The Sights and Sounds

When we think of New York City in the early twentieth century, most of us think of immigrants who had spent weeks at sea, yearning to get a glimpse of the Statue of Liberty, disembark at Ellis Island, and start anew in the land of opportunity. But in parallel, another important migration was occurring as Black communities took root in northern metropolises like Chicago, Detroit, Pittsburgh, and of course, New York City.

This migration not only signified one of the great demographic shifts in the U.S., but it also launched a new era of Black history. The arts, culture, and music scene there developed so prolifically and rapidly that it earned the same name as another era for arts and culture: the Renaissance period.

This week, we’re bringing you the sights and sounds of the Harlem Renaissance through the holdings of the National Archives.

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

Southern Exodus

Sharecropper in Washington Delta, Mississippi

National Archives Identifier: 512796

After Reconstruction ended in the American South in 1877, Black people living in that region rapidly lost many of the civil rights the Civil War had won for them. Racist lawmakers in both the federal and state governments passed laws that disenfranchised Black people and many poor whites. Furthermore, many African Americans lived in fear of being beaten, raped, and lynched and of having no legal recourse in the courts of the Jim Crow South.

To make matters worse, economic conditions for many Black people in the South were miserable. Most of them relied on agriculture to make a living, but few of them were able to buy land. Consequently, they were forced to work as sharecroppers, an arrangement that was at best one step up from slavery. Natural disasters like drought and the migration of the boll weevil into southern cotton fields, which decimated cotton production there, also encouraged Black people to look for better economic opportunities elsewhere.

Consequently, from roughly 1880 through 1960, millions of African Americans moved from the South to urban centers in the North, West, and Midwest. Harlem, the Upper Manhattan neighborhood in New York City bounded by Central Park North on the south, Fifth Avenue on the east, the Hudson River on the west, and the Harlem River and 155th Street on the north, had been home to Jewish and Italian Americans in the late nineteenth century, but around 1910, Black Americans began to move into the area. Foreign immigration to the U.S. dropped after World War I, so manufacturers headquartered in the North sent recruiters to the South to encourage Black people to take jobs in their factories. By the beginning of the second decade of the twentieth century, more than 300,000 African Americans had left the South for better prospects elsewhere. Many of those migrants settled in Harlem.

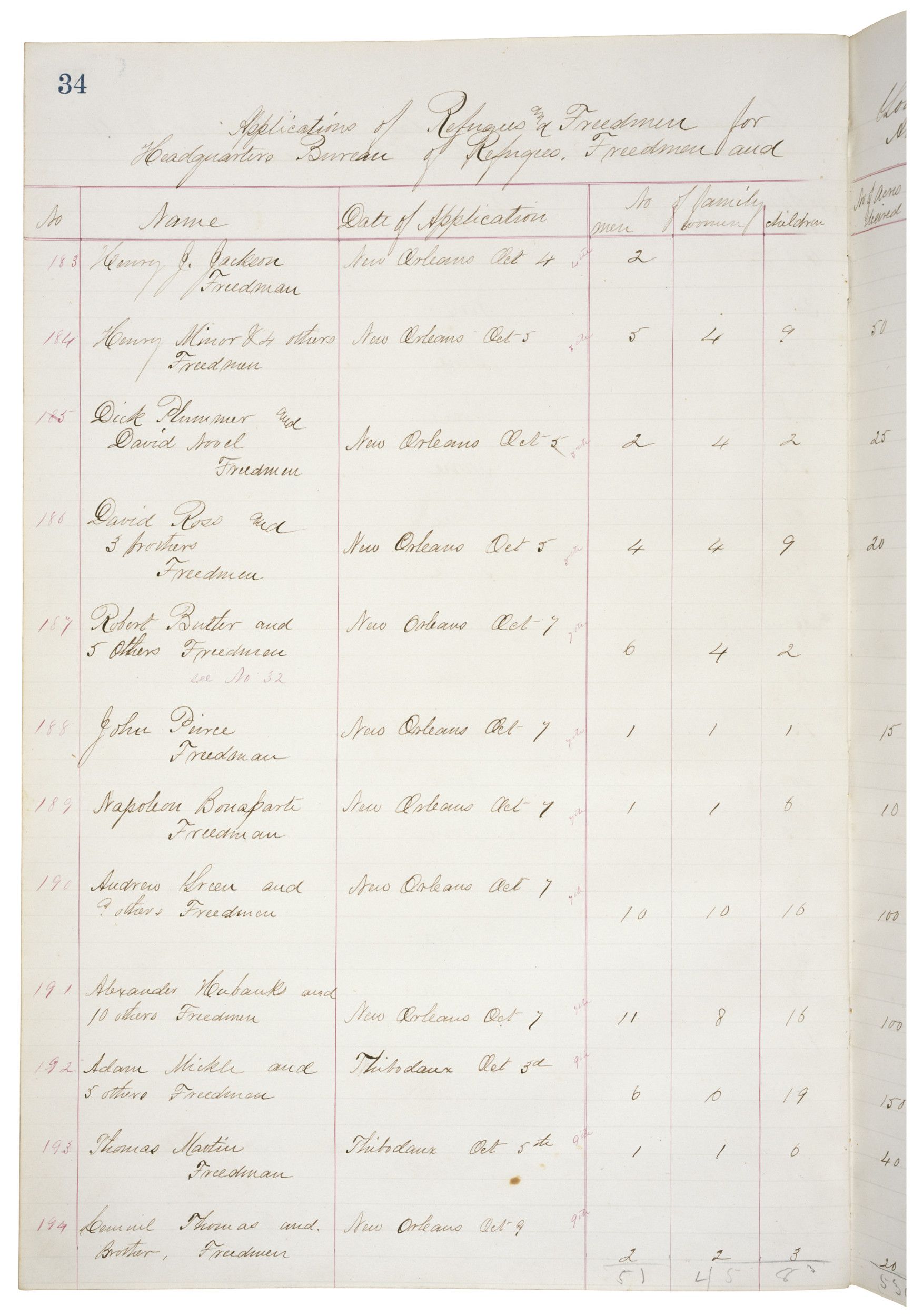

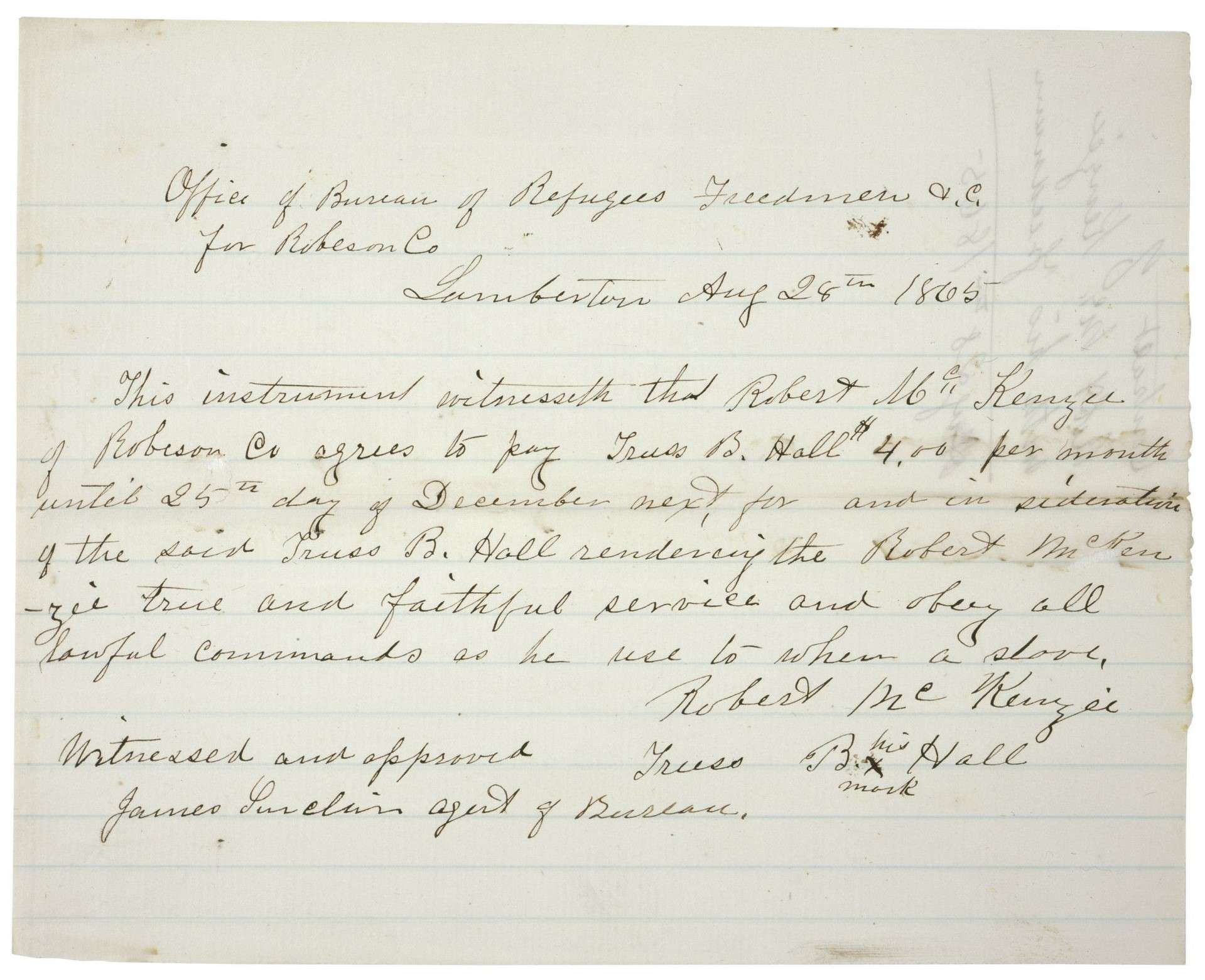

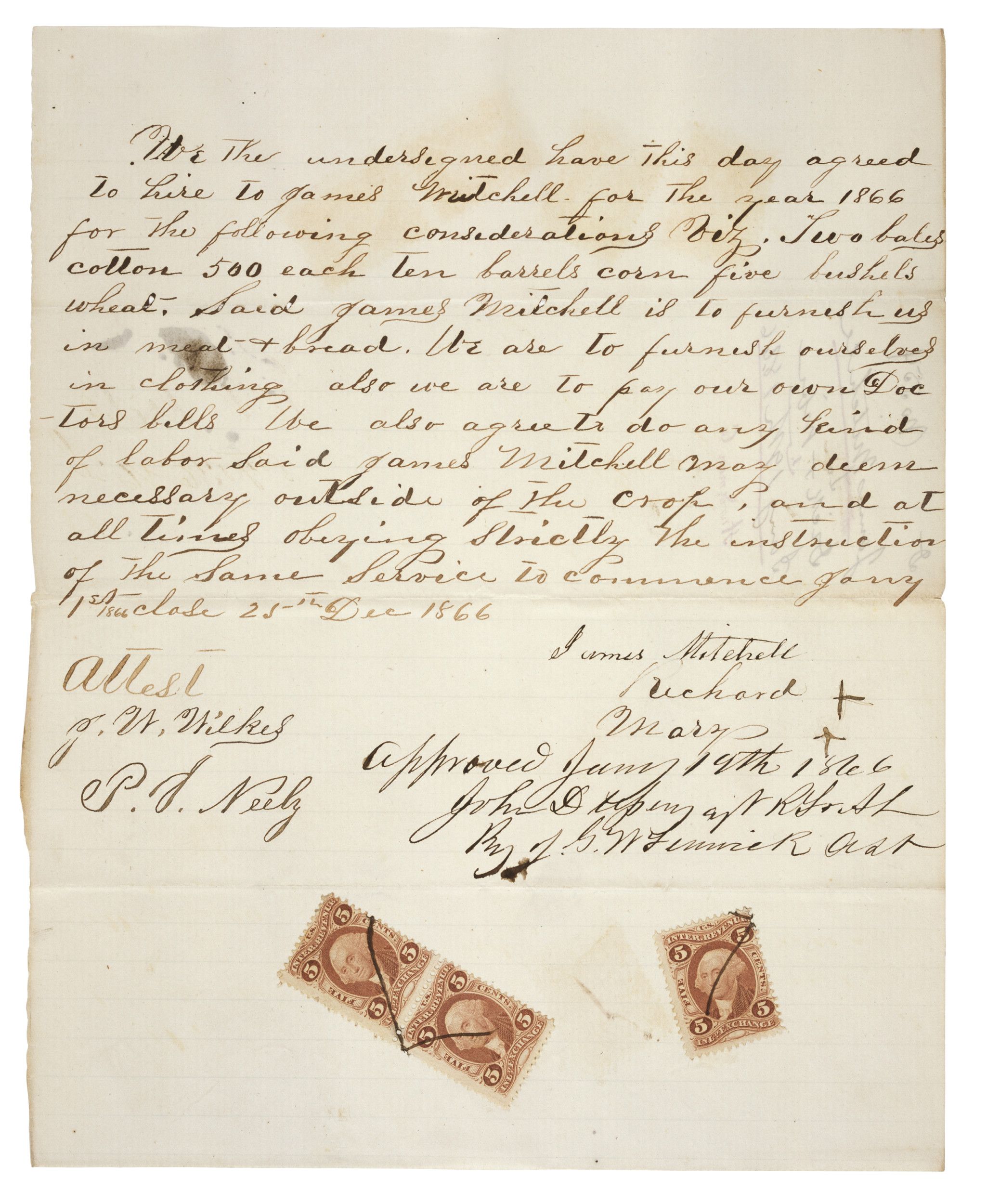

| Applications and Agreements | ||

|---|---|---|

Applications of Freedmen for Land Source: NARA’s DocsTeach |

Labor Agreement for Truss B. Hall to “Obey all Lawful Commands as he used to when he was a slave”, 1865 Source: NARA’s DocsTeach |

1866 Labor Agreement for Richard and Mary, formerly enslaved, to continue work on a Tennessee plantation National Archives Identifier: 512796 |

All That Jazz…and More!

The rapid influx of African Americans into Harlem in the first decades of the twentieth century gave rise to what is now called the Harlem Renaissance, a dynamic cultural flowering born of Black pride that began with poetry and literature and rapidly spread to include Black newspapers, criticism and political discourse, music and musical theater, and fashion. The roll call of writers, composers, musicians, and visual artists who flourished in this place and during this period is staggering: poets Claude McKay, Jean Toomer, Countee Cullen, and Langston Hughes; novelists James Weldon Johnson, and Jessie Redmon Fauset; musicians and composers Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Fats Waller, and Eubie Blake; singers Bessie Smith, Ethel Waters, and the young Lena Horne; dancers Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, Josephine Baker, and the Nicholas brothers, Fayard and Harold; all-around actor, singer, musical artist, writer, and activist Paul Robeson; and, in the visual arts, sculptor Meta Warrick Fuller; painter, muralist, and book illustrator Aaron Douglas; Augusta Savage, a sculptor who later persuaded black artists to work for the Work Projects Administration; and photographer James Van Der Zee; and the Black nationalist Marcus Garvey.

The Stock Market Crash of 1929 and the beginning of the Great Depression were the first blows to the Harlem Renaissance. When Prohibition was repealed in 1933 and alcohol became freely available all over New York, many businesses in Harlem lost most of their white clients who had been willing to travel uptown for entertainment. A race riot in Harlem in 1935 effectively ended the Harlem Renaissance.

Baltimore Buzz

(3 minutes 12 seconds – Audio Only)

Source: Internet Archive

To view the text of a document or the full image, click on the image displayed above

The Cotton Club

The Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibited the “manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors within, the importation thereof into, or the exportation thereof from the United States and all the territory subject to the jurisdiction thereof for beverage purposes. . .” It was an idea backed by good intentions, but as we know, many well-intentioned ideas don’t work out well. Prohibition turned out to be more honored in the breach than in the observance, and the abundance of jazz clubs and speakeasies in Harlem most certainly proved that.

The Cotton Club was a nightclub on the corner of 142nd Street and Lenox Avenue that offered Black entertainment to a white audience. Right in the middle of Harlem, it did not allow Black patrons entrée except for a handful of Black celebrities on very rare occasions.

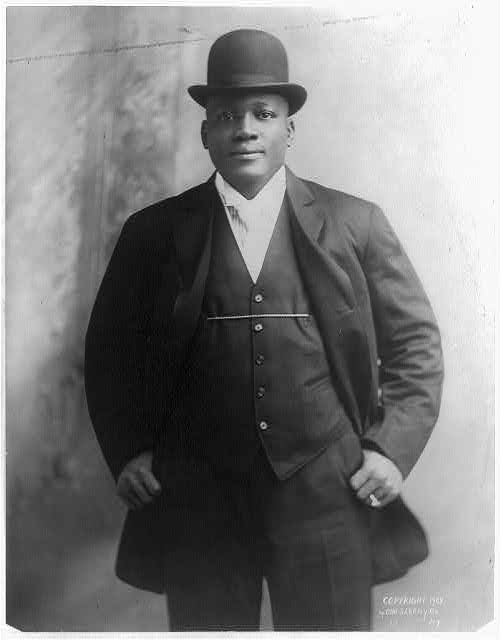

Jack Johnson

Originally opened by heavyweight boxing champion Jack Johnson in 1920 and called the Club DeLuxe, the property was acquired in 1923 by a gangster named Owney Madden, who let Johnson stay on as manager while Madden used the club as an outlet for bootleg liquor sales. The club sold food and drink, but its main attraction was a very elaborate floor show with black entertainers, including a chorus line, singers, dancers, comedians, and Duke Ellington’s orchestra, which was the house band from late 1927 until the end of June 1931. Cab Calloway and his orchestra performed at the club starting in 1930 and replaced Ellington’s when they left in 1931.

Cab Calloway

Operating at the Harlem location until 1936, the Cotton Club featured a long list of prominent and up-and-coming black performers: Ethel Waters, the Dandridge Sisters, Charles “Honi” Coles, Earl “Snakehips” Tucker, Fletcher Henderson, Jeni Le Gon, Jimmie Lunceford, The Four Step Brothers, Chick Webb, the Berry Brothers, Count Basie, Stepin Fetchit, Fats Waller, the Nicholas Brothers, Willie Bryant, Leonard Reed, Adelaide Hall, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, Bessie Smith, Katherine Dunham, Aida Ward, Lena Horne, Avon Long, Billie Holiday, the Will Vodery Choir, Nina May McKinnery, and Avon Long. Compared to other clubs in Harlem, the Cotton Club paid Black performers well, but they were not allowed to mix with the white patrons.

Cab Calloway’s baton

The Cotton Club was not without its critics, who objected to its blatantly racist policy of not allowing Black people to patronize it and to the stereotypical ways Black people were depicted in the floor shows as “jungle savages.” The chorus girls were required to be under twenty-one, tall, thin, and light-skinned. Langston Hughes also objected to the competition that the Cotton Club brought to Harlem, which he said unfairly affected smaller, Black-owned establishments.

After the race riot of 1935, the Cotton Club closed in Harlem, and another iteration opened in the Midtown theater district that remained open until 1940.

Cab Calloway orchestra at the Cotton Club

(3 minutes 18 seconds – Audio Only)

Source: Internet Archive

Shuffle Along

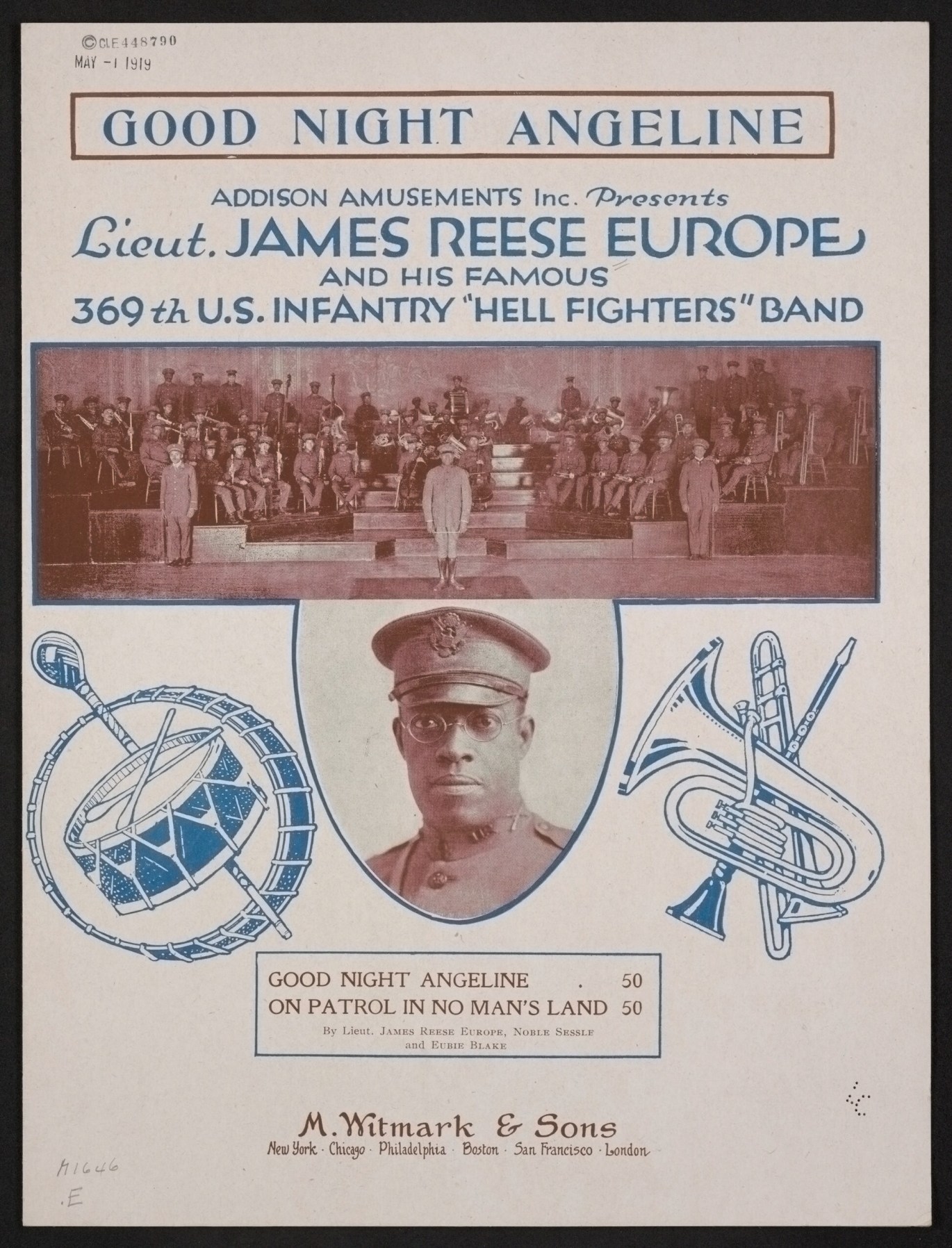

Sheet music cover for “Good Night Angeline”, composed in part by Eubie Blake

Among the many who produced landmark works of literature and music during the Harlem Renaissance, Eubie Blake is indeed a giant of American musical theater. He and Noble Sissle, with whom he collaborated for years, produced Shuffle Along, the first Broadway musical written and directed by Black Americans. Written along with the comedy duo Flournoy Miller and Aubrey Lyles, it premiered in New York in July 1921. Two of its songs, “Love Will Find a Way” and “I’m Just Wild About Harry,” went on to become hits.

George W. Bush proclamation for Black Music Month, 2008

Source: George W. Bush White House Archives

James Hurbert “Eubie” Blake was born in Baltimore, Maryland, on February 7, 1887, to James Sumner Blake and his wife Emily “Emma” Johnston, both former slaves. Eubie was the only one of their many children who survived to adulthood. From a very early age, he showed musical promise, so his parents bought a pump organ for him when he was four and sent him to a neighbor, who was the organist at the local Methodist church, for music lessons. By the time he turned fifteen, and most definitely without his parents’ knowledge, he was playing the piano at a local club. From there, he fashioned a career playing in hotels and clubs and on the medicine show circuit and vaudeville. In 1915, he met Sissle, and the two formed a partnership that lasted throughout the 1960s.

Eubie Black receives the Medal of Freedom from Reagan

National Archives Identifier: 75855833

Although Blake and Sissle had many successes both before and after Shuffle Along, that musical’s significance can hardly be overstated. It brought Black dancing and music to mainstream attention for the first time in New York City. Florence Mills and Josephine Baker both began their careers performing in Shuffle Along. The show ran on Broadway for more than 500 performances and went on to tour the country for several years. In 1948, Harry S. Truman adopted “I’m Just Wild About Harry” as his presidential campaign song.

Eubie Blake kept writing music and performing for all of his long life. He worked with the USO throughout World War II to produce music for their shows for U.S. servicemen, and in the 1950s and 1960s, he was recognized as a father of ragtime music and was featured on several ragtime records. He often performed on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson and on Saturday Night Live. In 1979, a Broadway retrospective, Eubie!, honored his life’s work. He received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Ronald Reagan in 1981. Eubie Blake died in Brooklyn on February 12, 1983, five days after his ninety-sixth birthday.

Eubie Black and Sissle

(2 minutes 30 seconds – Audio Only)

Source: Internet Archive

A Gallery in the Archives

In 1926, William E. Harmon established a foundation in his name to finance Black artists that produced art, from paintings and sculptures to music and poetry. Prominent recipients of his foundation’s prize money included big names like Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen, and Laura Wheeler Waring, but smaller and community-based artists received recognition and funding as well. By 1929, the foundation was also sponsoring traveling exhibits.

Beginning in February 1933, the Harmon Foundation hosted its fifth exhibit at the Art Center at 65-67 East 65th Street in New York City. The exhibit was called The Negro in Art, and a film of the same name documented the exhibit. In addition to watching the film, you can view over one hundred pieces of art sponsored by the Harmon Foundation in the Archives’ holdings.

(10 minutes 47 seconds – NO SOUND)

Source: NARA YouTube Channel

| View the Archives’ entire collection of Black Artists from 1920-1929 |

||

|---|---|---|

Sculptor Richmond Barthé |

Sculptor William E. Artis |

Traveling exhibit photo, Baltimore |