Guiding Lights

Nights on the open water are as dark as it gets. Only under near-perfect conditions are sea captains able to sail under starry skies with a full moon as a guide. Centuries ago, it was only after days or weeks at sea that vessels were finally greeted by a light shining from the coast. Its message served dual purposes: to warn sailors of a treacherous shoreline and to act as a beacon of hope, welcoming them home.

The first lighthouses date back thousands of years to the ancient Egyptians and Romans. Lighthouses in the U.S. were built as early as 1716. Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, lighthouses dotted the coastlines of the U.S. Many of them were as beautiful as they were functional and included a tower, a keeper’s house, and other structures. Although many lighthouses no longer serve their original functions, they still act as a beacon. Lighthouses are popular tourist destinations, art inspirations, and even creative hotels and B&Bs, their beauty and rich history still drawing us to them. Today is National Lighthouse Day, and the Archives is home to thousands of records from the U.S. Navy, Coast Guard, and federal building projects that tell unique stories about every lighthouse. We’ve anchored a few favorites to share with you this week.

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

Navigational Hazard

Description of the party

National Archives Identifier: 6037497

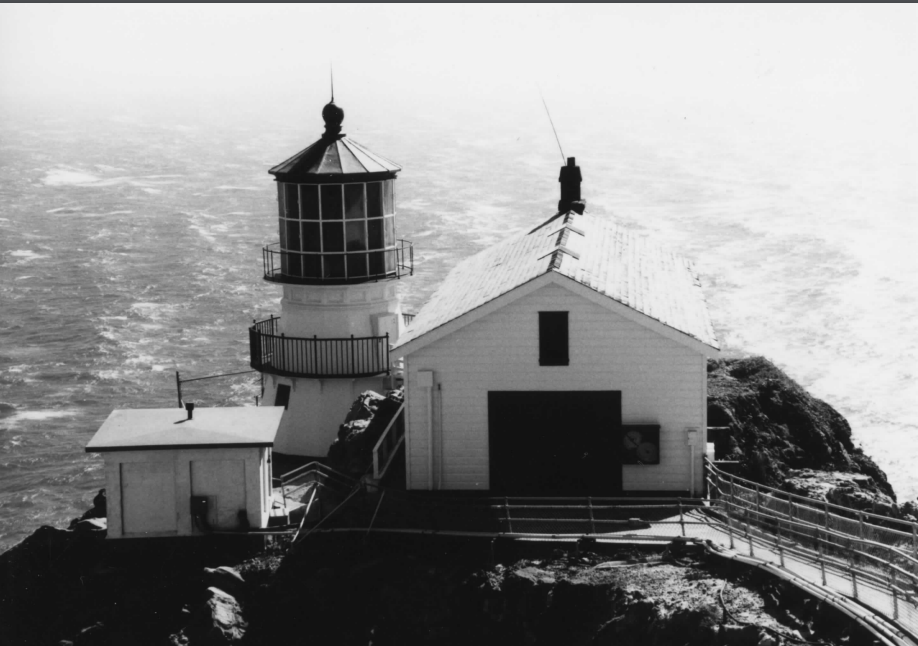

All lighthouses serve as navigational signposts for pilots of ships, both at sea and on inland waterways, but the lighthouse at Port Reyes, California, is an example of extreme civil engineering. Built to protect ships navigating San Francisco harbor, the lighthouse stands on Point Reyes, above the headlands that jut out ten miles into the sea and thus threaten ships moving between San Francisco Bay and points north. Point Reyes is the windiest and foggiest spot on the West Coast—it is often completely obscured by fog, and the wind routinely blows forty miles per hour and sometimes gusts up to one hundred miles per hour there.

Point Reyes in CA

National Archives Identifier: 45709193

Although Congress authorized funds to build a lighthouse on Point Reyes in 1854, local opposition stalled the project for more than fifteen years, during which time seventeen shipwrecks occurred there. Construction finally began in 1870. Materials had to be transported by wagon over steep hills to the headland above sea. Two terraces were then cut into the mountain below, one for the fog signal one hundred feet above the sea and one 240 feet above the sea for the lighthouse. Built of forged-steel plate, the sixteen-sided tower is bolted to solid rock. The lantern is thirty-seven feet above the ground, reachable by 308 steps that lead down from the family quarters above it. The focal plane of the light is 294 feet above sea level. The quarters, which were built in 1960, could accommodate four men.

Point Reyes keeper’s house

The Point Reyes Light Station was retired from service in 1970. The National Park Service now maintains the property, which is open to the public.

Point Reyes in the National Register of Historic Places

National Archives Identifier: 123857643

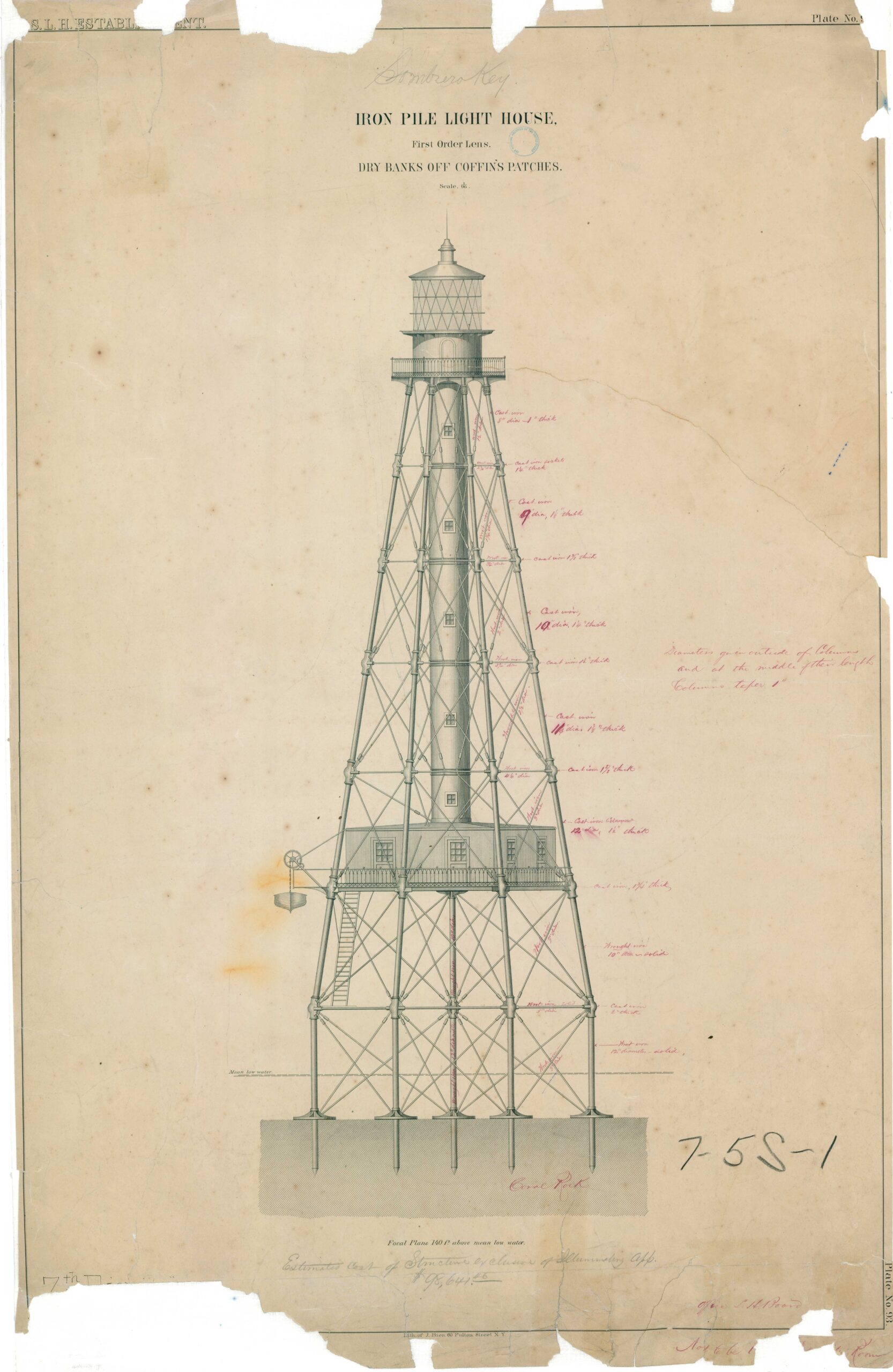

General Contractor

General George Gordon Meade is best known for his actions during the Civil War. He commanded the Army of the Potomac from 1863 to 1865 and was largely responsible for the victories of Union troops at the battles of Fredericksburg and Gettysburg, although President Abraham Lincoln criticized Meade for not pursuing Robert E. Lee as he retreated after that battle ended. Lincoln appointed General Ulysses S. Grant general-in-chief in March 1864, prompting Meade to offer to resign. Grant refused to accept Meade’s resignation, but Grant made all the key decisions about the Union troops’ movements for the duration of the war. Meade was responsible for carrying those orders out.

Meade’s life and career before the war are less well-known. He was born on New Year’s Eve in 1815 in Cádiz, Spain. His father, Richard Worsam Meade, had made a fortune by trading with Spain, but he was ruined by the Peninsular War and was forced to bring his wife, Margaret Coats Butler, and their children back from Spain to his ancestral home in Philadelphia in 1817. George was the eighth of eleven children. Richard Worsam Meade died in 1828.

George Meade went to school at the American Classical and Military Lyceum in Philadelphia and the Mount Hope Institution in Baltimore before he entered the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1831. He only served in the military until 1836, resigning his commission to pursue his true passion—civil engineering. From then until 1842, he worked for the Alabama, Georgia, and Florida Railroad and the War Department. He married Margaretta Sergeant on his birthday in 1840.

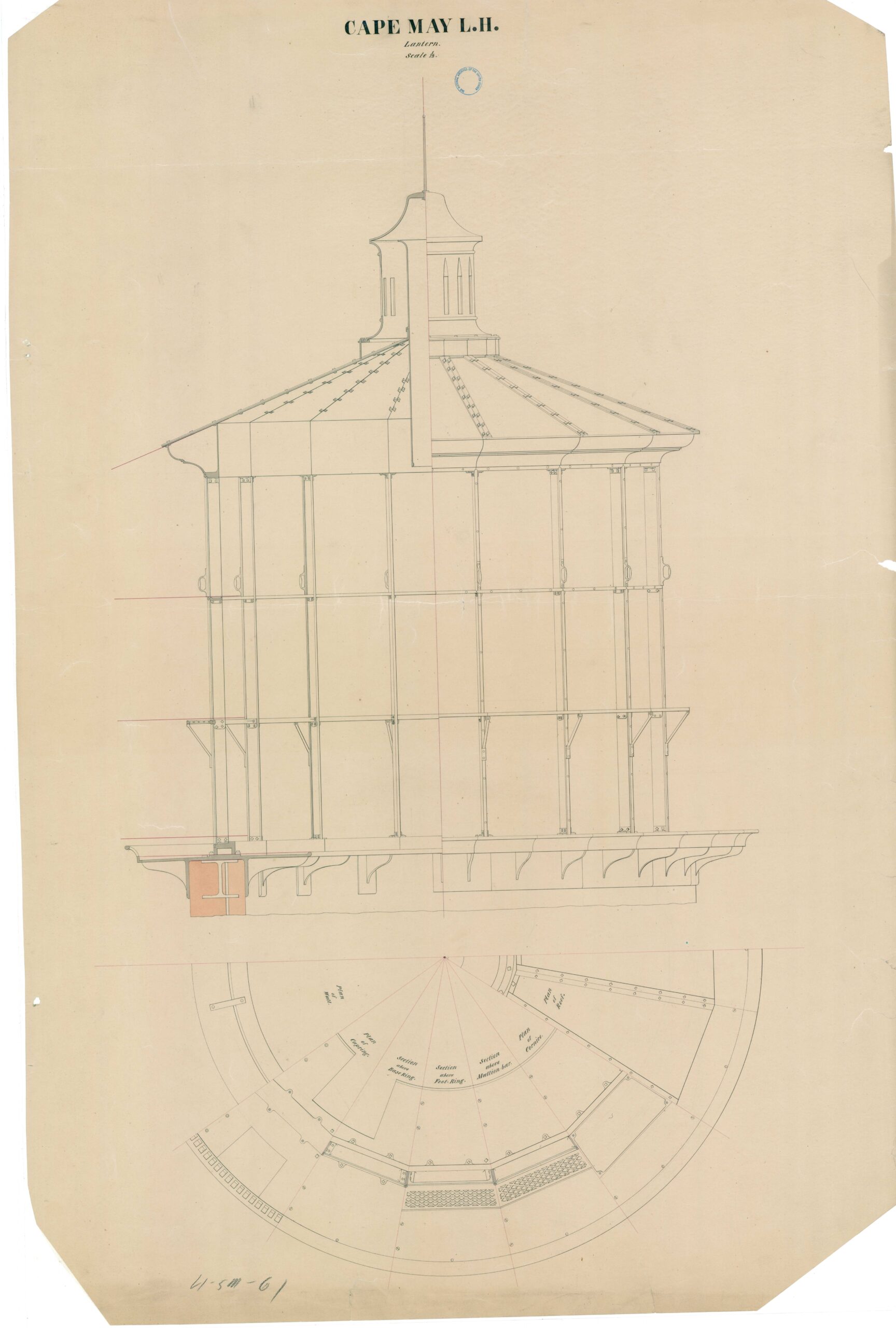

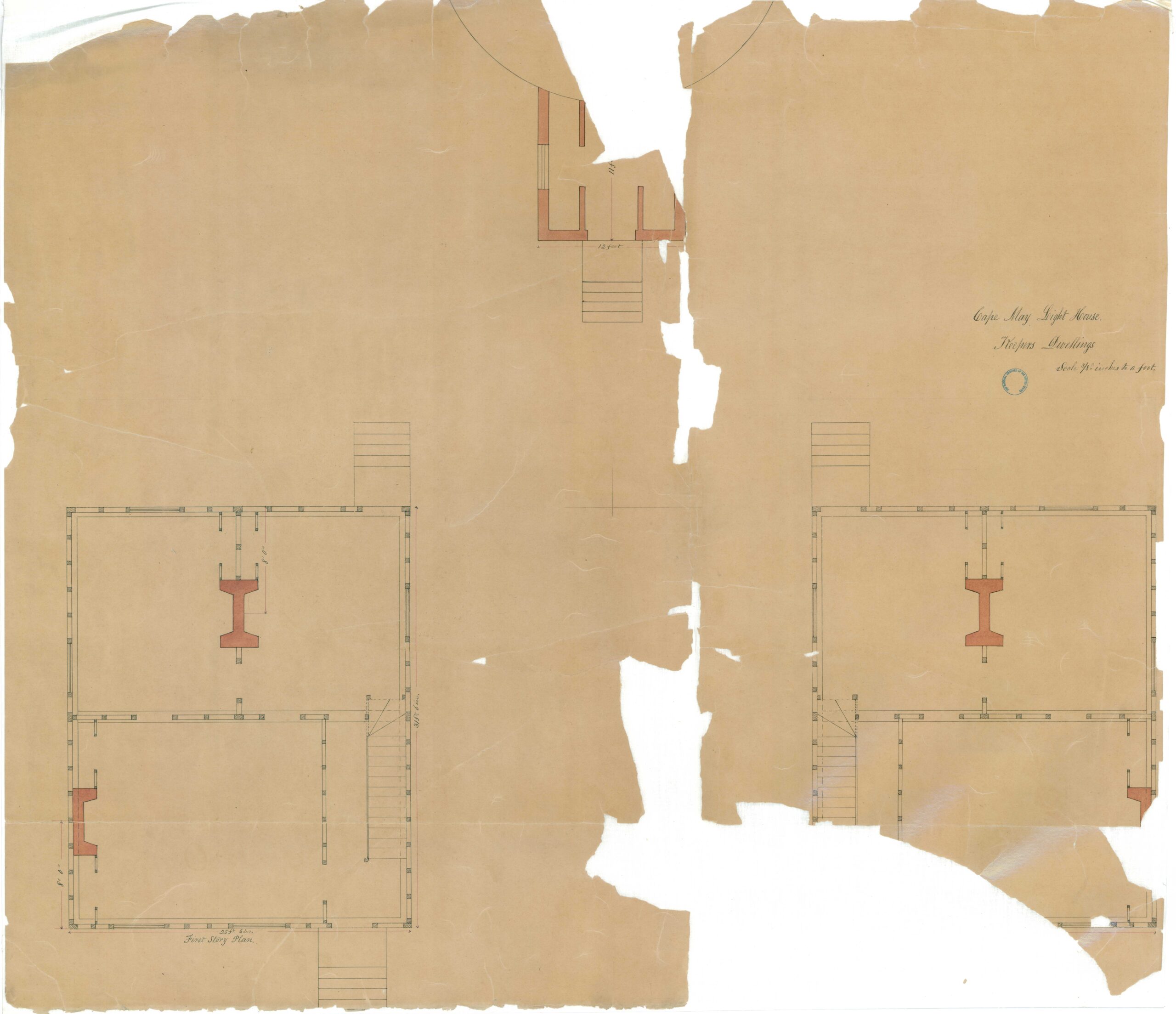

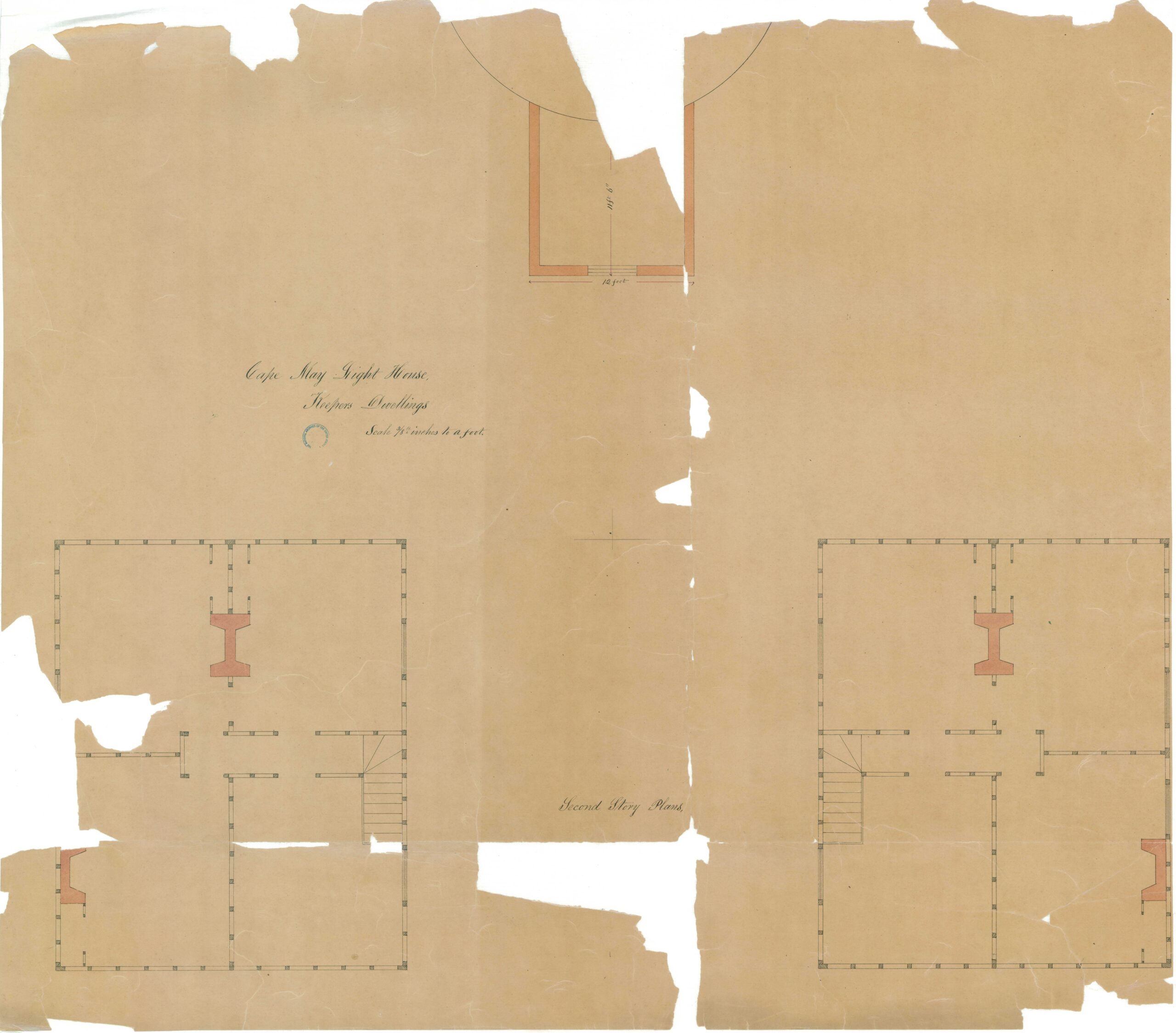

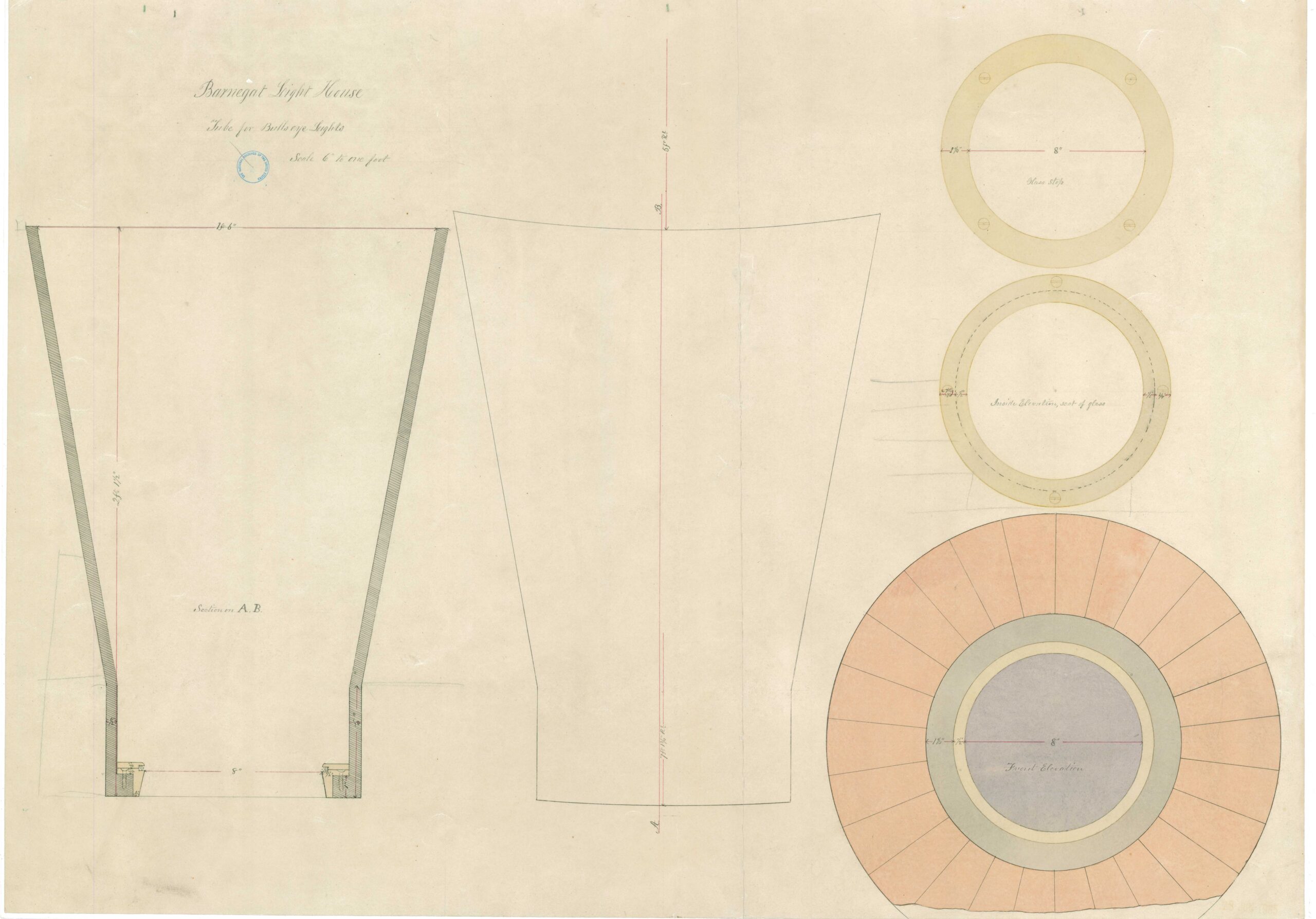

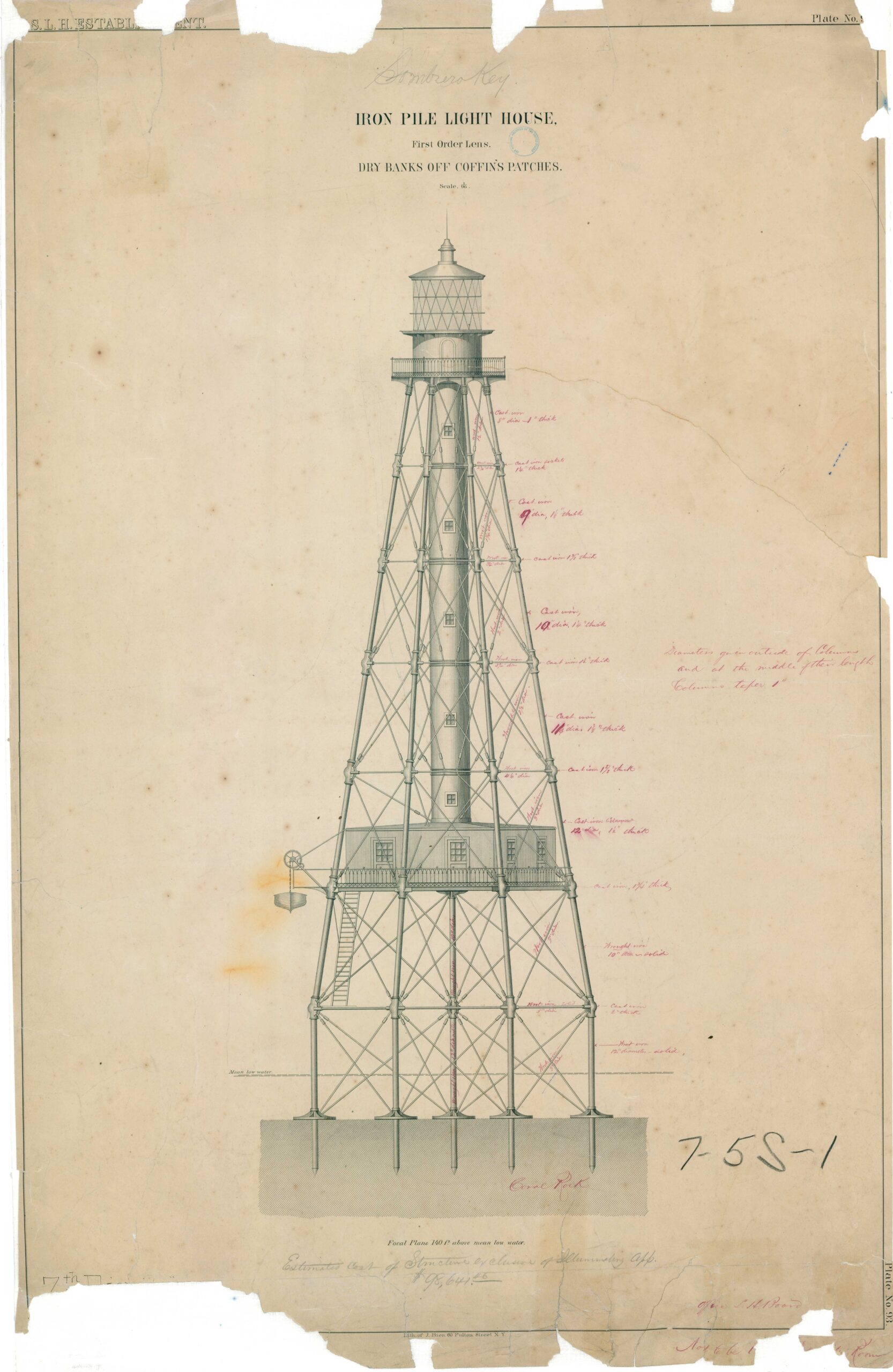

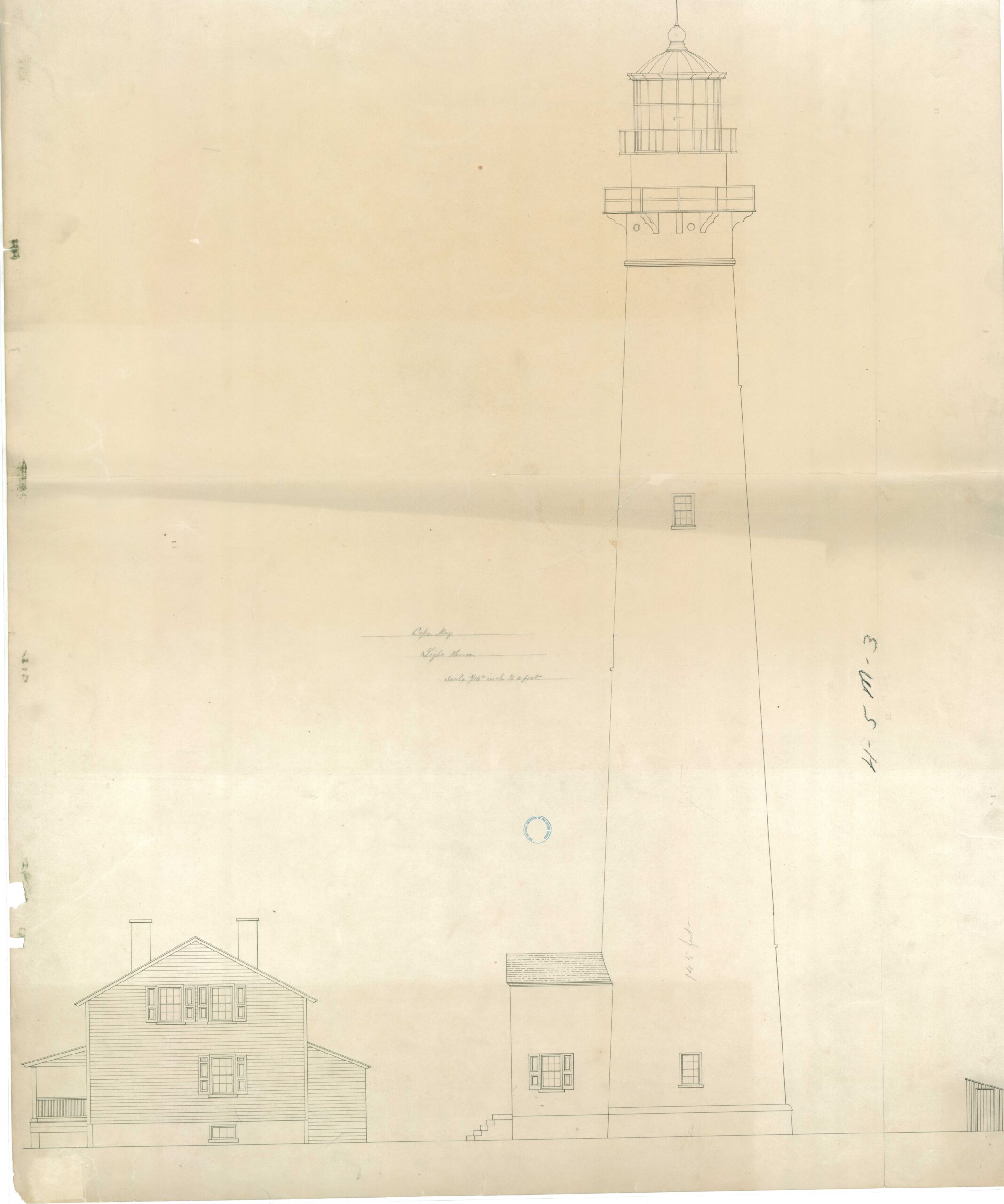

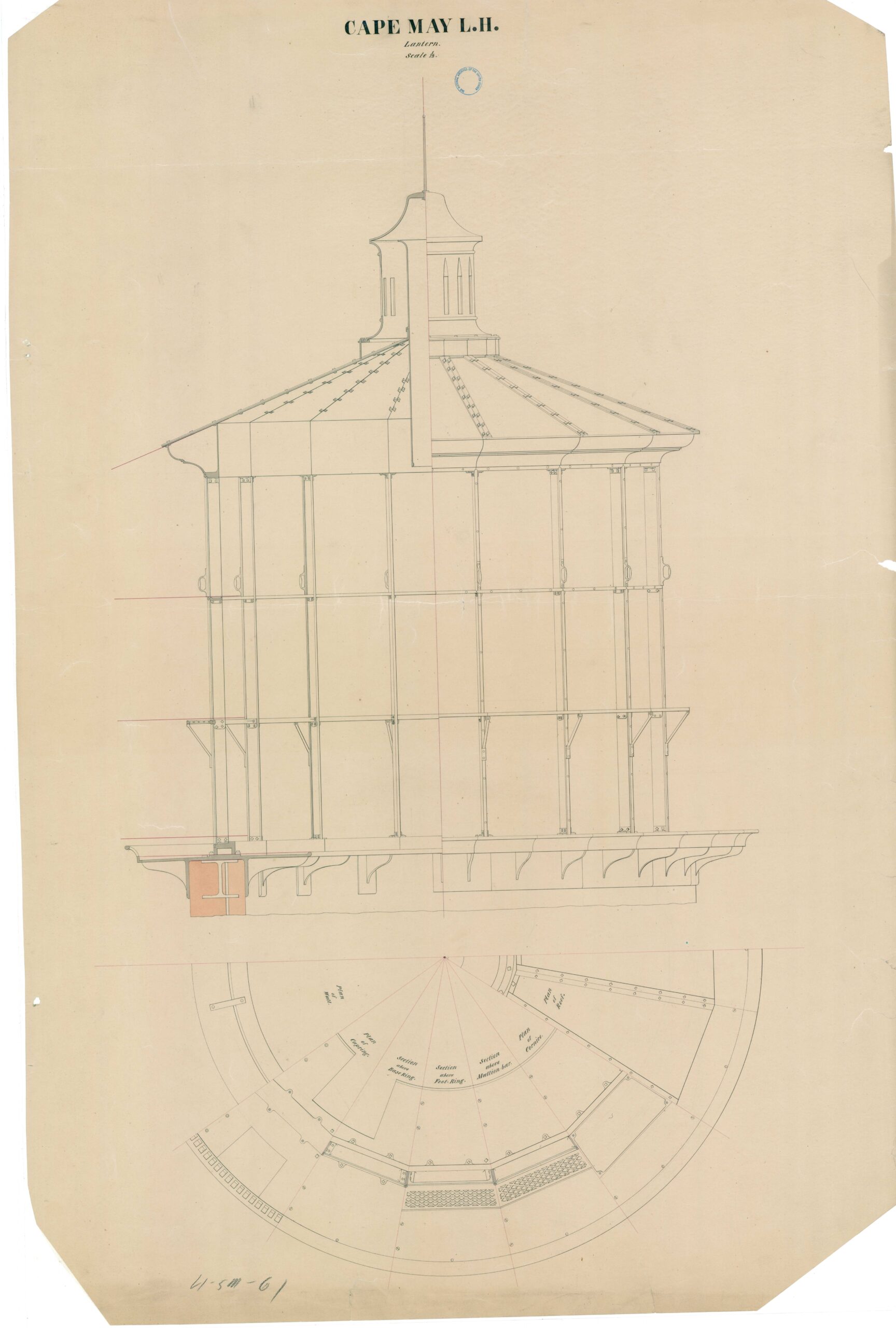

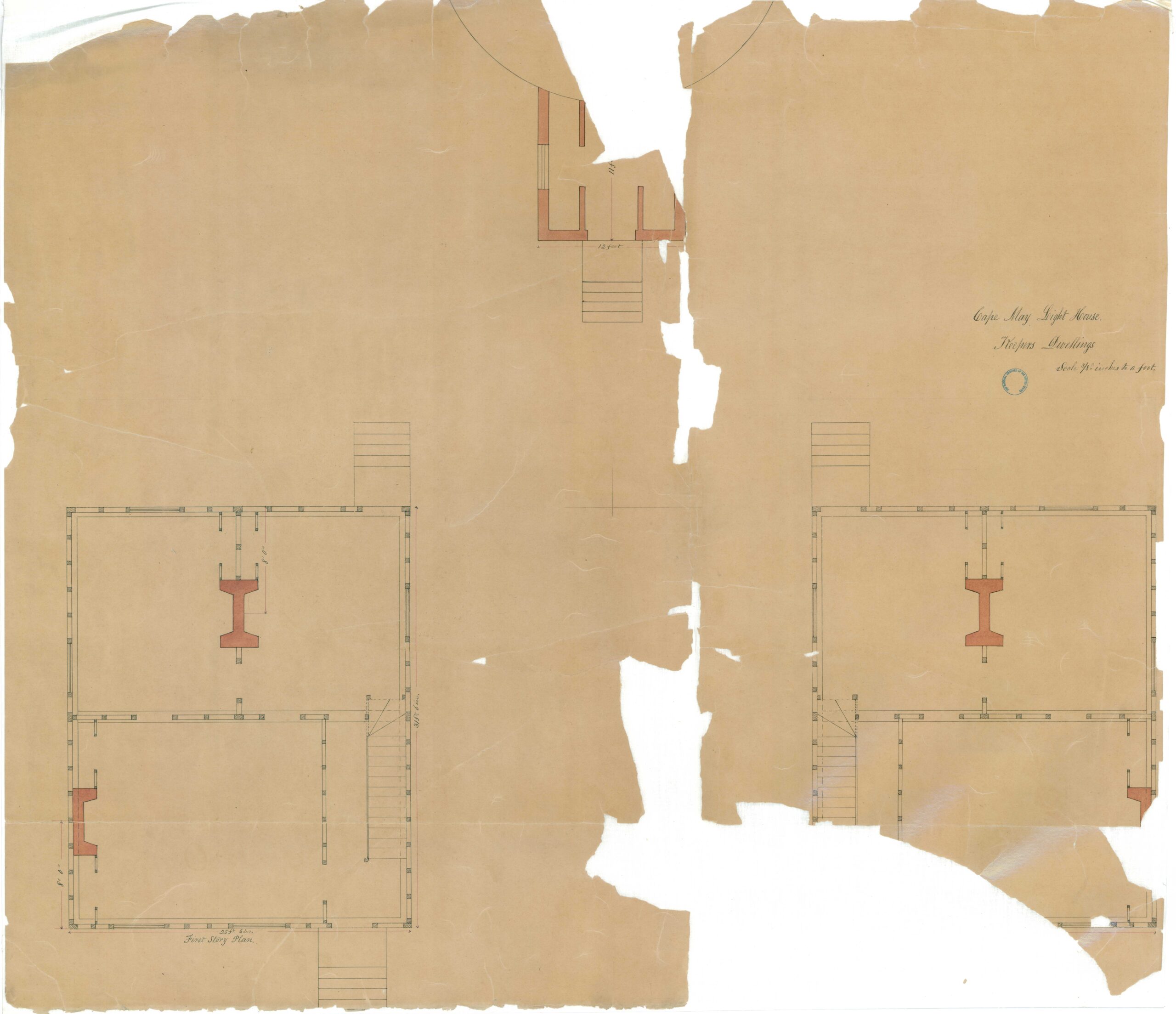

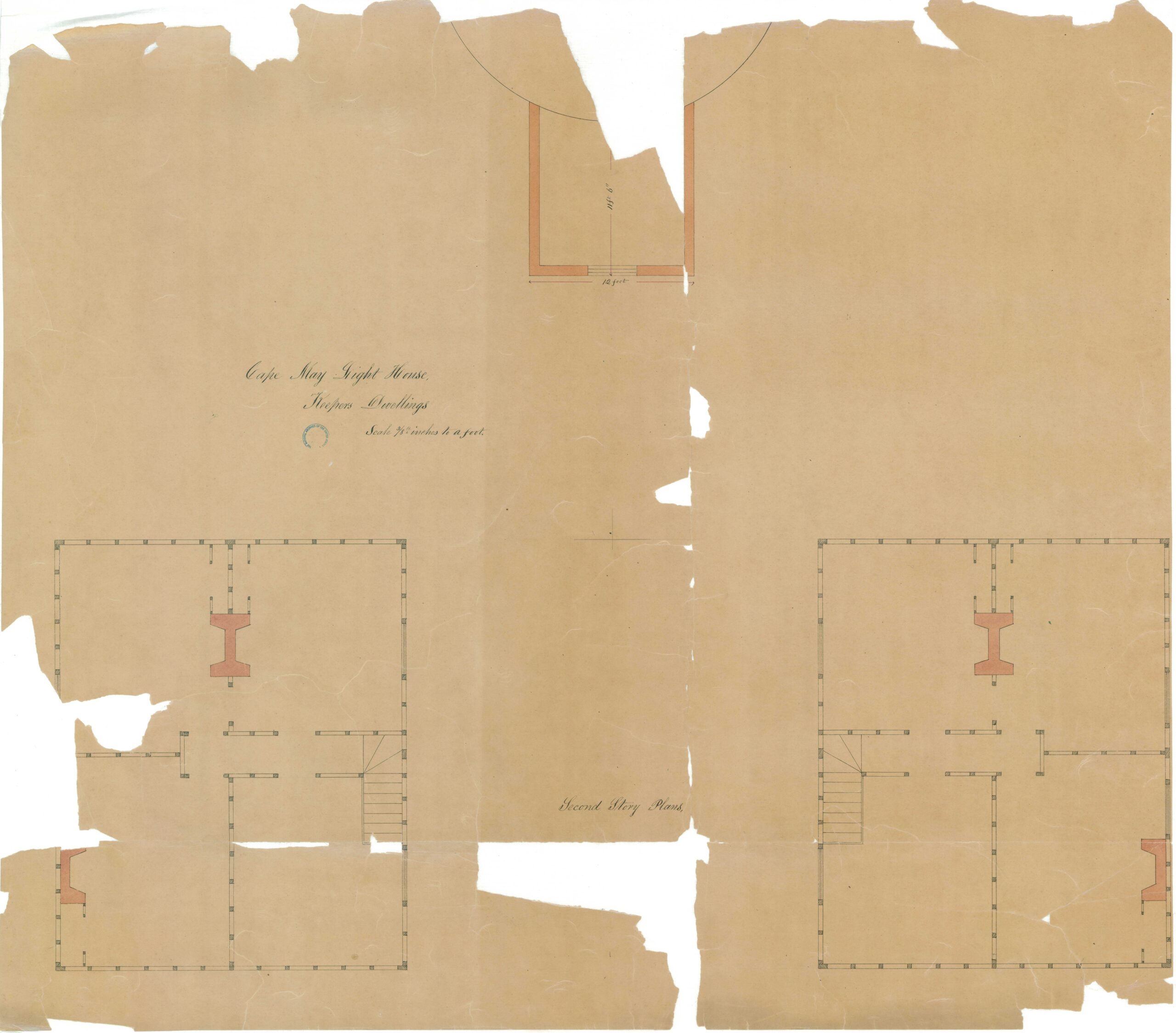

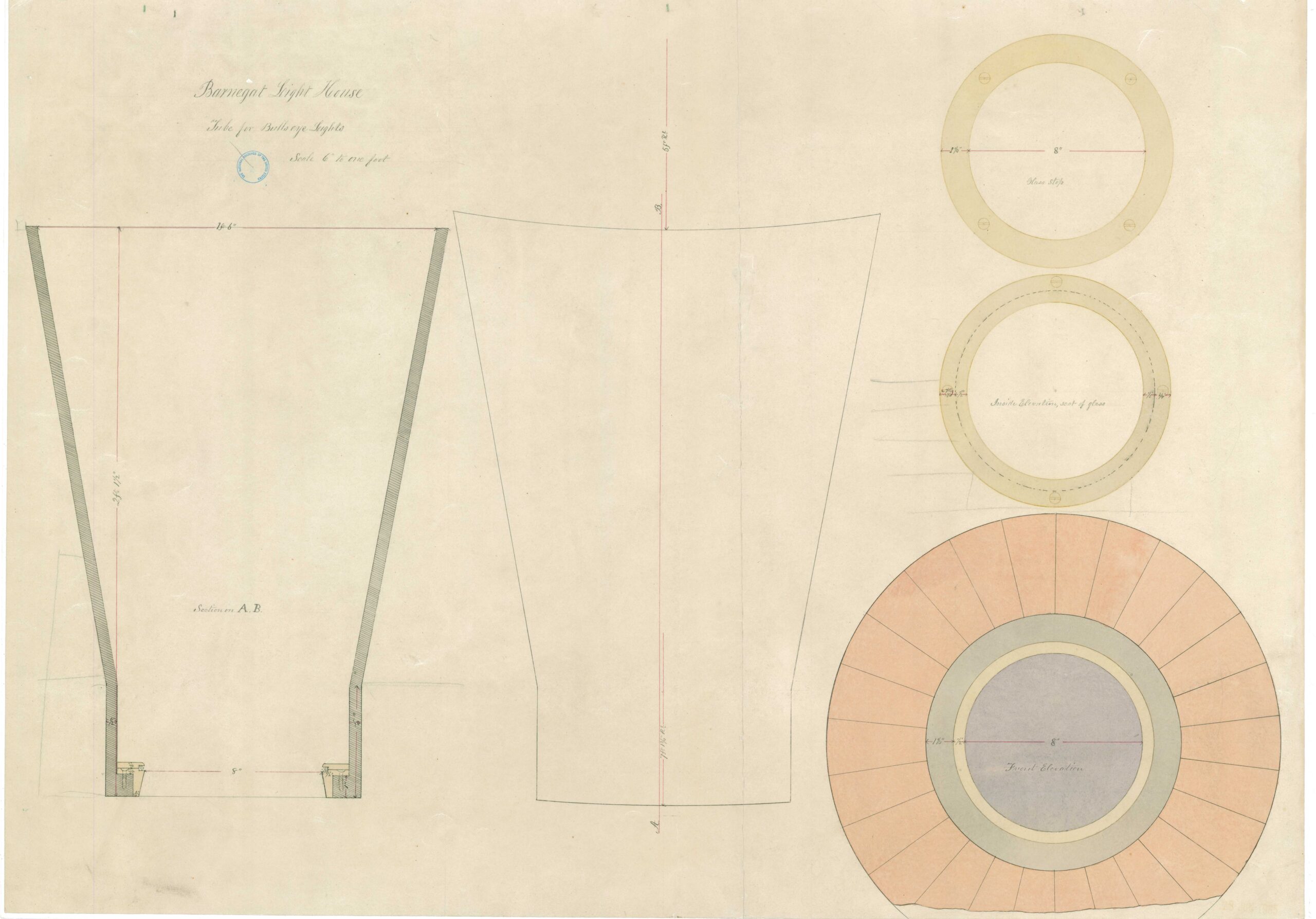

Meade reenlisted in 1842 and served with distinction in the U.S.-Mexican War under the commands of Generals Zachary Taylor, William J. Worth, and Robert Patterson. He then returned to civil engineering, designing lighthouses and breakwaters and conducting coastal surveys in Florida and New Jersey. He designed five very important lighthouses—Barnegat Light on Long Beach Island, New Jersey; Absecon Light in Atlantic City, New Jersey; Cape May Light in Cape May, New Jersey; Jupiter Inlet Light in Jupiter, Florida; and Sombrero Key Light in the Florida Keys. Meade also designed a hydraulic lamp that the Lighthouse Board adopted for use in American lighthouses. Meade’s personality was often described as “prickly”—perhaps the solitary but dutiful nature of lighthouses appealed to him.

George Gordon Meade was very seriously wounded at the Battle of Glendale in Henrico County, Virginia, on June 30, 1862, but he continued to serve the Union for the duration of the Civil War. He died on November 6, 1872, of pneumonia, which was most likely a complication of his war wounds.

To view the text of a document or the full image, click on the image displayed above

Eerie Sightings

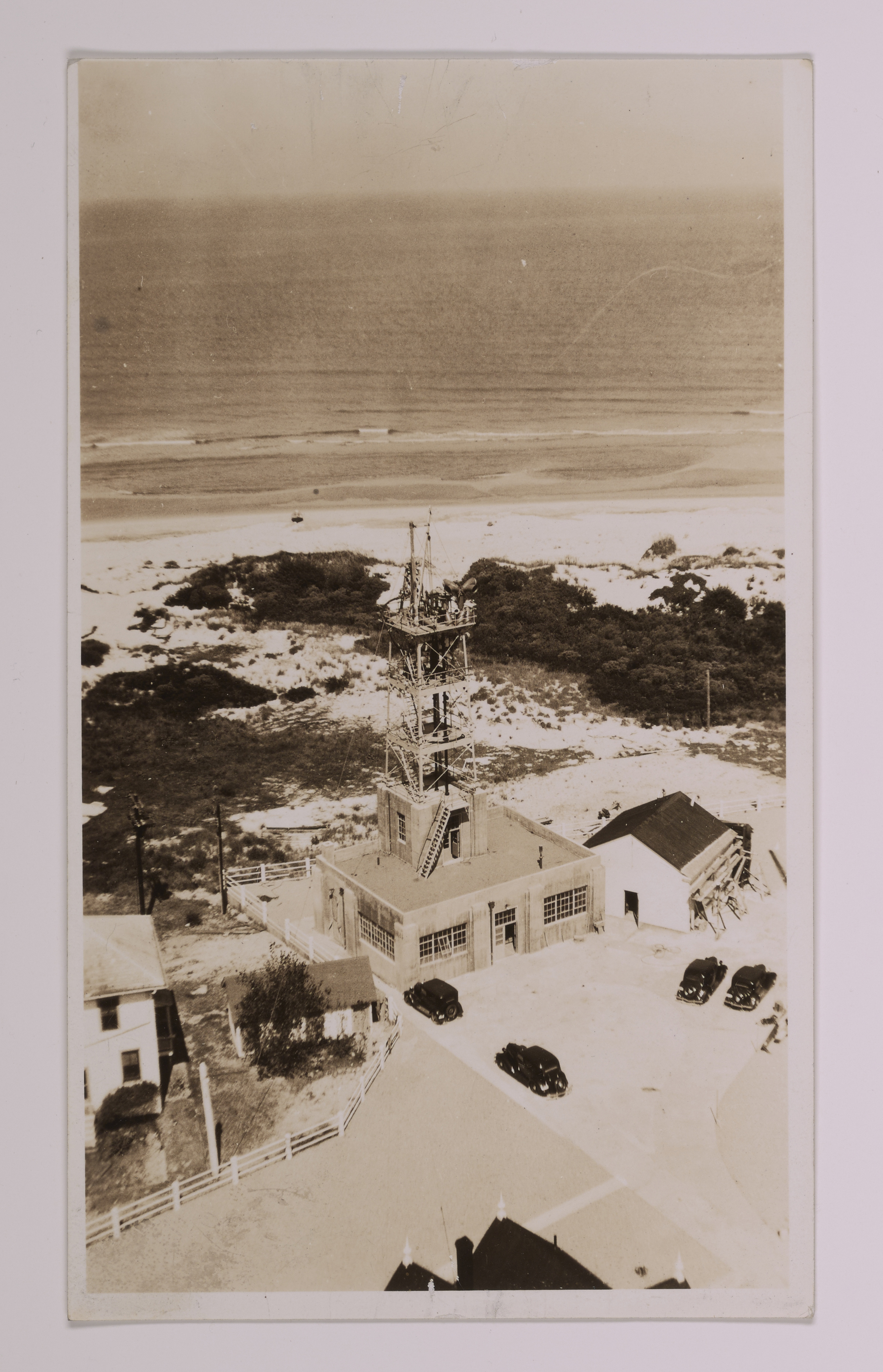

Point Lookout station and depot

National Archives Identifier: 7682779

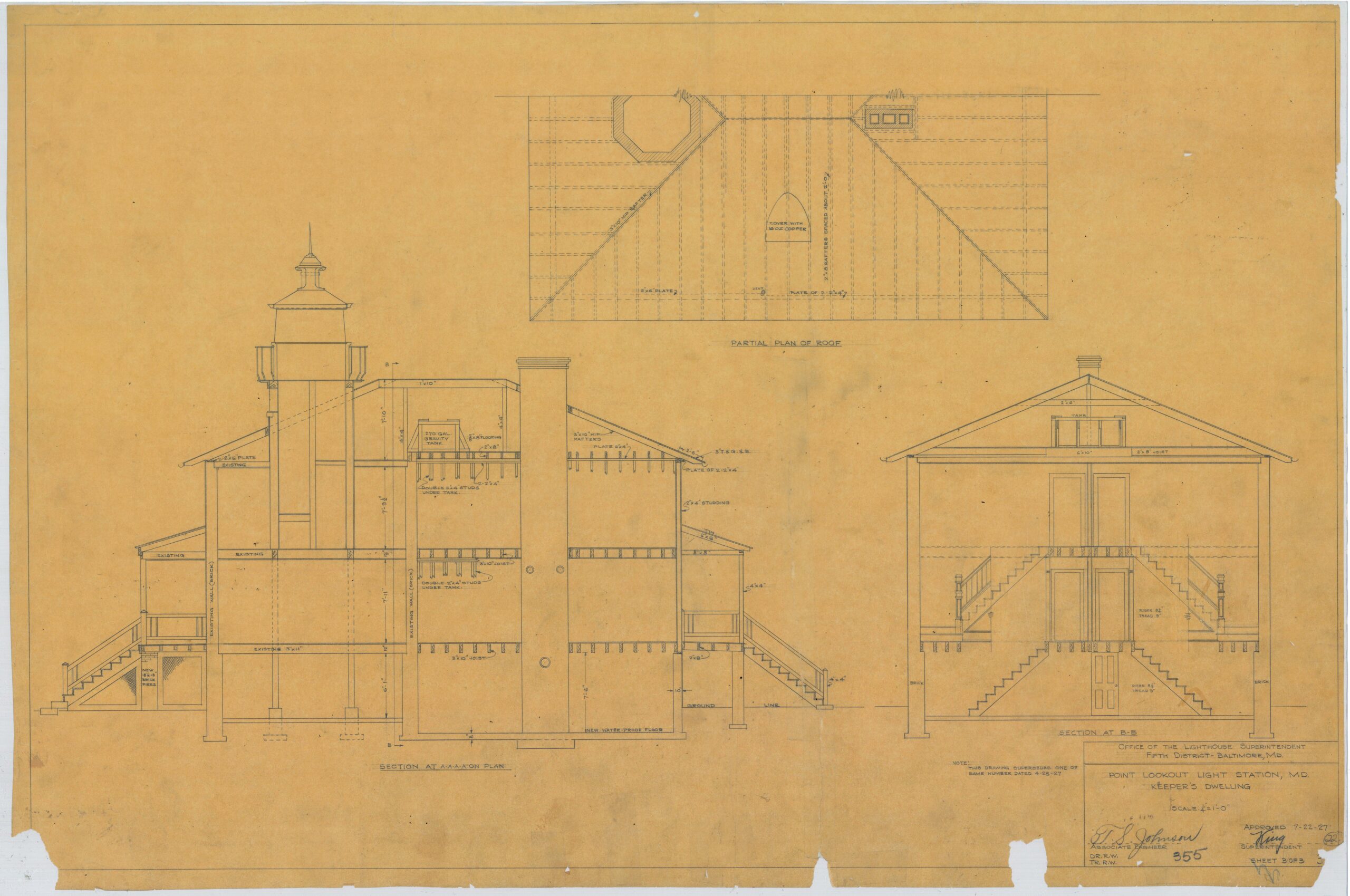

Point Lookout Light stands at the very southernmost tip of St. Mary’s County, Maryland, where the Potomac River empties into Chesapeake Bay. Authorized by Congress in 1825, the lighthouse’s construction was delayed by wrangling with local property owners until 1830, when it finally became operational on September 20. The first keeper, James Davis, died just a few months after he assumed the job, but his daughter maintained the lighthouse until 1847.

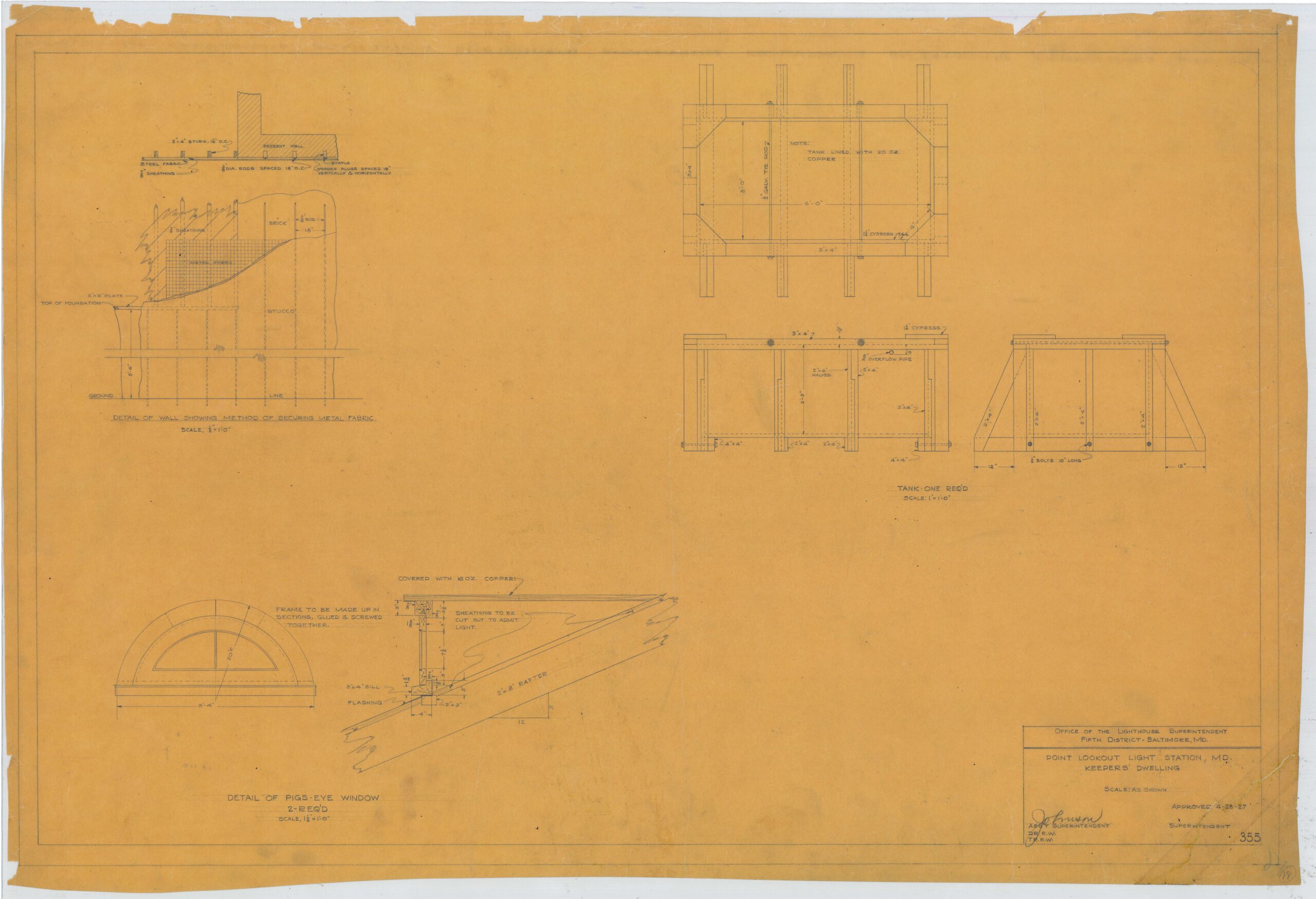

Keeper’s dwelling at Point Lookout

National Archives Identifier: 148952632

The Point Lookout Light has gained the reputation of being the most haunted lighthouse in the country, mostly because after the Battle of Gettysburg, the federal government turned the 530-acre site into a Union prisoner-of-war camp. Originally built to house no more than 10,000 prisoners, the twenty-acre enclosure eventually held 20,000. Epidemics of diseases were rampant, food was scarce, and supplies of medicines and clothing were nonexistent—in short, conditions were dire. By the end of the war, at least 3,000 prisoners had died there.

Many people who have visited the lighthouse report having seen or felt the presence of spirits, especially those of soldiers who have been seen wandering aimlessly around the area. When the steamer Express sank off Point Lookout in October 1878, one of its officers, Joseph Haney, drowned trying to row ashore for help. He is rumored to have been seen on the beaches of Point Lookout.

Keeper’s dwelling at Point Lookout

National Archives Identifier: 148952662

People who have lived at the lighthouse have reported hearing strange noises in their living quarters at all hours and seeing books and other objects flying off their shelves. One paranormal investigative team recorded more than twenty-four different voices, both male and female. Chilly spots and rotten smells were observed, and during one seance in the 1970s, photographic evidence of two different spirits were recorded.

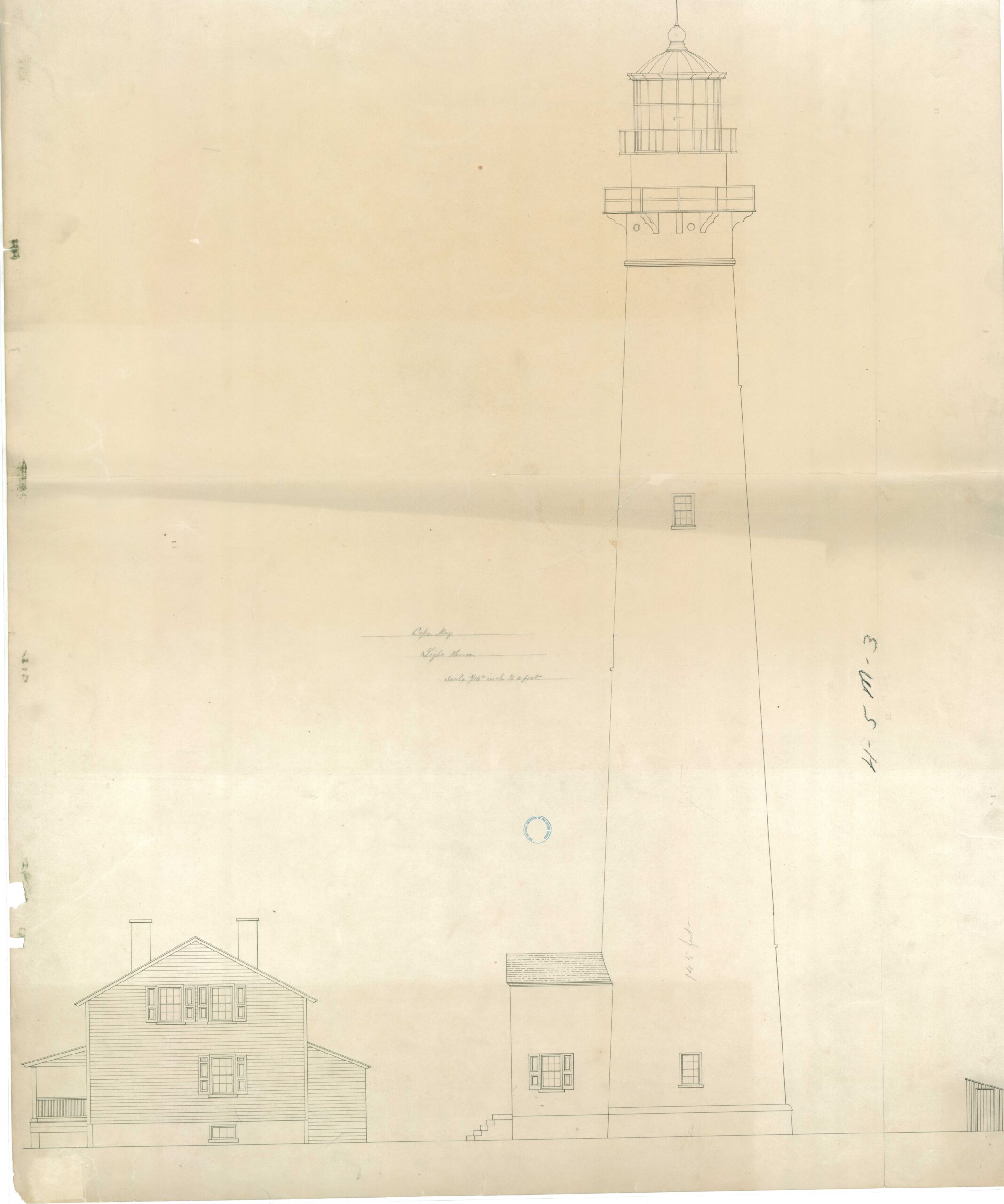

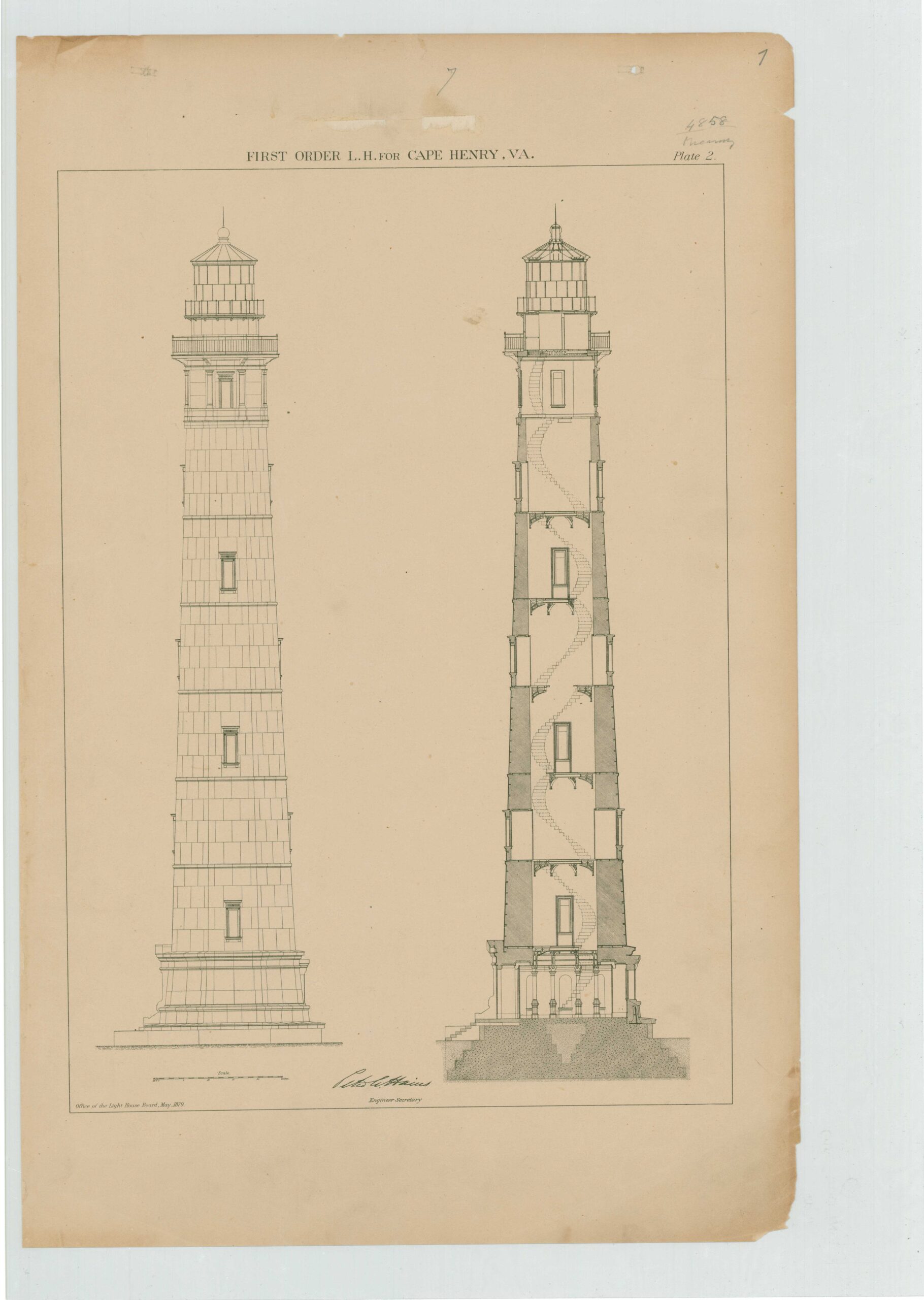

The Early Light

The first lighthouse built on Cape Henry, at the southern entrance to Chesapeake Bay in Virginia, was the very first federal construction project authorized under the U.S. Constitution. The architect, John McComb, Jr., also helped design New York City Hall and other lighthouses on the East Coast. The sandstone Cape Henry Lighthouse was completed in October 1792.

A second lighthouse was built 350 feet northeast of the older tower in 1881 due to concerns about its condition. In 1970, the two together were designated a National Historic Landmark.

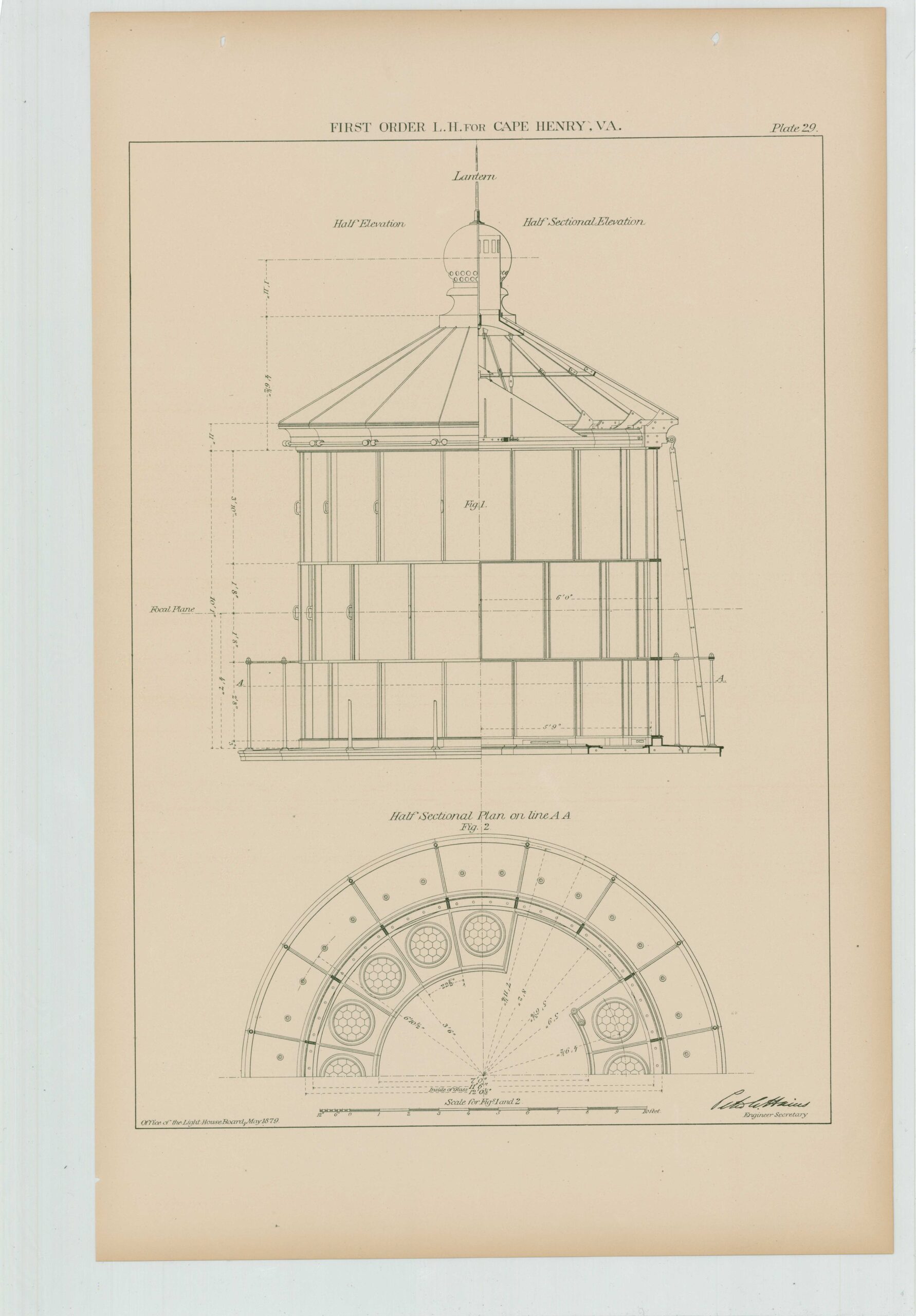

Cape Henry Light in VA National Archives Identifier: 45693933 |

Cape Henry lantern National Archives Identifier: 87201837 |

Cape Henry elevation plan National Archives Identifier: 87201809 |

A Daring Rescue

Cape Elizabeth Light on the southwest entrance to Casco Bay in Maine is also known as Two Lights because originally, two lighthouse towers of rubble stone were built there 300 feet apart in 1828. The first steam-driven whistle in North America was installed in a fog signal station near the towers in 1869. The towers were replaced with two sixty-seven-foot-high cast-iron lighthouses that stood 129 feet above the sea in 1874.

The perilous navigational conditions there still resulted in many shipwrecks. In January 1885, the lighthouse keeper, Marcus A. Hanna, a Civil War veteran, saw the schooner Australia wreck on the rocks below the lighthouse in a violent blizzard. He rescued the two sailors who were aboard the ship and brought them to safety in the lighthouse. For his bravery, Hanna received the Gold Lifesaving Medal from the United States Coast Guard in April 1885. Hanna also received the Congressional Medal of Honor in 1895 for his actions during the Civil War, making him the only person in American history to receive both awards.

Two Lights at Cape Elizabeth Maine National Archives Identifier: 18237395 |

Gold life saving medal National Archives Identifier: 205583341 |

Cape Elizabeth Maine National Archives Identifier: 18237445 |

Two Lights from the National Register of Historic Places

National Archives Identifier: 88685906