There’s A Place for Us

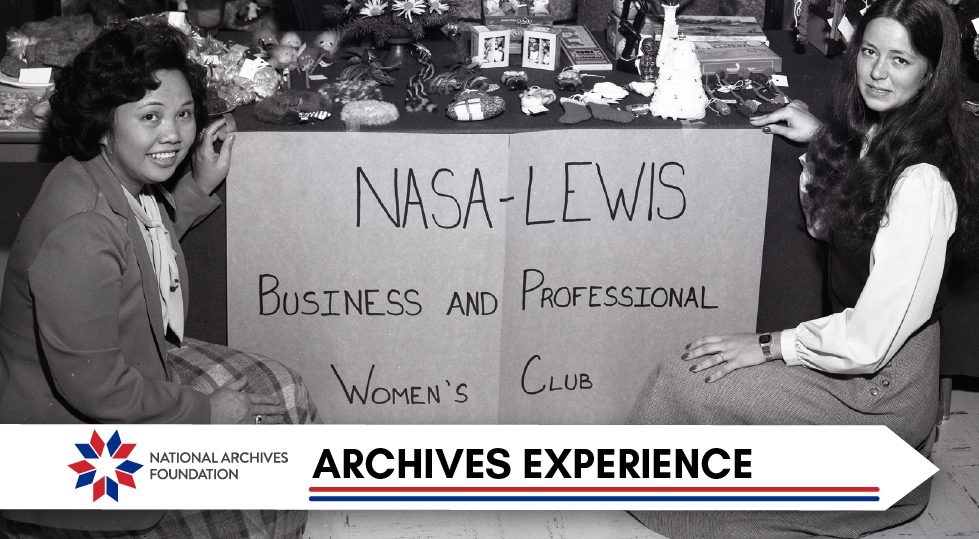

For the majority of our country’s history, women were excluded from civic and public life and limited by gender norms and social conventions. With limited spaces in public, women turned to community building around each other and began creating not only spaces, but also communities that would change the fabric of society.

Dormitories and community centers weren’t just physical spaces–they were a refuge from violence, a place to jumpstart economic independence and a venue to socialize and organize with other women outside of the home.

Sometimes historical places are just as important as those who inhabited them. For women’s history month, we’re taking a look at the all-women’s spaces that were the catalysts for many of the achievements celebrated during Women’s History Month.

In this issue

History Snack

A 700-room Sorority

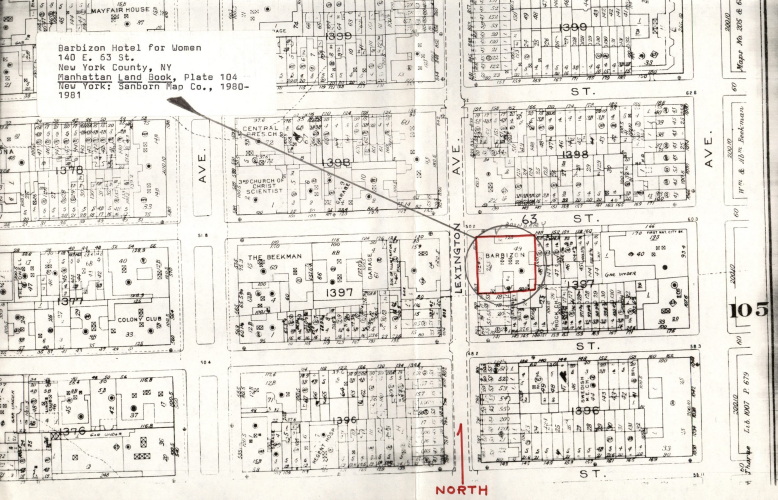

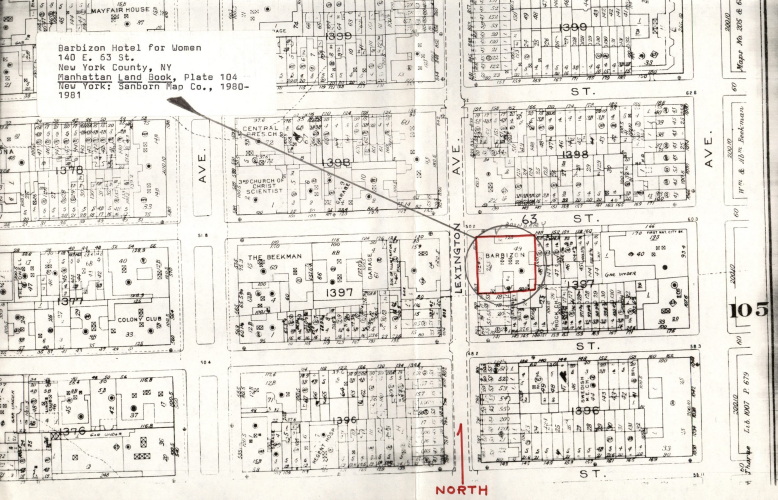

The Barbizon Hotel, located at 63rd Street and Lexington Avenue in New York City, began its life as a residential hotel for young career women who were looking for a place to live in the big city. Built in 1927, the hotel was one of more than 100 such institutions in New York that included the Plaza and the Algonquin. Unlike those hotels, however, the Barbizon from its inception was strictly for women only, and as recently as 2021, according to The New Yorker, a few women still lived in small apartments on the upper floors of what is now mostly a condominium building.

Unlike other residential hotels, the Barbizon primarily catered to women working in the arts, such as publishing and the theater, or who worked for modeling agencies or were attending Katherine Gibbs Secretarial School. A young woman had to produce letters of recommendation to be accepted as a resident of the Barbizon, and men were not allowed on the residential floors unless they were doctors or tradesmen who were working on specific projects, like a busted water pipe.

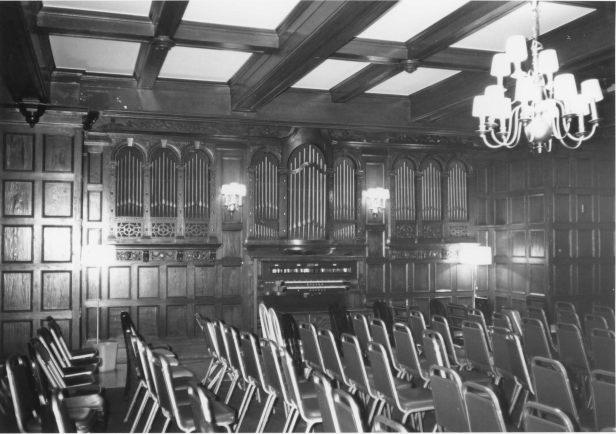

The Barbizon accommodated about 700 women in its 23-floor building, which housed a library, a gymnasium, a swimming pool, music rooms, lecture halls, a garden on the roof and businesses on the first floor that included a pharmacy, a hairdresser, a dry cleaner and clothing shops.

The hotel was rather famously home to writers like Joan Didion and Sylvia Plath and actresses like Liza Minnelli, Grace Kelly and Cybill Shepherd. It managed to weather the tides of social change through the end of the Roaring Twenties and World War II, the upheaval of the Vietnam War and Second Wave Feminism, but the real estate boom of the 1980s ultimately put an end to its life as a residential hotel for women only. However, when the owners of the hotel tried to oust their long-term residents so they could spruce it up and rent the rooms out at much higher rates, the Women, as they were called, hired a lawyer and won the right to retain their rent-controlled apartments.

On Valentine’s Day 1981, men were allowed to book rooms at the Barbizon for the first time. The building passed from one owner to another until 1998, when the Berwind Property Group bought it, renamed it the Melrose Hotel at the Barbizon and announced it was converting the building into condos. When the renovations were done, the former tenants moved back into their rent-controlled apartments at the same rates they’d been paying all along, some of them for decades.

Catch a Break

In 1917, the U.S. Department of Agriculture noted in its annual yearbook the emergence of a new movement in agricultural communities, mostly in the Midwest and West, that it identified as the “Rest Room movement.” These were spaces, sometimes a group of rooms and sometimes entire buildings, set aside specifically to “meet the needs of the country woman in town on business. They provide a place, where the farm woman has a right, without asking any favors, to the use of facilities for rest and refreshment.”

Mrs. Rutledge Smith of Cookeville, Tennessee, had first brought up the idea in that state when she made a speech at a convention of homemakers in the fall of 1912. Smith had urged the county officials to set aside space in the county courthouses for country women who were accompanying their farmer husbands to town where they could freshen up, put their children down for naps, meet other women from the country and from town, read and relax. The idea caught on, not in small part because it appealed to the merchants in the towns who were eager to encourage farm wives to shop while they were in town, so the salesmen could show them their newest labor-saving devices and urge them to persuade their husbands to buy them.

By the time the U.S.D.A. report was written in 1917, more than 200 women’s rest rooms had been opened across the country. The Ladies’ Rest Room in Lewisburg, Tennessee, on the National Register of Historic Places, is a perfectly preserved example.

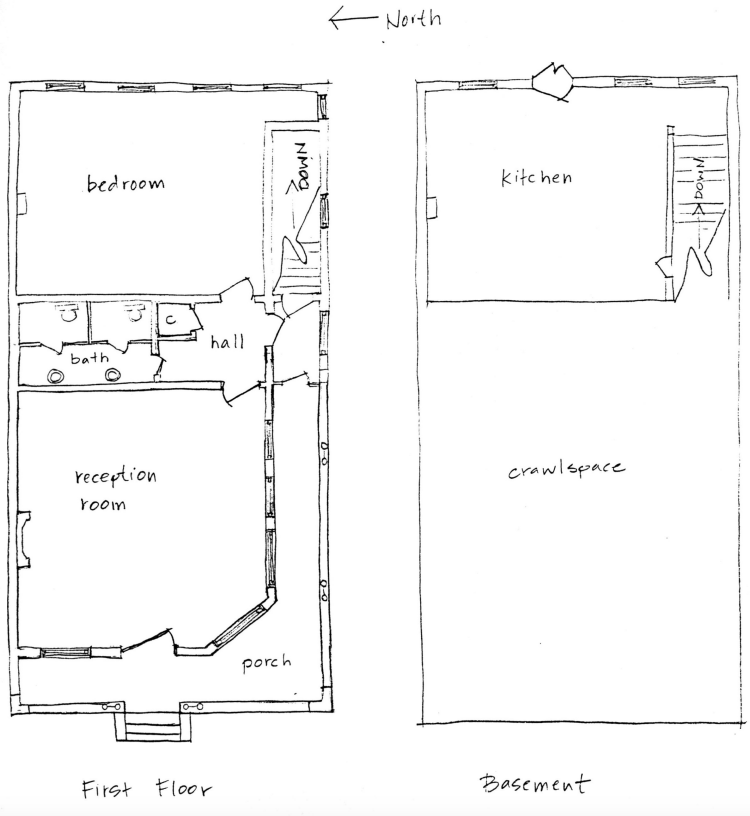

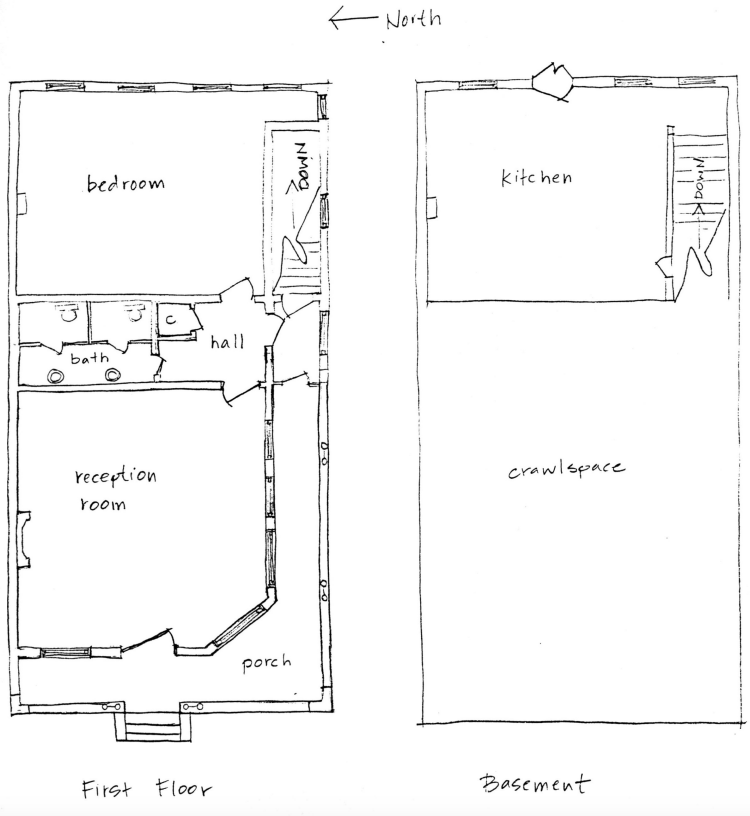

Designed, constructed and dedicated in 1924, the Ladies’ Rest Room was immediately well received by the community. Fanny Allen Liggett, the home demonstration agent for Marshall County, described it as “the nicest and most complete rest room in the state . . . . really a complete building consisting of a reception room, hall rest room, and toilet upstairs and a large dining room in the basement.” The rest room became a gathering place for the women of the county on Saturdays and court days, when their men were attending events at the courthouse or shopping in town. The Ladies’ Rest Room is still open for public use.

It’s Fun to Stay at the…

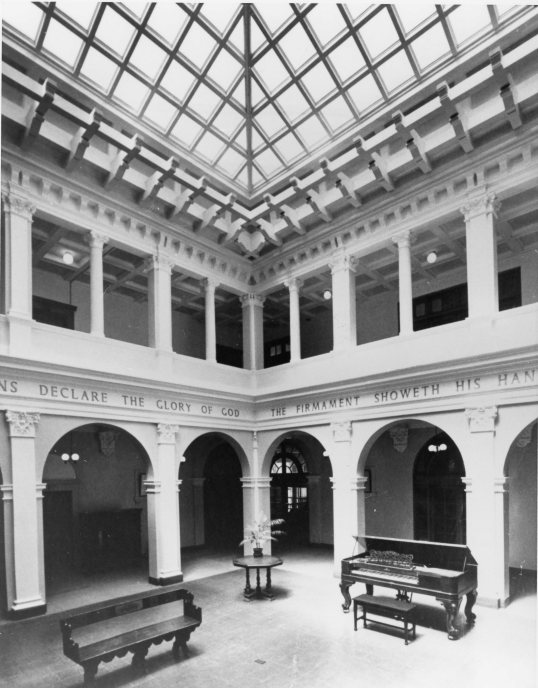

The organization that grew into the Young Women’s Christian Association was first established in London in 1855 by Lady Mary Jane Kinnaird as the North London Home to provide shelter for nurses who were traveling back and forth from the Crimean War. The home also offered shelter and support for young women who were coming to London to work in the new industries that were opening up then. In 1877, the home merged with Emma Roberts’ Prayer Union. In 1884, the organization restructured yet again, with the London home merging with similar organizations in the rest of England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland, and foreign branches. In 1894, the founding members of Great Britain, Norway, Sweden and the United States established the World YWCA, with the mission of protecting young women from the social ills of the time and spreading the gospel of Jesus worldwide.

Just after the turn of the 20th century, however, the mission of the YWCA gradually changed to a more secular emphasis, in part because of the emerging influence of socialist movements and also because the international organization moved its headquarters from London to Geneva, Switzerland in 1930. Furthermore, local chapters of the YWCA have proven remarkably nimble at identifying the needs of their communities and finding ways to fulfill them. Particularly in the United States, where individual iterations of the YWCA were often established in communities that were widely separated geographically and often served very diverse populations, the chapters have evolved to accommodate the needs of their communities.

The Ladies’ Christian Association, established in New York in 1858, is considered the first American manifestation of the organization, although the Boston YWCA, founded in 1866, was the first to use that name. The initial function of the YWCA was to provide housing for young working women who, for the most part, had just left home, but in Boston, it soon became apparent that these young women needed more support than just housing—they also needed educational opportunities and places where they could meet and socialize without putting themselves at risk, as they might in dance halls and barrooms.

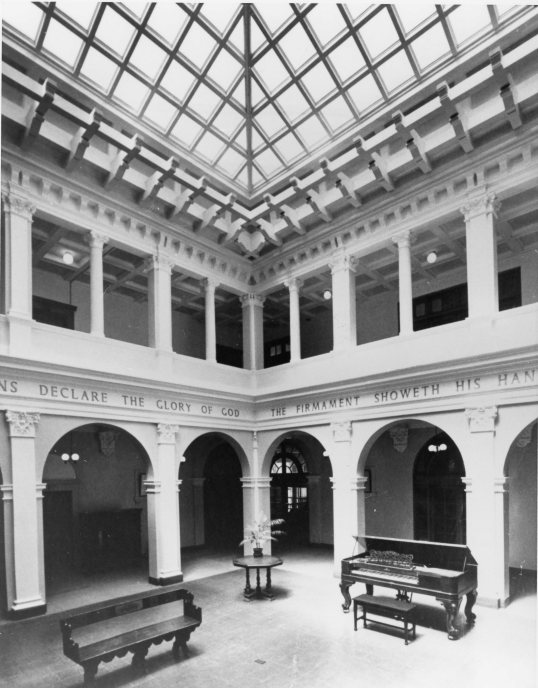

The good people of Boston responded by raising $1.5 million to build a proper home for the YWCA and to create a fund for its maintenance. Construction began in mid-1927, and the new building was dedicated in 1929. It boasted 14 stories, nine of which were set aside for activities, three for temporary guests and two with apartments for professional women. The building had a swimming pool, two recreation halls, reading rooms, a gymnasium, bowling alleys, a lounge and a coffee shop. The administrators intended that all these facilities would improve the lives of the young women they served and help them advance themselves as productive citizens in society. The Board of Managers also voted that year to allow any young woman of any creed or race to join the organization.

The Ladies Evangelical Philanthropic Society in Oakland, California, a group of women from churches of different denominations in Oakland, California, banded together in 1877 “To establish a sheltering home for girls without home or friends. To gather children together to teach them helpful things. To visit jails and hold prayer and Bible readings with the women. To interest themselves in ‘girls’ who are on the ‘wrong road’ and leading others on. To make our name loved and respected, in Oakland because of the good we do for women and girls.” A year later, the group affiliated with the national YWCA movement, thus becoming the first such organization in California.

Like most of its sister institutions, one of the Oakland Y’s principal functions was to provide affordable housing to young women who were entering the workforce, especially those who were moving to the city from rural areas. Over time, the Y began to offer more services to its members, but the advent of World War II in particular threw the YWCA’s social services functions into higher gear. The organization created a dormitory for WACS, fed defense workers at a 24-hour “Back Door Canteen” and ran Youth Harvest Camps that hired teenagers to do agricultural work to replace adult workers who were deployed or were working in other war industries.

Since the war ended, the Oakland YWCA has created programs for teenagers, the handicapped and ethnic groups. It offers classes and recreational opportunities to individuals of all ages, ethnicities and sexes year-round.

This movement away from the religious and toward the secular is reflected in the change of the name of the national organization in 2015 in the United States to “YWCA USA, Inc.” “In our early years it was ‘a Christian sisterhood’ that drove our work,” the U.S.’ chapter website states. “Today, our organization is driven by a commitment to social justice, no matter someone’s religion. Our updated name provides YWCA with the opportunity to engage a broader spectrum of individuals in our crucial work to eliminate racism and empower women.”

View this profile on Instagram

National Archives Foundation (@archivesfdn) • Instagram photos and videos