The People, United

Welcome to the Archives Experience debut series: A Republic, If You Can Keep It. In celebration of Constitution Day, we’re chronicling the creation of this document—but these aren’t the stories we’ve all heard before. Instead, we’ll look at how the National Archives holdings show just how close we came to an entirely different form of government and how “We the People” triumphed in the end.

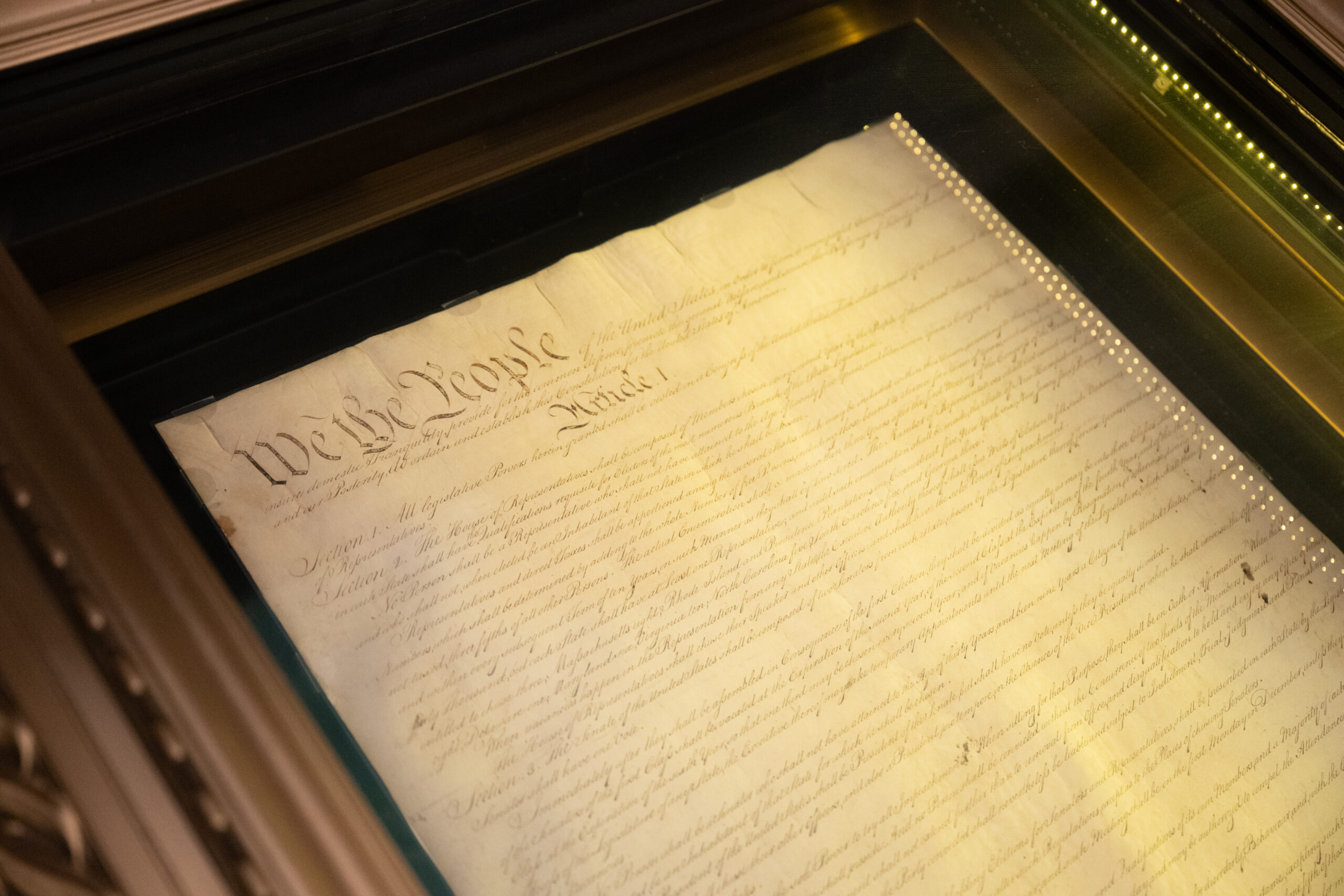

Language matters, and nowhere is that more true than in the text of our founding documents. Tension around the fundamentals of our government has arisen because of a singular word or even the placement of commas. So imagine the stress of writing a preamble to an entirely new constitution.

That was the task of the Founding Fathers in September of 1787, days before the Constitution was signed. And after the division sewn by the Articles of Confederation, the Founders almost left the Constitutional Convention without the document’s iconic opening words…

History Snack

A new era of leadership at the National Archives…

The Constitution has been the foundation of government in the United States for 235 years. Throughout more than two centuries, a devastating civil war, two world wars and innumerable lesser conflicts, and massive social upheavals, it has proven clear, authoritative, and sufficiently flexible to guide the growing nation.

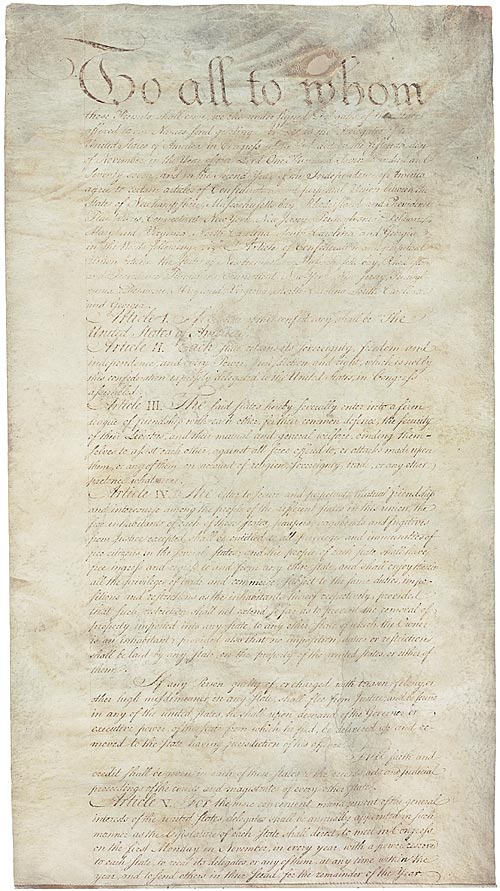

But it is important to remember that the first document to which the states tied their fortunes was a massive failure. After they finished writing the Declaration of Independence and launched the colonies off into the Revolutionary War, the members of the Continental Congress haggled for more than a year as they drafted the Articles of Confederation. They finally finished it and sent it to the states for ratification at the end of November 1777, after the British had captured Philadelphia and thus made it abundantly clear that the colonies needed to get the matter of a central government settled.

It took more than three and a half years for all the colonies to ratify the articles, with Maryland holding out over the issue of other states’ right to claim western lands. When the British started raiding communities on the Chesapeake Bay and Virginia finally agreed to give up that right, Maryland ratified the articles, and it became the ruling document of the new nation on March 1, 1781.

After the Treaty of Paris was signed, however, and the states settled into their new order, the articles’ flaws became evident. They did not authorize the new central government to impose taxes to raise money. Instead, it had to ask the states for money, sell off its western holdings, or borrow from foreign governments. It could not regulate either foreign trade or interstate commerce. It could print money, but so could all of the states, so there was no uniform currency. The government could declare war, but it could not draft soldiers. The nation had no federal court system or executive branch of government. It could negotiate with foreign governments, but its lack of military might undermined its ability to enforce its negotiations.

Articles of Confederation

NARA’s Milestone Documents

“Sketch” of the Articles of Confederation – by Ben Franklin

NARA’s Philadelphia Exhibit

Read the full Articles of Confederation text

NARA’s Milestone Documents

To remedy this chaos, the states called a Constitutional Convention, which convened in Philadelphia in May of 1787. The delegates intended to address the issues with the Articles of Confederation and to amend them to create a stronger government. It soon became clear, however, that a completely new document was needed that would spell out the obligations and powers of the new central government. The delegates spent the summer debating the issues and drafting the document that they released to the states for ratification that September.

Resolution ratifying the Constitution

NARA’s Prologue Magazine

The Committee of Detail, comprised of John Rutledge, Edmund Randolph, Nathaniel Gorham, Oliver Ellsworth, and James Wilson, was charged with writing the first draft of the Constitution from a list of resolutions the rest of the delegates had drawn up. James Wilson is largely responsible for much of the language and structure of the final version of the Constitution. On September 8, the delegates turned the draft document over to the Committee of Style, comprised of William Samuel Johnson, Alexander Hamilton, Gouverneur Morris, James Madison, and Rufus King, “to revise the stile of and arrange the articles which had been agreed to by the House.”

George Washington’s working copy of the Constitution pg 1

NARA’s Prologue Magazine

George Washington’s working copy of the Constitution pg 2

NARA’s Prologue Magazine

The Preamble of the Constitution was written mostly because it was customary at the time for important documents to include an introductory statement. The draft Preamble of the Constitution bore little resemblance to the elegant sentence we now know: “We the People of the States of New-Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode-Island and Providence Plantations, Connecticut, New-York, New-Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North-Carolina, South-Carolina, and Georgia, do ordain, declare and establish the following Constitution for the Government of Ourselves and our Posterity.”

David Brearley’s annotated copy of the Constitution pg 1

NARA’s Prologue Magazine

David Brearley’s annotated copy of the Constitution pg 2

NARA’s Prologue Magazine

Bearley’s printed copy of the Constitution as of 9/13/1787

NARA’s Prologue Magazine

Gouverneur Morris, who represented Pennsylvania at the convention and who had been included in the committee primarily because of his rhetorical gifts, changed the opening to the ringing words, “We the People of the United States . . .”

(Incidentally, following that example, the preambles of the constitutions of 36 states also begin, “We the people . . .”)

The Preamble then states the reasons for establishing the Constitution: “. . . to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity. . .”

On September 17, 1787, the Constitutional Convention ended with the signing of the new Constitution and releasing it to the states for their consideration. On June 21, 1788, New Hampshire ratified the Constitution, becoming the ninth state to do so, and it became the law of the land.

View this profile on InstagramNational Archives Foundation (@archivesfdn) • Instagram photos and videos