to celebrate mothers, stepmothers, grandmothers, mother figures, and caregivers alike. But since we’ve told you that story before, we needed to invent a new twist for this Mother’s Day edition.

Women influencers predate the dawn of our nation. They helped shape the trajectory of society and history. A few famous and many more lesser-known female inventors and creators have found solutions to problems, engineered entertainment options to bring family together, and made life more efficient.

The Archives is home to thousands of patent records. These holdings are a fantastic snapshot of our nation’s inventive side, with the iconic alongside the ordinary and a lot of real oddities. This week, we share a few creations and shine a light on those women who didn’t get due credit back in the day.

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

Do Not Pass Go

National Archives Identifier: 7268011

In 1924, Elizabeth Magie Phillips was issued a patent for The Landlord’s Game, a collaborative game meant to demonstrate how rents impoverished tenants and enriched property owners. Phillips’ game was collaborative among its players and protested the actions of billionaires. In a way, her game predicted the Great Depression, foreshadowing the hardship that befalls the majority when one player ultimately makes all the money.

National Archives Identifier: 12043374

But in the middle of the Great Depression, in 1934, Charles Darrow patented his game, Monopoly, sold it to Parker Brothers, and made a fortune. Although Monopoly featured a game board conveniently similar to The Landlord’s Game, its premise was the exact opposite: the winner gobbles up all the real estate and drives their competitors into bankruptcy. In the midst of the worst economic downturn in history, the game was a celebration of capitalism, and, at least according to Phillips, demonstrated the corrupt nature of big business. Although Phillips’ game and layout came first, it’s Darrow’s cutthroat game we play today. You can blame him for the hours-long marathons that rip even the closest-knit families apart by the game’s end.

Big Eyes, Bigger Lies

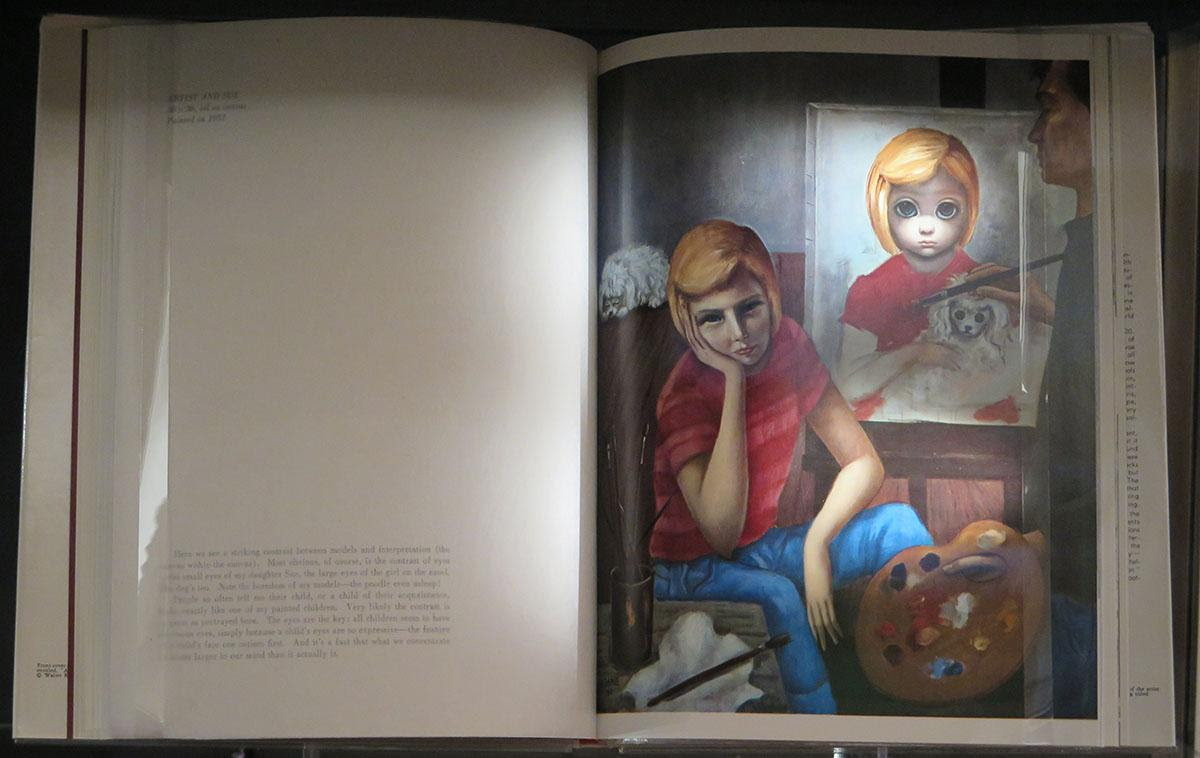

Source: Nixon Library

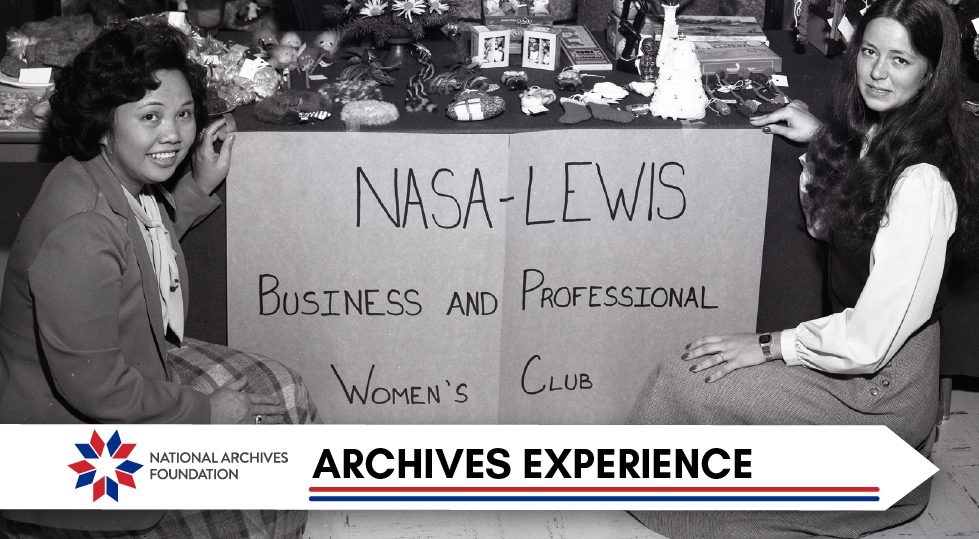

The creator of the Keane Eyes paintings, Margaret Keane, has been painting for more than sixty years. Born in 1927, in Nashville, Tennessee, she married Walter Keane in 1955, and he began selling her “big eyes” paintings, but he soon claimed he was the artist. Margaret went along with the deception for years, consoling herself with the fact that the work was being shown and sold.

By the 1960s, Keane’s work was among the most commercially successful of the era. The Big Eyes paintings were both lauded and excreted. Finally, in 1970, Margaret announced on a radio broadcast that she was the artist who created the paintings. In 1986, she sued Walter and USA Today because the latter had published an article stating that Walter made the paintings. The judge in the case ordered the two of them to each create a painting in the courtroom. Walter declined, claiming his shoulder was sore, but Margaret painted a Big Eyes work in less than an hour. The judge ruled in her favor and awarded her $4 million in damages.

In 1969, Walter Keane gave President Richard Nixon a first edition “Walter Keane” that is now the property of the American people.

In the years since she moved out from Walter Keane’s shadow, Margaret Keane has continued to paint her Big Eyes works.

Renaissance Woman

National Archives Identifier: 7268010

The next time you’re driving in bad weather, and you turn on your windshield wipers, think of Mary Anderson, the woman who invented the windshield wiper.

Anderson was born in Green County, Alabama, in 1866, and lived mostly in the South her entire life, but during a visit to New York City in 1902, she was riding a trolley during a sleet storm and observed that the driver had to keep reaching outside of the vehicle to wipe the window clean. When she went back to Alabama, she designed a hand-activated wiper, had a local company build a model, and applied for a patent for it. She had no luck selling her invention, however, probably mainly because at the time, cars were not very common.

Paper or Plastic?

National Archives Identifier: 176530307

If you are trying to think more sustainably and use more paper bags than plastic bags these days, you have Margaret E. Knight to thank for that convenience. Knight was born in York, Maine, in 1838, and moved with her family to New Hampshire after her father died when she was twelve. At a very young age, she went to work in a cotton mill to help her mother support the family. Knight had a keen, creative mind, and she was soon coming up with improvements to the equipment in the mill to make it safer and more efficient. She didn’t know anything about the patent process, however, and consequently she lost the rights to several improvements she had designed to the cotton looms.

Knight went to work at the Columbia Paper Bag Company in Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1867. At that time, workers made each paper bag by hand. Knight designed a machine that took paper in, cut it, folded the square bottom of the bag, glued the bag together, and then pushed the completed bag out.

She then applied for a patent, but one of her co-workers, Charles Annan, tried to steal her work, saying that she could not possibly understand the complexities of the machine she had invented. She proved him wrong, won her case and her patent application, and went on to found her own paper bag company, the Eastern Paper Bag Company in Hartford, Connecticut. She continued to work on new innovations throughout her life.

Margaret Knight was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2006. She holds at least twenty-six patents.

Act Quickly

Source: NARA’s Prologue blog

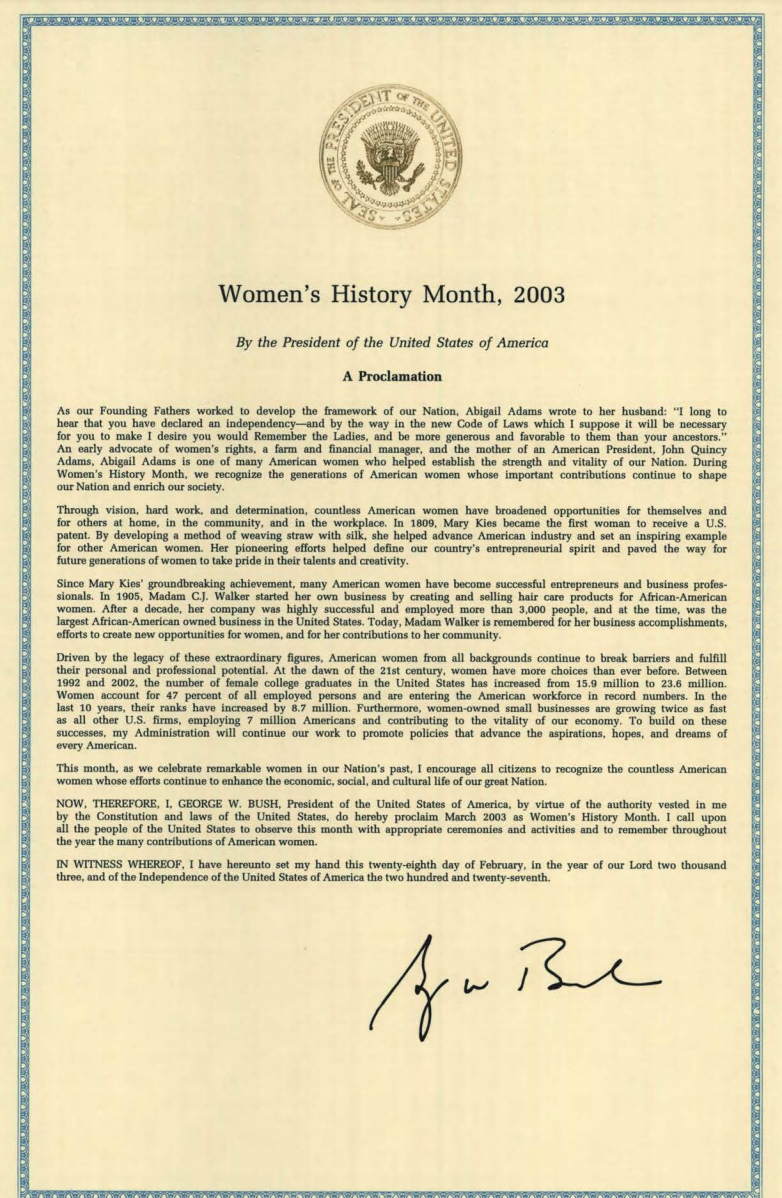

The first woman to apply for a patent in the United States truly was acting out of necessity. In 1807, France was at war with Britain, and although the United States was trying to stay neutral, both Britain and France were seizing U.S. ships and cargoes as war contraband. Furthermore, the British forcing American sailors into the Royal Navy, which outraged the United States. In response, at Thomas Jefferson’s urging, Congress passed the Embargo of 1807, which stopped all foreign trade with the U.S. and nearly crippled the young nation’s economy.

National Archives Identifier: 134609934

Unable either to import necessary commodities to support their industries or to sell their finished products to foreign countries, both industries and individuals were forced to be resourceful. Mary Dixon Kies, an inventor who lived in Brooklyn, New York, came up with a method of weaving silk or thread into straw that could be used for making bonnets. It was a huge success—her hats soon became the latest fashion sensation.

Kies applied for a patent under the 1790 Patent Act. President James Madison signed her patent in 1809, and First Lady Dolley Madison wrote her a congratulatory letter. Her invention helped keep the New England hat industry thriving for many years.

Mary Dixon Kies’ patent is one of only twenty patents awarded to women in the United States before 1840. Like Margaret Knight, she was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2006. Three years earlier, her achievements had been recognized by President George W. Bush in a Women’s History Month Proclamation.