Pride in the Archives

As the calendar turns to June, citizens of all ages and institutions publicly recognize their allyship with the LGBTQ+ community. It’s easy to forget that Pride is one of our country’s youngest traditions. The first “official” Pride month was celebrated in June 1999, when President Bill Clinton declared the first recognition of “Gay & Lesbian Pride Month.” Over the years, it has expanded to be more inclusive, with President Biden declaring June 2021 “LGBTQ+ Pride Month.”

But like other groups of individuals who have fought for their rights, “Pride” didn’t come without stigma and struggle. Since the mid-twentieth century, the LGBTQ+ community has had to fight for recognition and acceptance before fighting for basic protections and rights.

This week’s edition tells the stories of a community of citizens who were ignored, shamed, and denounced – and of the courage of gay rights trailblazers who faced threats, violence, and long public legal battles for equality.

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

A Hidden History

Jane Addams was a progressive social activist who led the settlement house movement in the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. She was an outspoken proponent of women’s rights and a pacifist who saw her personal popularity wax and wane as a consequence of her pronouncements. Over the course of her life, she counseled seven American Presidents. In 1931, she won the Nobel Peace Prize, the first American woman to be so recognized. She is also now known to have been in a committed same-sex relationship with her partner, Mary Rozet Smith, for forty years at a time when such relationships were not publicly acknowledged.

Jane Addams was born on September 6, 1860, in Cedarville, Illinois, to John H. Addams, a banker, businessman, founding member of the Illinois Republican Party, and Illinois state senator, and his wife, Sarah Addams. Although the family were prominent and well-to-do, they were not immune to the common tragedies of the times. Sarah Addams died in childbirth when Jane was two, as did her baby. In all, four of Jane’s eight siblings died by the time Jane was eight.

When Jane herself was four, she contracted tuberculosis of the spine. She suffered from curvature of spine and other debilitating health issues for the rest of her life as a result.

Jane was a bright child and an avid reader who longed to help others. When the time came for her to attend college, she asked her father to let her go to Smith College in Massachusetts, which was brand-new, but he insisted that she attend Rockford Female Seminary in Rockford, Illinois, instead. The summer after she graduated in 1881, her father died of appendicitis and left each of his children $50,000, equivalent to $1.4 million in 2022 dollars. Along with their stepmother, Anna Haldeman Addams, Jane, her sister Alice, and Alice’s husband Harry moved to Philadelphia that fall. The two women enrolled in the Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, while Harry continued his medical studies at the University of Pennsylvania. Jane completed one year there, but ill health forced her to drop out of school. The whole family then moved back to Cedarville.

Her brother-in-law performed surgery on Jane’s back the next fall. When she had recovered, he advised her to travel rather than continuing her studies, so she spent the next several years alternating travel with living with her stepmother in Cedarville and Baltimore. She also continued to read and to think about how she could live a more fulfilling and useful life.

In 1887, Addams learned about the settlement house movement in England, in which middle-class volunteers moved into houses in poor areas of a city and offered services such as health care, day care, and English-language classes to the poor people who lived around them. In 1889, with her first romantic partner Ellen Gates Star, Jane Addams established Hull House on South Halsted Street in Chicago. Funded in the beginning with Addams’ own money, Hull House soon became a haven for the local immigrants, who were mainly Polish Jews, Russians, Bohemians, Italians, and Germans. The workers at Hull House offered day care and kindergarten classes for children and night classes for their parents, a savings bank, an employment bureau, arts and crafts classes, and men’s clubs. The locals were suspicious of the apparent do-gooders who lived in Hull House at first, but they soon were won over. By the end of the first year, 50,000 people had visited the facility. At the end of its first decade, the staff had increased to twenty-five people.

National Register for the Hull House

National Archives Identifier: 28891596

From the founding of Hull House, Addams had the good fortune to attract wealthy and dedicated donors who believed ardently in her cause. One of them was Mary Rozet Smith, who also became her life partner. Many of Addams’ biographers seem reluctant to conclude that Addams and Smith were in a committed same-sex relationship, at least partly because Addams herself embraced the ideal of platonic love early in her life, but based on the historical record and their own correspondence, there is no doubt that Jane Addams and Mary Rozet Smith were devoted to one another for the forty years they were together. The two of them lived together, owned a home together in Maine, and wrote to one another at least once and sometimes twice a day when they were separated. In 1902, Addams wrote to Smith, “You must know, dear, how I long for you all the time. . . . There is reason in the habit of married folks keeping together.” Smith died of pneumonia in 1934; Addams died of cancer in 1935.

Although throughout her life Jane Addams gained a reputation as a radical pragmatist, she was adamantly dedicated to certain ideals, including women’s rights, children’s protections, and pacifism. She opposed the United States’ entry into World War I and was booed offstage at Carnegie Hall when she gave a speech on the subject in 1915. She was a co-founder of the American Civil Liberties Union.

To view the full text of a document, click on the document when it’s the main image above

“Gay is Good”

On April 23, 1953, President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed “Executive Order 10450: Security Requirements for Government Employment,” which charged the FBI with investigating whether applicants for federal jobs or employees posed security risks to the government. The criteria the bureau were authorized to use were extremely broad: “Any criminal, infamous, dishonest, immoral, or notoriously disgraceful conduct, habitual use of intoxicants to excess, drug addiction, or sexual perversion.” The Red Scare was already in full swing, but less well remembered now is the “Lavender Scare,” during which people suspected of being gay were refused employment or fired on the grounds that they could be blackmailed and therefore posed a risk to national security.

Frank Kameny was an astronomer who had barely gotten the seat of his office chair warm at the U.S. Army Map Service in Washington, D.C., when he was dismissed from his job for being gay. Kameny was born in New York City in 1925. He graduated from high school at the age of sixteen and went to Queens College, but his education was interrupted when he was drafted into the Army to fight in World War II. He served in Europe and then worked for the Selective Service board for twenty years before he completed his bachelor’s degree at Queens College.

Kameny then studied at Harvard, where he completed both a master’s degree and a doctorate in astronomy. He took a trip across the country and was arrested in San Francisco after a stranger groped him in a bus station. Although he had been assured that if he didn’t contest the charges, his record would be expunged after three years, his employers at the U.S. Army Map Service learned of his arrest and questioned him about his sexual orientation. Kameny refused to answer their questions. The commission fired him and then barred him from federal employment.

To say Kameny took his dismissal badly is an understatement. The experience turned him from a mild-mannered intellectual who was completely devoted to his work into a radicalized activist hellbent on fighting for the rights of gay people.

First, Kameny appealed his dismissal through the judicial system, taking it all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which refused to review the lower court’s decision to affirm his firing. In 1961, he and the activist John “Jack” Nichols then established the Washington, D.C., branch of the Mattachine Society, a gay-rights organization established in Chicago in 1950. When some members of Congress learned that the society was raising funds to promote gay rights in the District of Columbia, they introduced legislation specifically written to prevent such organizations from receiving fundraising licenses there.

Frank Kameny asked Subcommittee No. 4 of the House Committee on the District of Columbia to permit a representative of the Mattachine Society to testify about the pending legislation, and they allowed him to do so. He forcefully rebutted the arguments of those who contended that an organization promoting the rights of gay people in the district would threaten the common good. In the end, the House of Representatives passed an amended version of the bill, but the Senate did not act on it.

Kameny continued to advocate for gay rights, leading protests at the Pentagon, the White House, the Civil Service Commission, and the Pentagon in Washington for several years. He ran for Congress as Washington, D.C.’s delegate in 1971. Although he lost the election, he was the first openly gay candidate to run for the office.

To view the full text of a document, click on the document when it’s the main image above

The First Pride Was a Riot

On June 28, 1969, a police raid on the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village in New York City sparked a series of riots and demonstrations by members of the gay community in protest of their treatment at the hands of the police. The riots marked the turning point in the gay rights movement in the United States, giving birth to the Gay Liberation Front, important new gay publications, and the Gay Pride movement.

In New York City in the early 1960s, Mayor Robert F. Wagner, Jr., was hard at work getting rid of gay bars to protect the city’s “image.” Liquor licenses were being revoked, and uncover cops were routinely entrapping gay men in compromising positions and arresting them for solicitation. When John Lindsay was elected mayor in 1966, the Mattachine Society managed to persuade him to back off the campaign of police entrapment, but the society had less luck with the state liquor authority, which was reluctant to issue licenses to businesses that catered to clientele that might become “unruly.”

Consequently, there were no gay-owned bars in New York in 1969; in fact, almost all of the bars where gays and lesbians gathered were owned by the Mob. The Stonewall Inn was no exception, and it most definitely was not the Ritz-Carlton. It had no liquor license, so the organized crime family that owned it paid the cops off each week to overlook its many legal violations. Dirty glasses were not washed—they were just rinsed and reused immediately. Toilets constantly overflowed on the restroom floors. There were no fire exits.

The police raided the Stonewall regularly, arresting the patrons and hauling them down to the jailhouse, but the bartenders were usually warned ahead of time that a raid was imminent. Just after 1 a.m. on Saturday, June 28, 1969, however, eight police officers abruptly entered the Stonewall Inn and announced they were raiding the place. They instructed the patrons to line up and present their identification, but the patrons began to refuse to do so. The police then decided to confiscate all the liquor in the bar and to transport all those present to the police station, but a delay in the arrival of police transport and a growing crowd outside interfered with this plan.

The police began to release some of the patrons, but rather than leaving, many of them joined the crowd, which was becoming increasingly unruly. When a police wagon finally arrived and the officers started loading people into it, members of the crowd started throwing bottles and bricks at the cops. Trash was set on fire, and protesters, many of whom hadn’t even been inside the Stonewall, were arrested and tossed into the paddy wagons. In the end, several police officers barricaded themselves inside the Stonewall Inn for their own protection.

Many individuals who participated in the riots stated that when the police raided the Stonewall, they felt a collective sense that they were through with accepting the way the police had been treating them. Marsha P. Johnson, a drag queen who had been one of the first to start going to Stonewall after drag queens and women were allowed inside it, said later that they weren’t there when the uprising started, but that they arrived soon afterward.

The Tactical Patrol Force, a riot control division of the police department, then showed up to free the cops who were hiding out in the Stonewall Inn. In response, many of the protesters formed a kick-line, dancing and singing and mocking the policemen, who advanced on them, swinging their nightsticks. Some of the protesters ran away from the policemen and then emerged behind them in the lower city block to taunt them again. In the end, that night, thirteen people were arrested, four policemen were injured, and several people were taken to the hospital. The Stonewall Inn was almost completely destroyed.

That was most certainly not the end of the event, however. The next night, Sunday, literally thousands of people filled the streets around the Stonewall, and several people confirmed that Johnson climbed a lamp pole and dropped a heavy bag onto the windshield of a police car, breaking it. By then, The New York Times, the New York Post, and the Daily News were all covering the riots.

Read the entire application for Stonewall Inn on the National Register

National Archives Identifier: 75319963

It rained on Monday and Tuesday, and things settled down a bit around the Stonewall, but on Wednesday, in response to an unflattering report of the conduct of the gay protesters in The Village Voice, an angry mob flooded into Christopher Street and a riot broke out. Businesses were looted, and the mob threatened to burn the offices of The Village Voice down. Periodic unrest in the area continued for nearly a week.

In the immediate aftermath of the riots, many gay activists decided that the mannerly tactics of the Mattachine Society were no longer effective, and they adjusted their approaches to political activism accordingly. The Gay Liberation Front was established, and Gay, Come Out!, and Gay Power became the first citywide gay publications to hit the streets.

A Forbidden Prom-posal

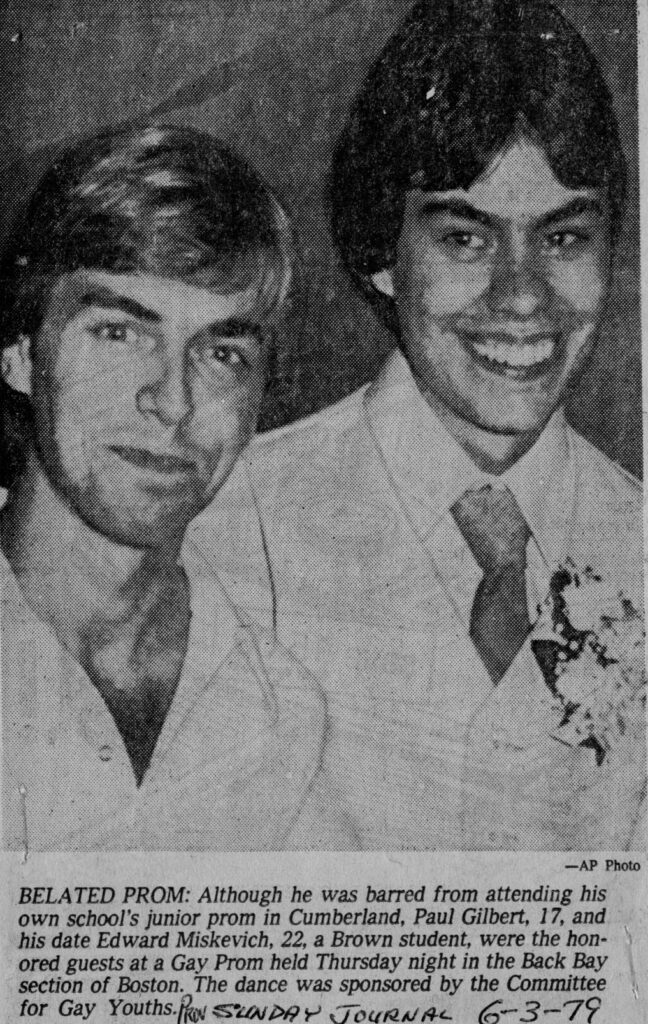

Belated Prom

The Providence Sunday Journal [sic] 6-3-79

National Archives Identifier: 29033010

page 35

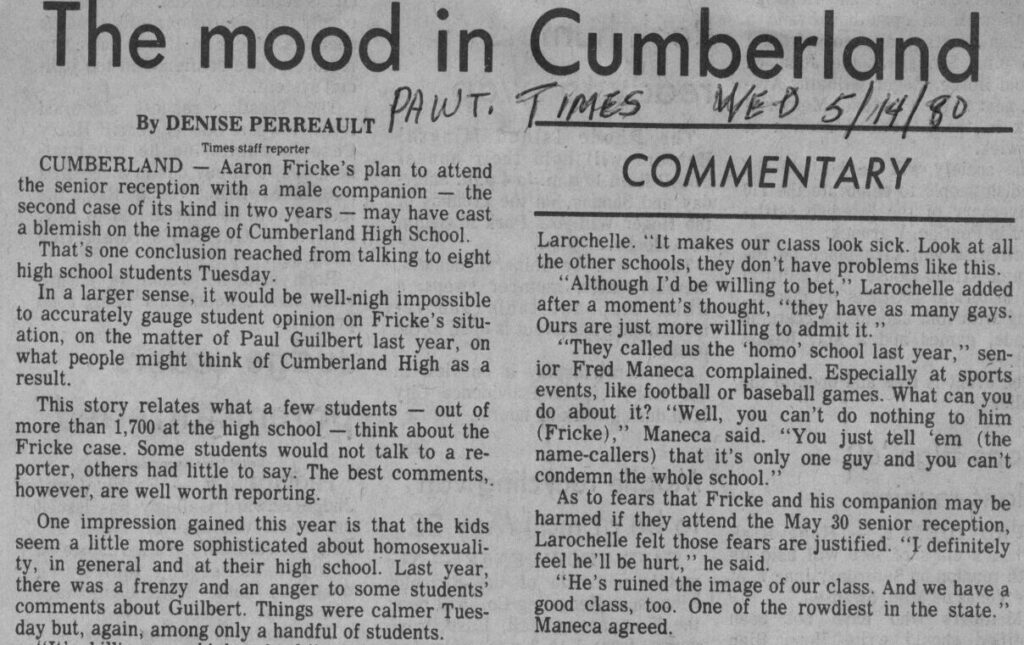

The mood in Cumberland

The Evening Times (Pawtucket, R.I.)

Thursday, May 14, 1980

page 13

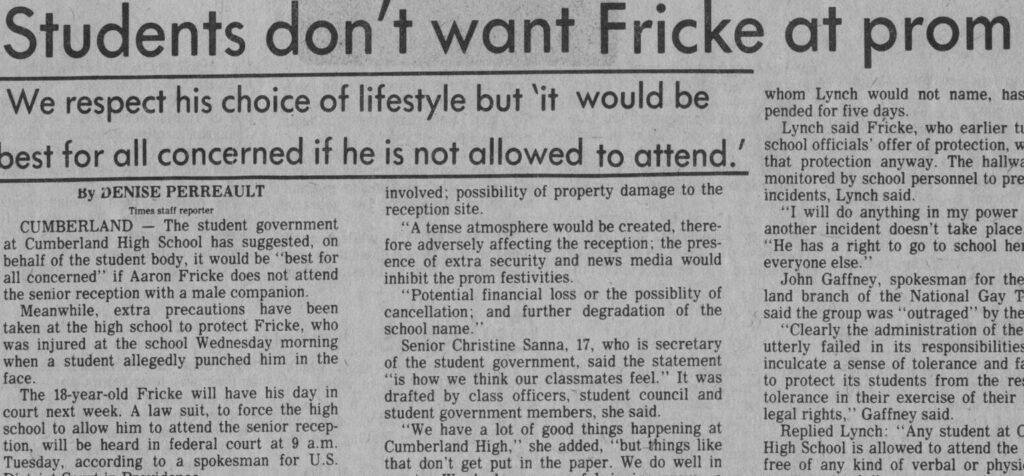

The Evening Times (Pawtucket, R.I.)

Thursday, May 15, 1980

page 11

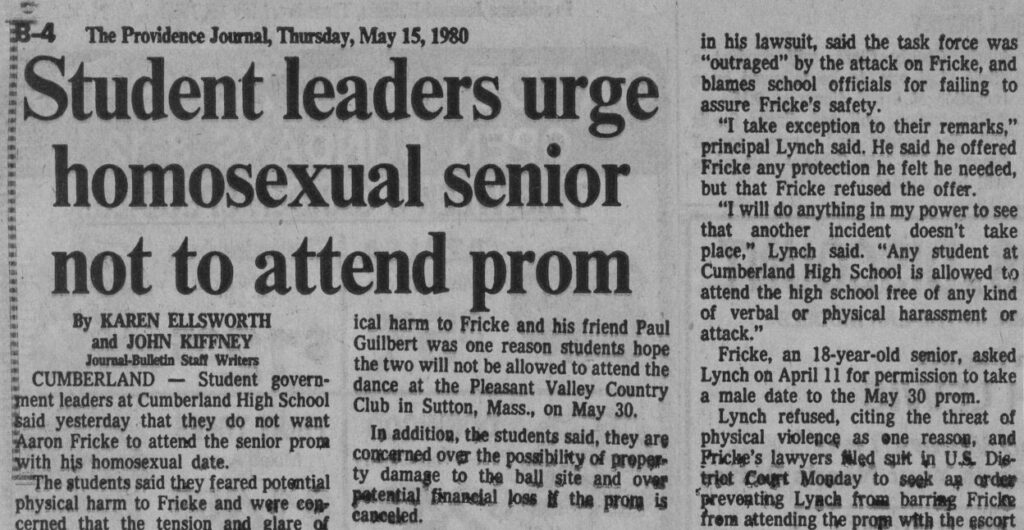

The Providence Journal

Thursday, May 15, 1980

page 12

National Archives Identifier: 29033010, pages 11-13

In 1980, Aaron Frick asked his high school principal, Richard Lynch, for permission to take a male date to the senior prom at Cumberland High School in Rhode Island. Lynch refused on the grounds of the “real and present threat of physical harm to [Fricke], [his] male escort and to others.”

Believing his civil rights were being violated, Frick sued Lynch in his role as principal of the high school in the United States District Court for the District of Rhode Island. The court ruled in Frick’s favor, stating “even a legitimate interest in school discipline does not outweigh a student’s right to peacefully express his views in an appropriate time, place, and manner.” With a heavy police guard in attendance, on May 31, 1980, Aaron Frick and his male date attended the prom. Since that time, other schools have been increasingly willingly to allow same-sex couples to attend dances.

Saying “I Do” to Marriage Equality

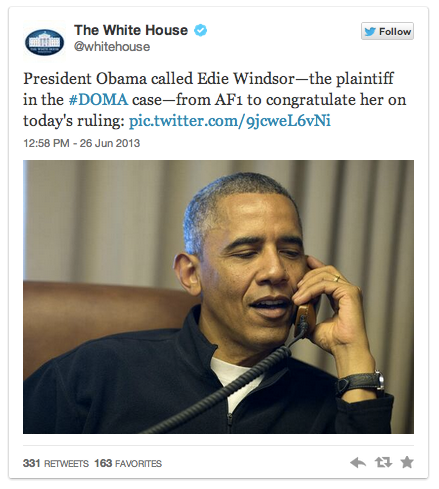

President Obama calls Edith Windsor upon the overturn of DOMA

Edith Windsor went to war with the U.S. government over what might seem the most mundane of matters—a tax bill. After all, in life, only two things are inevitable, death and taxes, right? But when Windsor’s wife, Thea Clara Spyer, died in 2009 after a long battle with multiple sclerosis, Windsor got hit with a stunner of a federal estate tax bill—$363,053—because under Section 3 of the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), which was passed in 1996 and signed into law by President Bill Clinton, the federal government did not recognize the validity of their marriage.

Edith Windsor met Thea Spyer in 1963 and began dating her in 1965. At the time, Windsor was working for IBM as a mainframe programmer, and Spyer was a psychologist. In 1967, they became engaged, although same-sex marriage wasn’t legal in the United States then. They moved into an apartment in Greenwich Village together in 1968 and then bought a house on Long Island. They were together for the next forty years.

After Spyer’s MS diagnosis, Windsor retired early to take care of her. When domestic partnerships between same-sex couples were legalized in New York, they applied for and were granted one in 1993. In 2007, when Spyer was told she had only a year to live, the couple married in Toronto, Canada, before Justice Harvey Brownstone, Canada’s first openly gay judge. Upon Spyer’s passing, Windsor was the executor and sole beneficiary of her wife’s estate.

Edith Windsor sued the federal government in 2010 for a refund of the estate tax bill in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York. In 2012, she won her suit when Judge Barbara S. Jones ruled that Section 3 of DOMA violated the due process guarantees of the Fifth Amendment. Jones ordered the federal government to issue the tax refund, including interest. Appeals of the case went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which affirmed Judge Jones’ decision in Edith Windsor’s favor.

President Obama speaks on the overturn of DOMA (9 minutes 4 seconds)

Related Content