The Promise of Freedom: History of Juneteenth

This week marks the anniversary of Juneteenth, when General Order Number 3 was issued in Galveston, Texas, nearly 160 years ago. June 19th is a special day of reflection and celebration when the people of Galveston learned of the existence of the Emancipation Proclamation and its promise of freedom for enslaved people in the United States. This week’s Archives Experience explores what led to this moment two and half years after Lincoln’s proclamation.

In this issue

A Proclamation

President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, when the nation was well into the second year of the Civil War. Lincoln’s proclamation, while controversial, was limited in scope, declaring, “All persons held as slaves within the rebellious states are, and henceforward shall be free.” Lincoln saw the proclamation as a necessary war measure for suppressing the rebellion. It only applied to the Confederate states, leaving out countless enslaved men, women, and children in parts of the Confederacy already under Northern control and in the loyal border states.

Emancipation Proclamation

National Archives Identifier: 299998

The proclamation faced opposition, even among supporters of the Union. Many of Lincoln’s advisors disagreed with it because it expanded the focus of the Civil War from preserving the Union to also freeing the enslaved. Lincoln’s own General-in-Chief of the Union Army, George McClellan, had been capturing and returning runaway slaves on his own volition and opposed the idea of changing the conflict’s focus.

General George B. McClellan

National Archives Identifier: 528744

In 1861, as the scale of Civil War was on the horizon, Congress attempted to pass an amendment, which would have become the 13th Amendment, stating the Constitution could not authorize the federal government to abolish state laws, including those that permitted “persons held to labor or service by the laws of said State.” The amendment failed, but had it been ratified, it would have guaranteed the right of slave-holding states to continue practicing slavery.

The failed amendment

House Joint Resolution (H.J. Res.) 80 Proposing a

Constitutional Amendment to Prohibit

Congress from Abolishing Slavery

National Archives Identifier: 24824293

Regardless of its limits, the Emancipation Proclamation was a step forward in limiting slavery and carried the promise of freedom that would only be realized after a Union victory in the war. The proclamation also provided for Black men to be allowed to serve in the military. By the war’s end, almost 200,000 Black soldiers and sailors had fought for the Union and for freedom.

In response, the Confederate Congress passed an act that declared the enlistment of Black troops was the equivalent of inciting a servile rebellion, that White officers of Black troops were to be executed, and that Black troops were to be taken prisoner and sent to states where they could be executed or re-enslaved.

Henry Stewart 54th Infantry Massachusetts

Source: NARA’s American Originals Exhibit

Courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston

A Union victory in early 1863 was anything but a sure thing. Months after the Emancipation Proclamation, Confederate General Robert E. Lee won a stunning victory at Chancellorsville, Virginia, and the Southern forces were planning to invade the North. It is not until July 1863 and the Union victory at Gettysburg that the war began to turn in the favor of the Union. Slowly but surely, the Union army was advancing southward. With each victory in each town and each state coming under Union control, enslaved people were finally free, as the Emancipation Proclamation had ordered. News of the proclamation was slow to reach those in Confederate states, and the slowest for it to reach was Texas. In other places, slaveholders hid the news to preserve slavery.

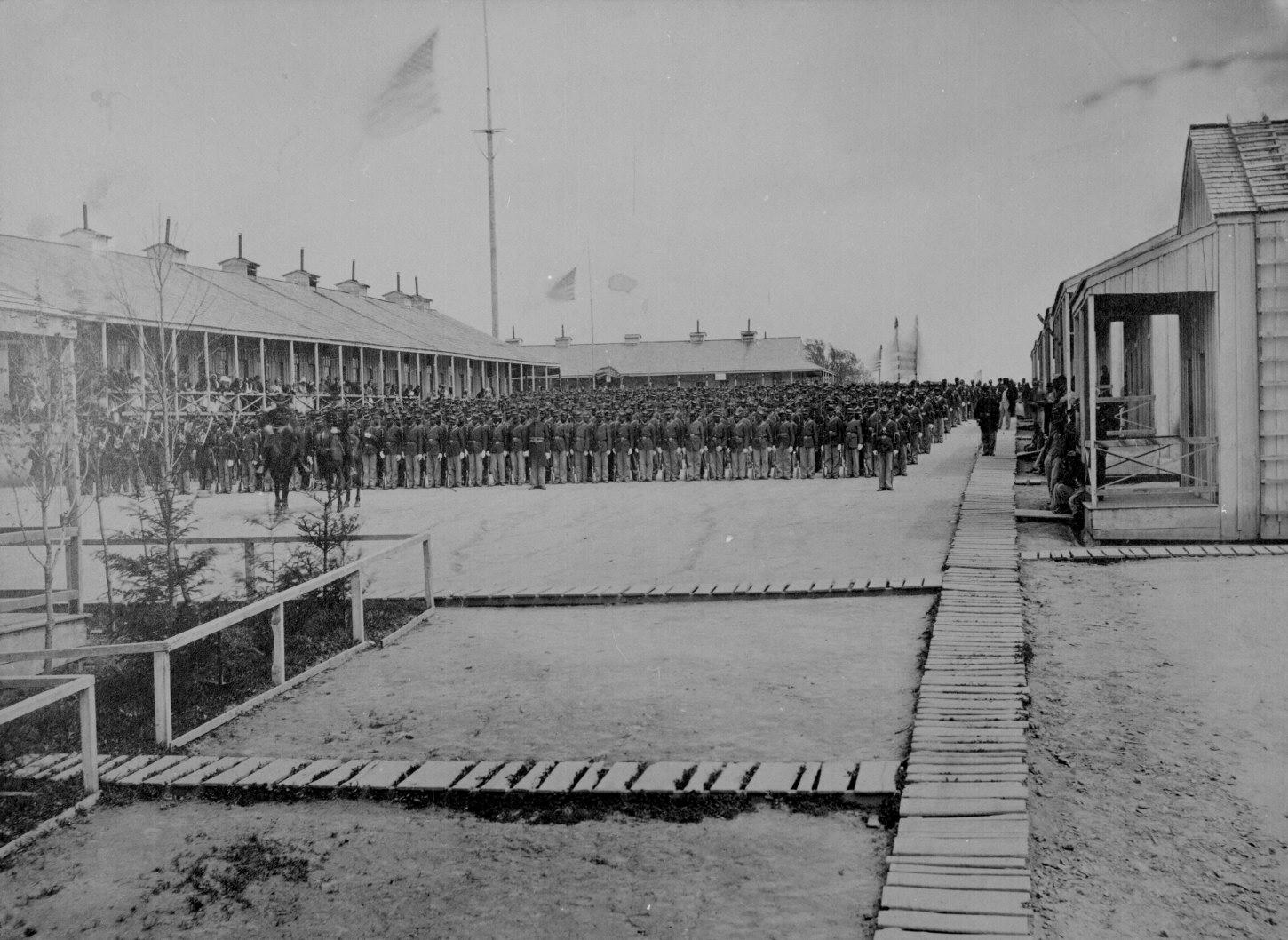

The 26th U.S. Colored Volunteer Infantry on parade, Camp William Penn, Pa., 1865.

Source: NARA Military Records Research > Civil War > Pictures

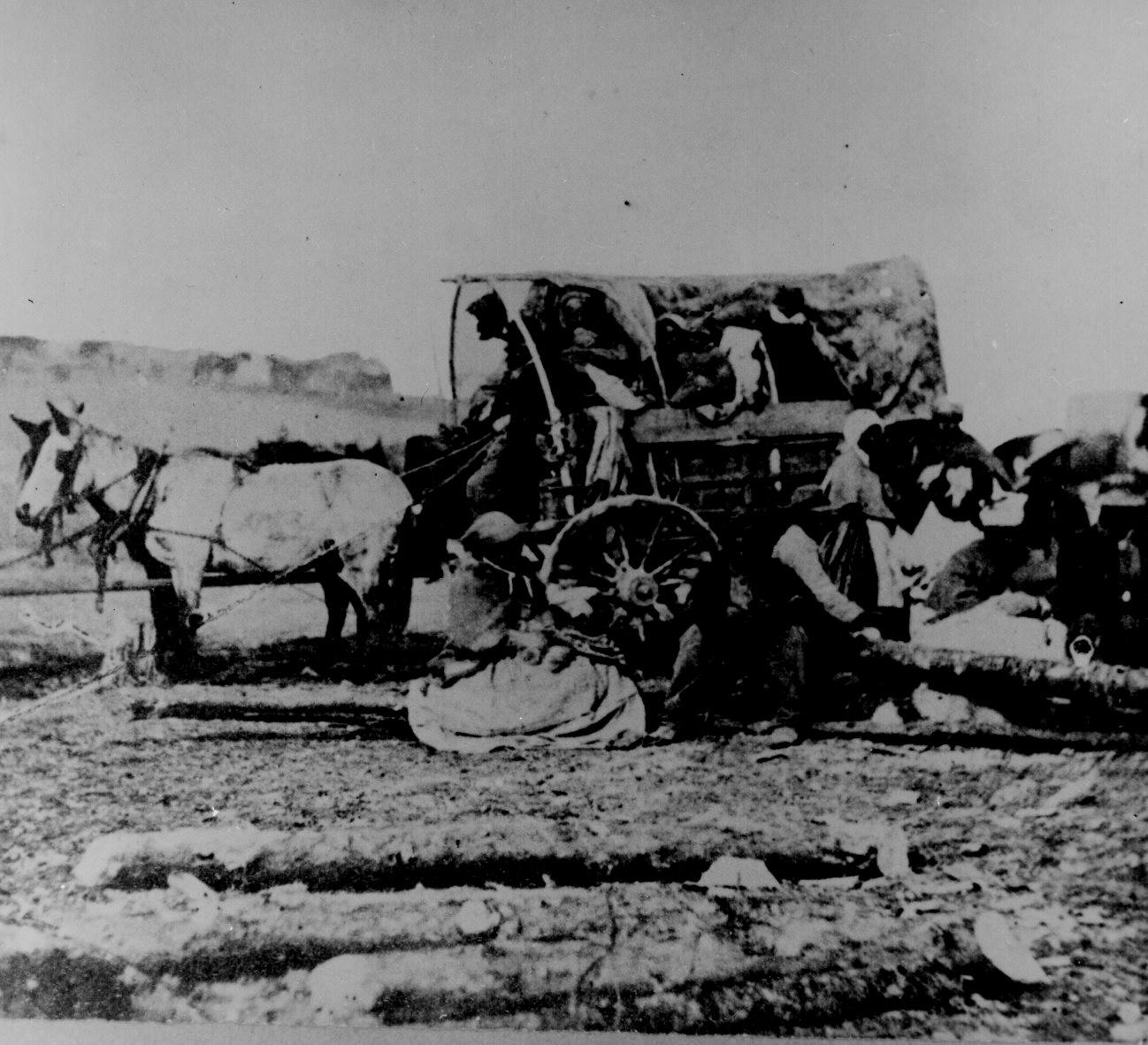

A black family entering Union lines with a loaded cart.

200-CC-657

Source: NARA Military Records Research > Civil War > Pictures

The News Reaches Texas

On June 19, 1865, U.S. Major General Gordon Granger, who had been given command of the District of Texas nine days earlier, issued the aforementioned General Order No. 3, which informed the people of Texas that, “in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor.…”

The order set off joyous celebrations at the time. The day has come to be known as Juneteenth, a combination of June and the 19th. It is said to be the oldest known celebration commemorating the end of slavery in the United States.

The last two sentences of General Order Number 3 stated, “the freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.” This foreshadowed the struggle for fair treatment and eventually led to the ratification of the 13th Amendment in 1865, which ended slavery in all states; the 14th Amendment in 1868, which provided citizenship, due process, and equal protection to all persons born or naturalized in the United States; and the 15th Amendment in 1870, which provided the opportunity to Black men to vote and hold office.

Juneteenth has become a day for all Americans to reflect and commemorate the struggles and sacrifices of enslaved Americans. In 2021, President Biden proclaimed June 19 a federal holiday recognizing the significance and lasting impact of this pronouncement.