Family Story Time

At some point during Thanksgiving dinner festivities, conversations drift to family lore. Maybe you will hear stories of a relative who saw action in a war, or a disastrous recipe experiment, or a classic story about a beloved family pet. For me, there is the tale of the fraudulent family photo. It is well established – and factually accurate – that I am solidly five inches taller than my older brother. Yet, in a family photo about 15 years ago, the photographer gave my brother two phone books to stand on to “balance out the photo” as we were standing on each end of the family. And now, he is the same height as me in the 8×10 framed photo on my mom’s mantel, and this false lore will be perpetuated for generations! My brother LOVES to tell this story. Me? Not so much.

I’m fortunate to have relatives who are amateur family historians. They have filled in the family tree and have done an amazing job documenting our family connections. But for many, the tree is incomplete, and the stories are left untold. Family researchers have been using the National Archives for decades to pore over records and discover lost family members. This week, we’re featuring three genealogists and the Archives records they used to make discoveries about their own families. Join us as we bring these stories from their Thanksgiving table to your inbox.

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

Mich and Maye

Photo courtesy of Mich Lundgren

Mich Lundgren explains how filling out her 2020 census form led her to family members previously lost to history.

In 2020, I begrudgingly filled out my census form, mildly bothered by the government keeping tabs on us. Imagine my surprise when a year later, a census record changed my life. The journey to identifying my great-grandmother’s birth parents led to an illogical theory and months of research to unravel the mess of my great-great-grandfather’s life. Ultimately, that theory proved true, and it delivered the key to something I didn’t know I’d been searching for: it helped me finally find myself.

My great-grandmother Maye Nordby was adopted in 1914 at the age of two. Nobody in my family knew who her birth parents were, but when I inquired, two people mentioned that late in her life, she began going by Maye Zimmerman rather than any of her known surnames. This was the clue I needed – and he was right in plain sight. In the 1920 federal census, Walter Zimmerman was listed as living with Maye and her adoptive family in Steele County, Minnesota, as a hired hand. Her father.

View the 1920 US Federal Census Record

I discovered that his wife, Ella (Cain) Zimmerman, had passed away after the birth of their youngest son, and all of their eight children, including Maye, were adopted out. It was easy enough to piece together the lives of the children, but I was left with a quietly nagging question: what happened to Walter?

My search for Walter began with a 1934 marriage license and a man who in 1930 was a widowed father of three little boys, living two states away, with too many wrong details. There is no reason to suspect this was my great-great-grandfather, and yet my gut told me he was. I slowly pieced together the twisting tale of his life, finding his three dead wives and a stolen child who has yet to be fully recovered. I traced his life through incorrect census and vital records, half-mentions in obituaries, and many leaps of faith that proved true when I uncovered the documents that verified my hunches. I compiled all the information, created a spreadsheet to share my research, and approached the family we’d been separated from generations back.

View the 1930 US Federal Census Record

View the 1940 US Federal Census Record

I thought I would have to present my data and defend my conclusions, but instead, my newly discovered first cousin told me it was all true and that it’s a well-known and unspoken fact in that family. Then she sent me a photo, shown in this article, of Walter and Ella, my great-great-grandparents – and there was my own face staring back at me, from a hundred years ago. Ella Cain was the source of the face I’d never been able to find. However, there was a bigger truth here, and in the space between her and myself, I saw nothing but the wreckage that followed her death. All the terrible choices, abandonment, and abuse that have trickled down through the generations to rest on my shoulders, threatening to continue on to my children. Can a pile of historical documents and a wild but true story be enough to help me create change? Can I use it to weave together a new legacy, to begin to create a new story for our family line of grace, healing, and redemption? I’d like to believe so.

Generational Impact

Photo courtesy of Lauren Peightel

Lauren Peightel isn’t just on a search for family history – she’s looking to put the emotional connections back into genealogy research.

For the last five years at the Indiana Historical Society, I’ve been helping people connect to the past with creative programming and classes, conferences, and fun events that help them discover their personal family histories. Exploring some of my own history, I’ve been utilizing digital image and movie collections about the D-Day invasion of Normandy to answer questions about my family’s experiences and patterns with transgenerational trauma and silence. These patterns extend from the generations before my grandfather to his World War II naval service, to my uncle and his service, and to the silence around my cousin’s death.

Here’s a personal family photo image of my grandfather, Morris Rodney Farrell, USNR SV-6 Coxswain. On D-Day, he was a seaman on LST 504. My Pap dealt with health issues like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, so this journey into his service has been a way for me to connect with him. Additionally, violence and warfare were against his strong Brethren faith, but he never spoke about this. Ever. Upon returning home, he dealt with PTSD and refused to travel. Using all sorts of primary and secondary sources was necessary for me to better understand his experience and the profound impact it has had on the family for generations. Besides ordering his personnel file from the National Archives in St. Louis, I’ve been reviewing all images and film associated with D-Day and the campaigns he was part of in the Mediterranean and South Pacific.

This emotional work is accomplished through a research method I created at the Indiana Historical Society called IN 4D that teaches researchers to use sensory-based experience questions to guide their searches. Such questions function as stepping-stones to better storytelling that can actually affect the future. These videos and images will be instrumental to my next course about looking at my grandfather’s service in World War II.

I have also utilized Founders Online records to find out more about my direct ancestors Rebecca Smith Blodget (her letter to President Madison) and her husband Captain Samuel Blodget, Jr., and his business with Jefferson and Washington in planning the city of Washington, D.C. Rebecca and Samuel led very public and scandalous lives, and my journey into who they were and what they did started when I stumbled upon Sam’s and Rebecca’s letters in Founders Online.

Read Rebecca’s full letter dated

March 11, 1809

in Founders Online

Most historians of early America and the federal city focus on Sam’s foibles, but I’ve become much more interested in the rise and fall of his wife and her relationship with Aaron Burr after finding this letter in the collection.

Found in NYC

Dr. Adina reflects on how records at the Archives’ New York City facility led her to an undiscovered part of her family tree.

My great-grandfather, Simon Rosenthal, has always been the most difficult member of my family to trace. With conflicting evidence concerning his exact origins and no known family who immigrated to the United States with him, I initially wasn’t too sure where to look.

However, I had a major breakthrough when I found a ship manifest for a “Schie Rosenthal” who listed my great-grandfather as his uncle and point of contact. Within the entry, I found that Schie had pursued naturalization, likely in New York City.

Further research revealed that Schie became Samuel, and his wife and daughter immigrated shortly thereafter. Three more children were later born in New York City.

Naturalization records digitized by NARA New York City were my keys to learning more about these relatives. NARA NYC had digitized the naturalization records for the Eastern District from 1865–1958, which was where I found his daughter, Anna’s, naturalization records. Samuel reported his birthplace as Zaslav (now Izyaslav, Ukraine), which could mean the area, but also provides a potential avenue for research on my great-grandfather’s family. Photos of my ancestors are particularly important to me because they bring the records to life. Fortunately, Samuel’s and Anna’s declarations both included photos, which I have added to my collection.

View Samuel Rosenthal’s Declaration of Intent

Caring for Family Archives

If you’re entrusted with family records like letters and photos, you might be wondering how to preserve them for your descendants. The National Archives is here to help!

Here are some very useful tips for ensuring those precious documents are around for the next several hundred years.

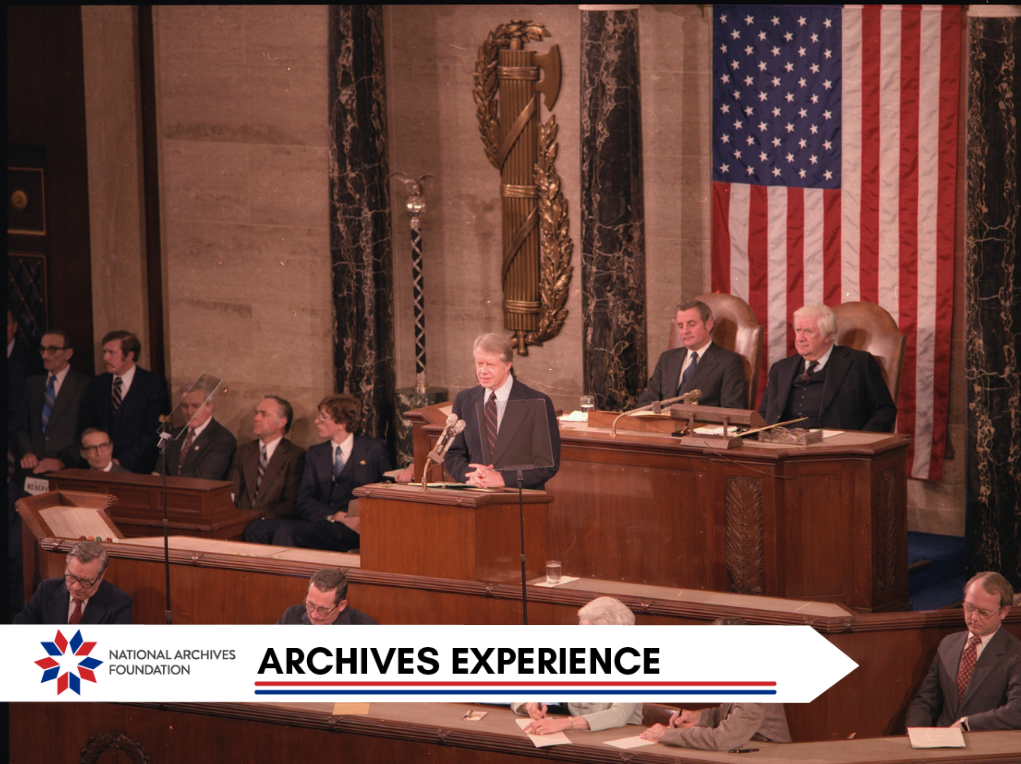

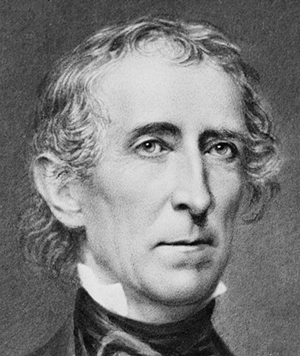

History: Closer Than You Think

View John Tyler’s Census Records

Lyon Gardiner Tyler passed away on September 26 of 2021. He was the grandson of U.S. President John Tyler, who was born in 1790. Tyler became the tenth President in 1841, after President William Henry Harrison died of pneumonia just a month after his inauguration. Tyler served one term and died in 1862.

It’s surprising that only two generations separated Lyon Gardiner Tyler and John Tyler, but the explanation is that John Tyler had two wives, Letitia Christian Tyler, who died in 1842, and Julia Gardiner Tyler, who married John Tyler in 1844. She was thirty years younger than her husband. Between them, Tyler’s two wives gave birth to fifteen children.

Think that this is too crazy to be real? The National Archives has the Census records of John Tyler and his family. History is always closer than we think.