One by One: Evolving Women’s Rights

The 19th Amendment officially became law on August 18, 1920, just over 104 years ago today. While it helped some achieve suffrage, namely white women of means, it did not automatically enfranchise all women. That said, women dating back to the founding of the U.S. fought, and continue to fight, for other rights in various aspects of their lives. Let’s examine a select few instances of these other rights—the right to divorce, work, and manage their own finances—and how they underscore women’s ongoing struggle for full control of their livelihoods.

Right to Divorce

The Seneca Falls Convention of 1848 spotlighted many contemporary women’s issues, including the difficulty of obtaining a divorce. At that time, divorce laws were fault-based, requiring proof of specific grounds such as adultery or cruelty to proceed. Because filing for divorce was burdensome, if not just outright costly, some women had to stay in unhappy marriages. The Declaration of Sentiments, the seminal document written at the convention, criticized these laws for being skewed in favor of men.

The Declaration of Sentiments, 1848

National Archives Identifier: 75316068 page 87

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who eventually became a suffrage leader, advocated for easier divorce processes. Some convention attendees feared that pushing for divorce reform would link the movement to the controversial “free love” ideology, which challenged traditional marriage norms. Instead, suffrage was embraced as a more palatable issue for the women’s rights movement at the time.

Statue in the U.S. Capitol Building depicting three prominent suffrage leaders. From left to right: Lucretia Mott, Susan B. Anthony, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton

National Archives Identifier: 7718581

Individual states set their own rules on divorce, which caused issues between them. Some states, like Indiana, were considered divorce mills in the late 19th century because they had relatively lax standards for divorces, resulting in hundreds of couples crossing state lines to avoid their home state’s divorce laws.

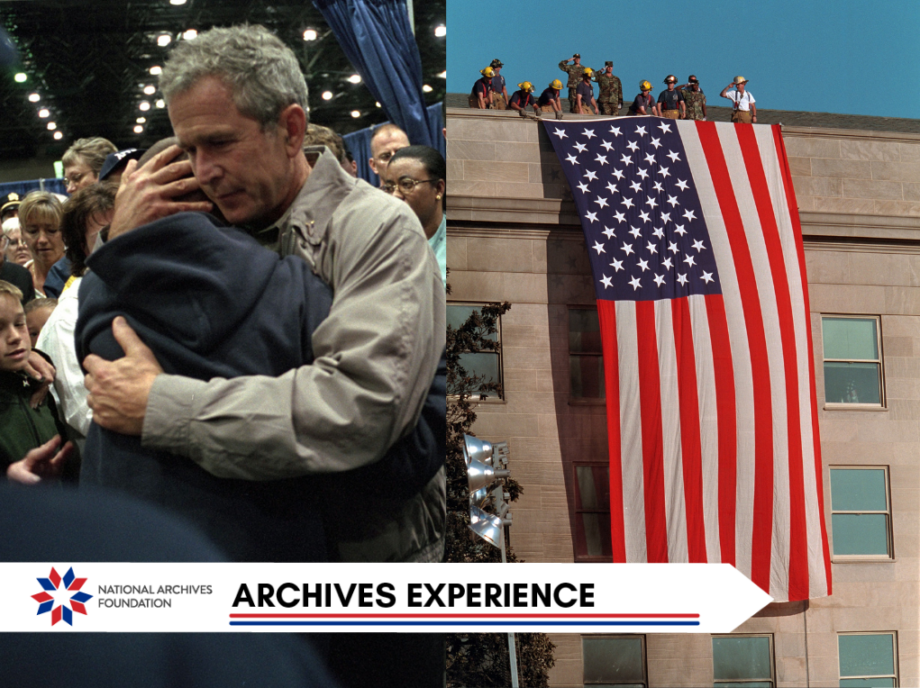

Divorce laws evolved toward no-fault systems, allowing couples to separate without proving wrongdoing. In fact, then-Governor Ronald Reagan was the first to sign a statewide no-fault divorce statute into law in California in 1969. This shift, influenced by early women’s rights activists, represents a significant change from the fault-based systems of the past.

Newly elected Governor Ronald Reagan and wife Nancy Reagan

celebrate election night victory, 1966

National Archives Identifier: 75857147

Right to Work

World War II was another milestone moment for women’s rights. With millions of men enlisted in the military, industries crucial to the war effort, such as manufacturing and shipbuilding, faced labor shortages. Women stepped in to fill these gaps, taking on roles men traditionally occupied.

Two African American women riveters, 1941–1945

National Archives Identifier: 535811

Women Operating Sawmill, 1942

National Archives Identifier: 89570453

After World War II, women who had taken on industrial and clerical jobs faced pressure to relinquish their positions to returning male veterans, often being sent back to the home and away from work altogether. For a large share of non-White women, this was not the case because they disproportionately worked in domestic-adjacent roles such as cleaning and caretaking.

Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, the section on employment, is the only part of the act that explicitly prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex. In fact, the addition of the word “sex” was added by an anti-civil rights legislator as an attempt to thwart the bill altogether.

President Lyndon B. Johnson signing the Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law, 1964

Source: Lyndon B. Johnson Library

While the inclusion of “sex” was a political calculation, the effects of Title VII reverberated across the country for working women. Title VII became the center of much case law surrounding employment discrimination and is the reason that workplace sexual harassment and a “hostile work environment” is now illegal.

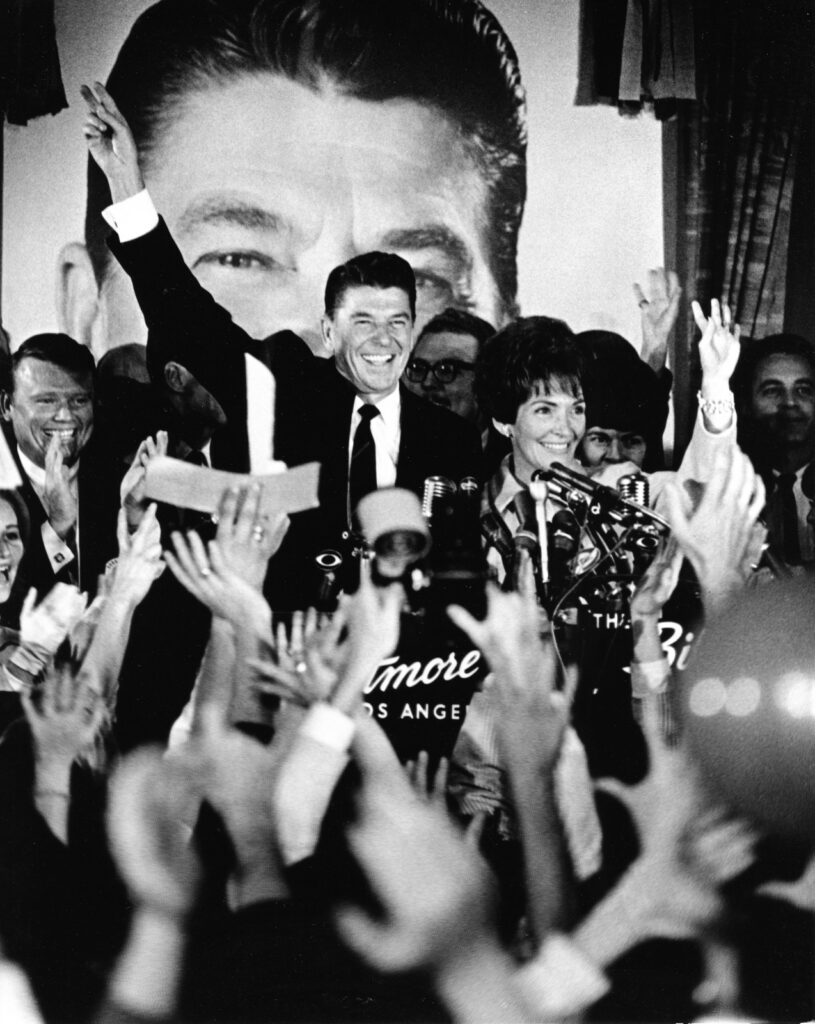

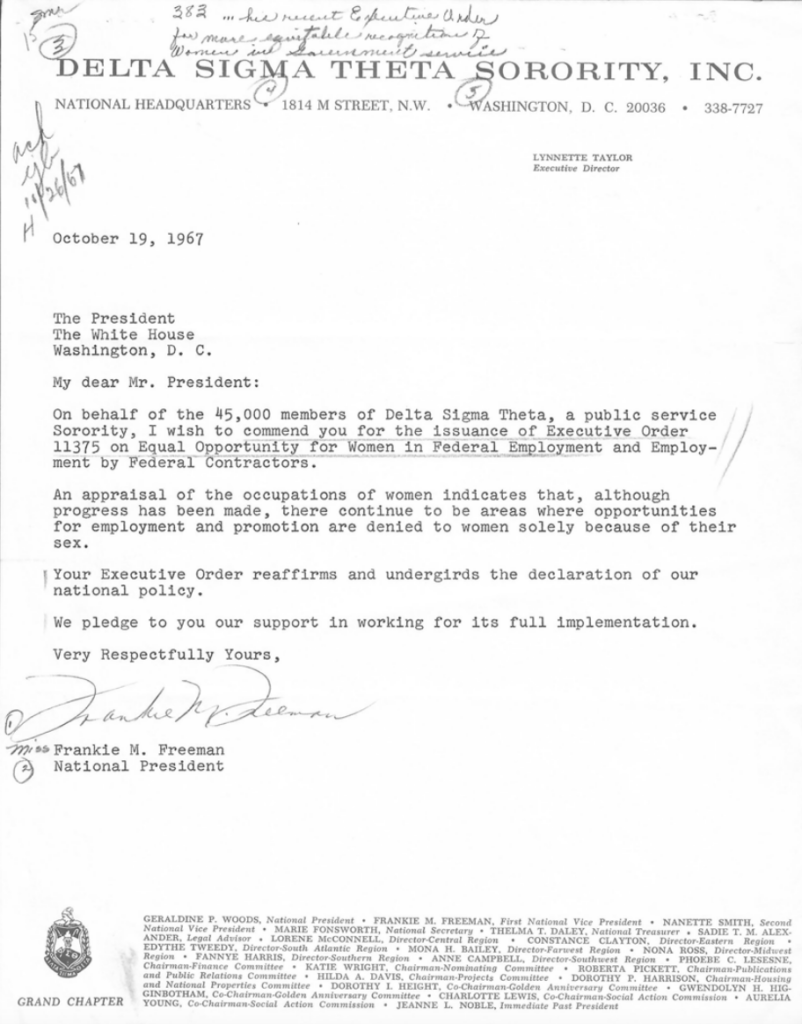

Frankie Freeman, a Johnson appointee, expressed her appreciation as president of the black women’s service sorority Delta Sigma Theta for the explicit addition of women to those protected from bias in employment, 1967

National Archives Identifier: 133876152

Right to Manage Finances

As more women entered the workforce,they often faced obstacles to managing their own finances, including being unable to hold or extend lines of credit. That all changed with the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA) Amendments and the Consumer Leasing Act of 1974.

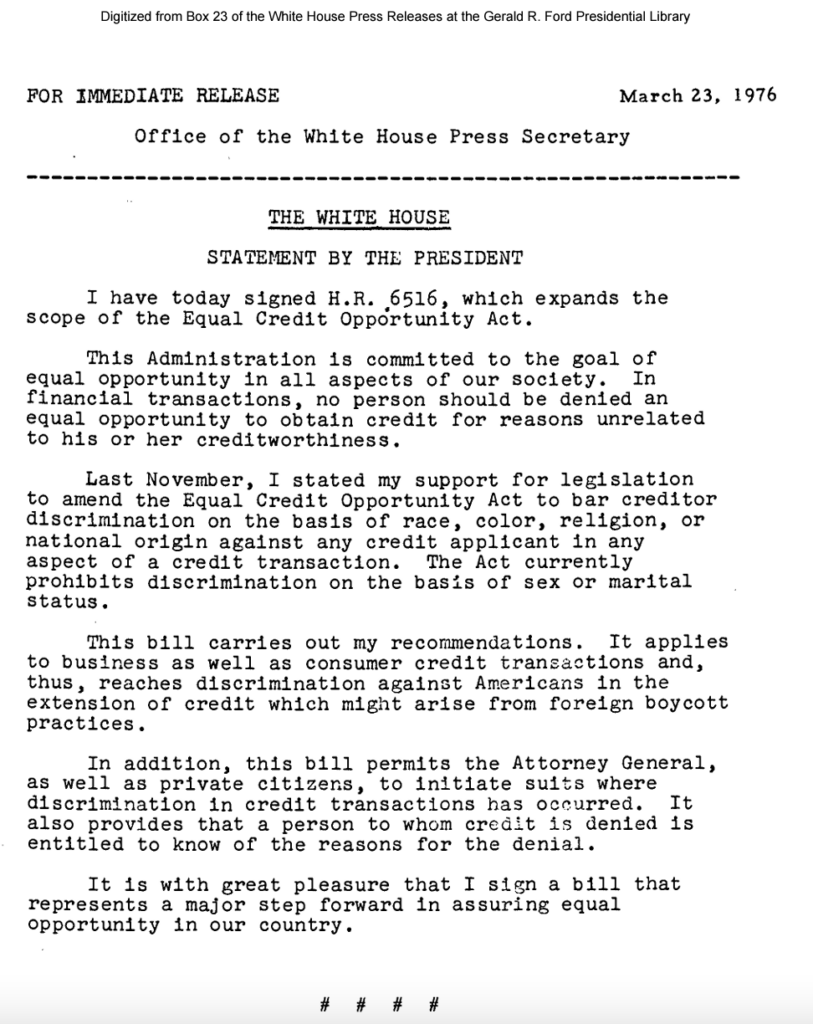

President Ford’s Press Release announcing the signage of the

Equal Credit Opportunity Act Amendments into law, 1976

National Archives Identifier: 7343168

Prior to this act, states barred many women from opening and operating their own lines of credit or loans without a male cosigner. In the 19th century, women were bound by coverture, the legal doctrine that treated women as dependent rather than independent financial entities. While women gained more independence into the 20th century, this norm persisted. The ECOA aimed to address these discriminatory practices and ensure equal access to credit for all individuals.

After grassroots pressure in the 1970s, Congress put the law into place, preventing financial institutions from discriminating against a financial borrower on the basis of sex or marital status.

President Ford signing the the Equal Credit Opportunity Act Amendments into law, 1976

Source: NARA’s Pieces of History blog

The attainment of rights by and for women demonstrates one aspect of our democracy at work. You can learn more about women’s rights projects as well as other struggles for freedom in the Records of Rights exhibition in the David M. Rubenstein Gallery. You can also explore the online experience here.

Related Content

Progress at the Ballot Box: 60 Years of the Voting Rights Act

Marching into History: The Women’s Army Corps