Perseverance and Preservation

The efforts to maintain our nation’s most heralded documents and shared history are always works in progress. This week’s Archives Experience delves into some of the historic threats to record preservation that the nation and the National Archives have overcome.

From the tumultuous days of the War of 1812, when British forces razed the capital, to harrowing fires that threatened to consume irreplaceable service records, our country and eventually the National Archives has endured countless countless trials in its mission to safeguard the nation’s historical records. These events highlight more than just the physical threats to our invaluable documents. Over time, both elemental disasters and human flaws posed threats to the longevity of many documents, including, but not limited to, insects, light exposure, and humidity.

The First Flame: The War of 1812

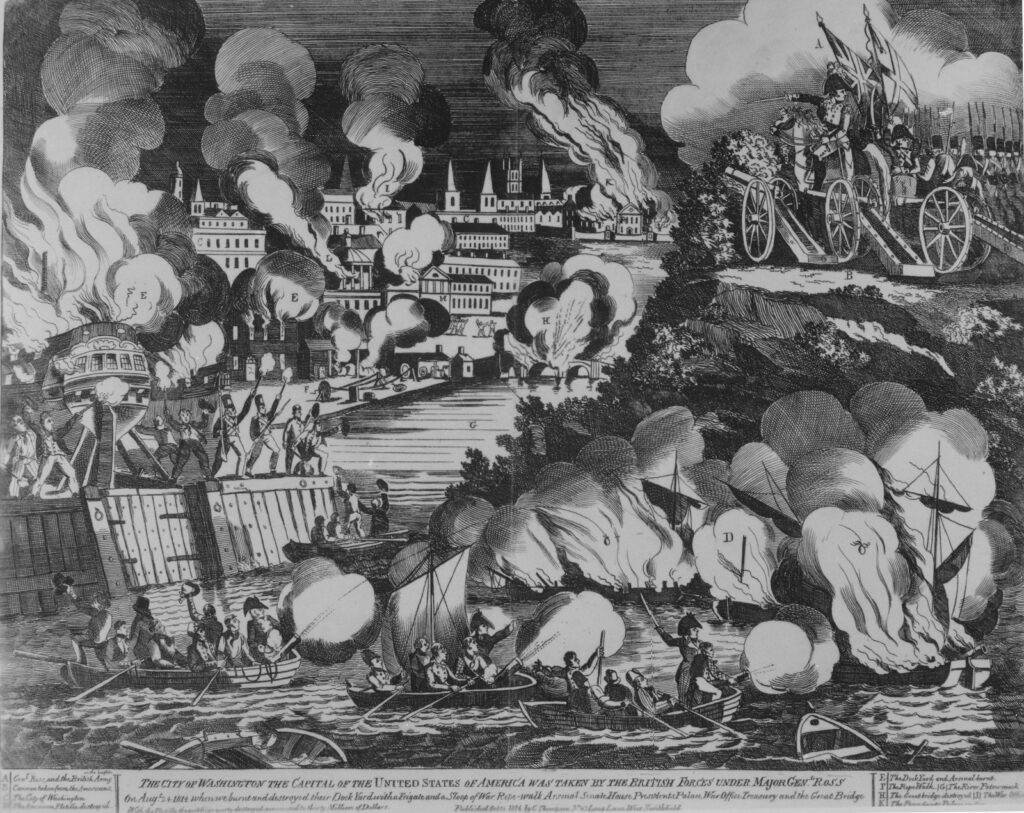

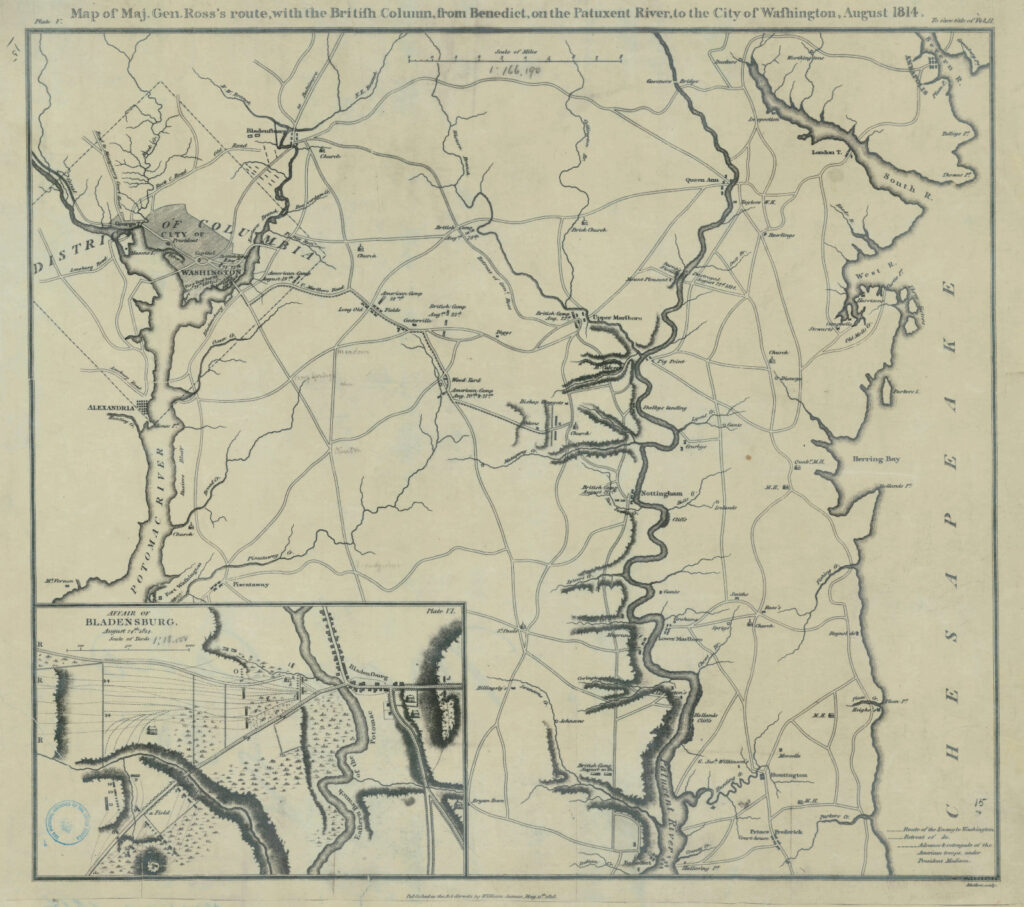

The War of 1812 was a catalyst for historic preservation in the young nation. The destruction of official papers by British forces in August 1814 was especially devastating. During this event, British troops set fire to several U.S. government buildings, including the Capitol and the White House, resulting in significant damage and loss of records and documents.

Copy of 1814 Engraving Depicting The Taking of the City of Washington

National Archives Identifier: 532909

Prior to Congress’ establishment of the National Archives, each executive department was responsible for its own internal recordkeeping. Records were stored in many places, and not with long-term preservation in mind. Notably, the Department of State was entrusted with the critical duty of preserving the nation’s early state papers, including the Charters of Freedom.

Map showing the route of the British invasion into Washington, August 1818

Records of the Office of the Chief of Engineers, National Archives

NARA’s Prologue Magazine

With news of the imminent British invasion in early August 1814, several clerks at the State Department took on the urgent task of protecting the Charters of Freedom and other essential documents. Although they did succeed in protecting some of America’s most cherished, foundational records, thousands of other papers did not survive the burning of Washington.

“Capture of the City of Washington,” August 1814

National Archives Identifier: 531090

Whose Records? Whose History?

Even before the Southern Confederate bloc formally seceded, commentators in the mid-19th centuries ruminated over what records belonged to whom. Did the Confederates have any claims to documents of national importance if they had seceded? This debate was heightened by the fact that Washington City, where most federal records were maintained, was quite literally a border city, situated directly between the North and the South.

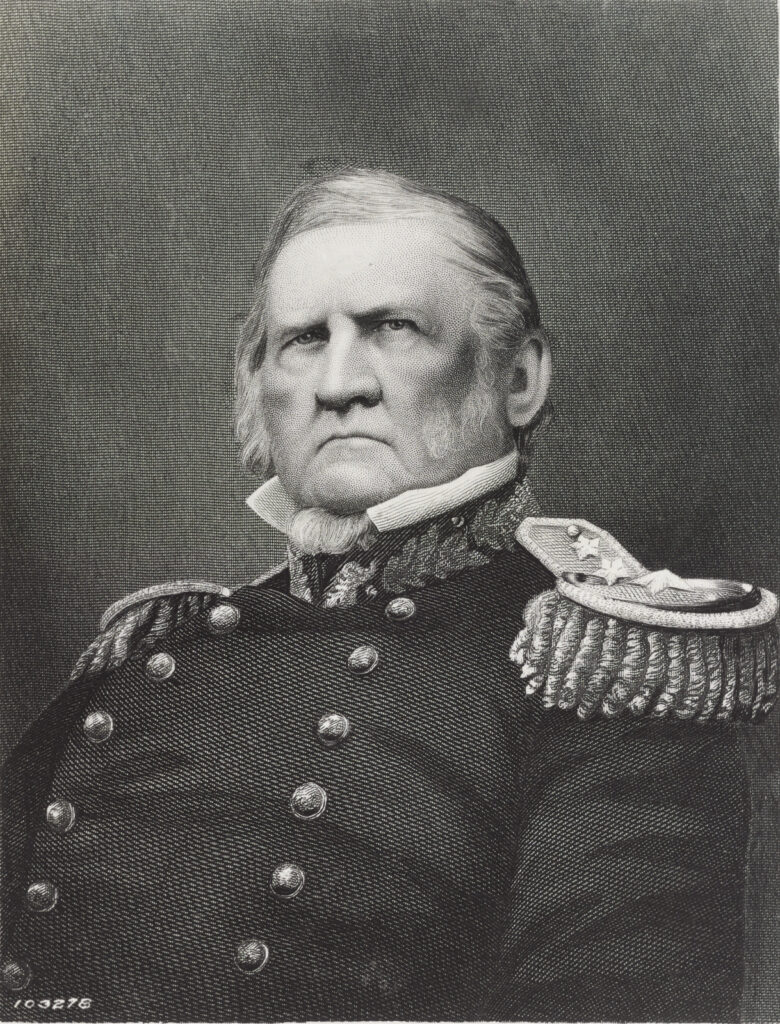

The fear over the Confederates seizing the records reached its peak in April 1860, when General Winfield Scott ordered his Washington-based soldiers to assemble for “the defence of the Government, the peaceable inhabitants of the City, their property, the public buildings, and public archives.” While at this time federal records were kept in the Capitol building, nearly 25,000 troops were rallied to defend the nation’s archives.

Winfield Scott

National Archives Identifier: 329591320

Conversations and actions over the nation’s document-based heritage did not stop at the onset of war. Many newspapers and letters on behalf of Confederate generals and even Jefferson Davis himself explicitly mentioned measures to safeguard official print materials. In Texas, for example, the state archives were surrendered to Confederate rule in 1861.

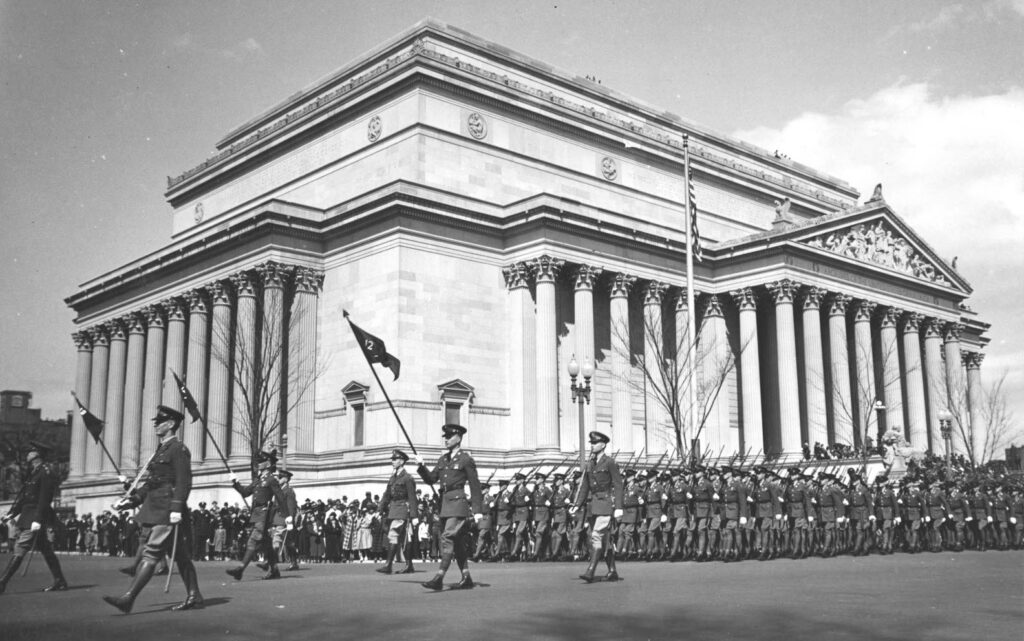

At the outset of World War II, officials at the National Archives prepared to be a target for enemy troops should the worst happen. President Franklin D. Roosevelt established the Committee on Conservation of Cultural Resources in 1941 for the express purpose of keeping cultural heritage, specifically paper records, out of harm’s way. While in the care of the Library of Congress at the time, the Declaration of Independence was sent to Fort Knox, Kentucky.

Army Day Parade in front of the National Archives Building, Washington, DC

National Archives Identifier: 12168466

In times of war, archives may not be the first things that come to mind as military targets. However, these instances underscore how valuable they truly are, and why archives are worth protecting.

Learning from the Ashes

While the fires that blazed in Washington in 1814 were certainly an existential threat at the time, the National Archives has experienced other close calls from the elements.

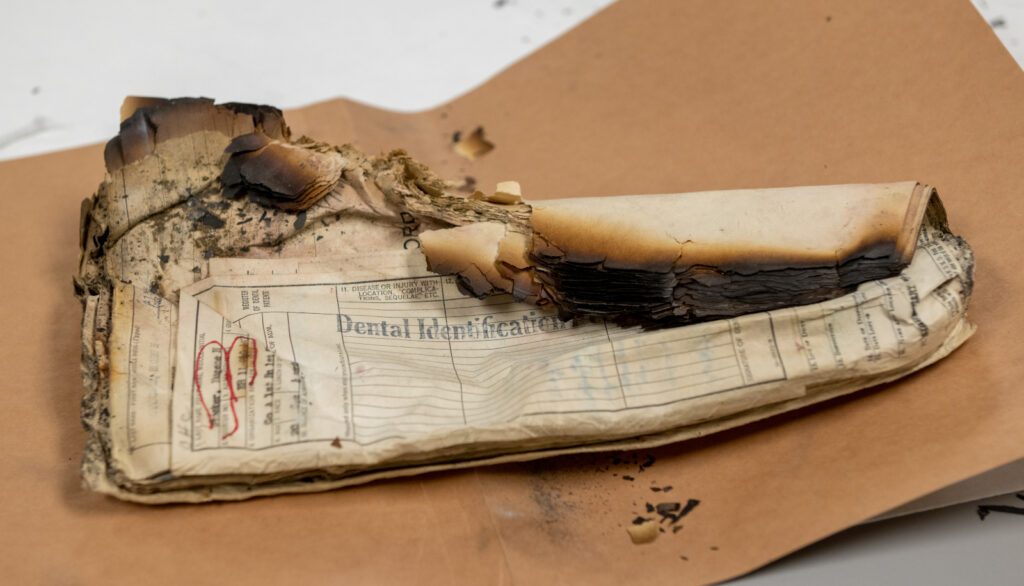

In July 1973, the National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) in Overland, Missouri, caught on fire. The blaze broke out on the top floor of the building, ultimately destroying the entire floor but sparing the lower levels from extensive damage. Researchers estimate that anywhere from 16 to 18 million documents were lost in the incident.

Burned document with mold and water damage from the 1973 NPRC fire

U.S. National Archives flickr

Thanks to the building’s design and automatic sprinklers, the fire did not spread beyond its initial location. Firefighters managed to contain the flames with minimal risk to the rest of the structure. However, the incident highlighted vulnerabilities, particularly the potential for flames to reach lower floors and compromise the entire facility.

In observation of the 50th anniversary of the tragedy, historians at the National Archives worked to gather the testimonies from over a dozen National Archives staff who worked at the Missouri branch at the time of the fire and of conservationists tasked with restoring some damaged documents. You can listen to the incredible stories from these dedicated civil servants here.

Archives in Progress

This history only reinforces the importance of preserving our nation’s documents. The National Archives is not just a static place to visit or do research. The proactive preservation work that goes on here is centered around “future proofing”—the act of ensuring generations in the next decades and centuries have the same, and improved, access to our shared American story.

Related Content

Remembering 9/11 Through Photographs

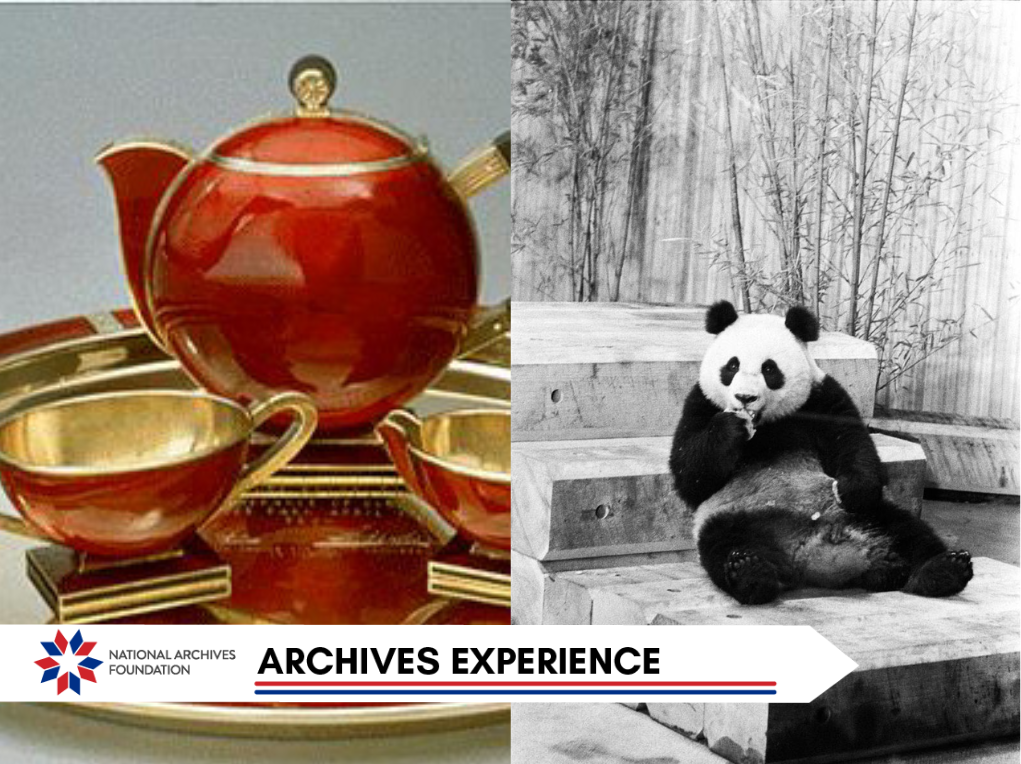

Crafting State Diplomacy Through Gifts