Dear Miss Perkins: A Story Found in Record Group 174

This week in honor of Women’s History Month, we bring you an Archives Experience guest written by one of our 2023 Cokie Roberts Fellows: Dr. Rebecca Brenner Graham. In this newsletter, she delves into her fellowship research and the experience of navigating archival records relating to Frances Perkins while she was writing her new book, Dear Miss Perkins: A Story of Frances Perkins’s Efforts to Aid Refugees from Nazi Germany. Dr. Graham is currently a postdoctoral research associate at Brown University. She holds a Ph.D. in history and an M.A. in public history from American University.

The Cokie Roberts Fellowship encourages the next generation of historians, journalists, and authors to continue Cokie Roberts’ legacy of bringing to light the stories of countless women in U.S. history that were previously unknown. This year’s application period is open until April 14.

My new book, Dear Miss Perkins: A Story of Frances Perkins’s Efforts to Aid Refugees from Nazi Germany, takes its name from the letters that Frances Perkins, FDR’s Secretary of Labor, received from people she had known from all stages of her life and career on behalf of refugees attempting to flee Nazi Germany. The Immigration Naturalization Service (INS) was in Perkins’s Department of Labor. Chapter seven, also titled “Dear Miss Perkins,” highlights several individual cases from the Secretary of Labor’s subject files, Record Group (RG) 174, which houses thousands of these letters. Together they represent a patchwork, piecemeal system in which Perkins helped explain unclear processes and intervened in hundreds of individual cases, despite restrictive, xenophobic structures.

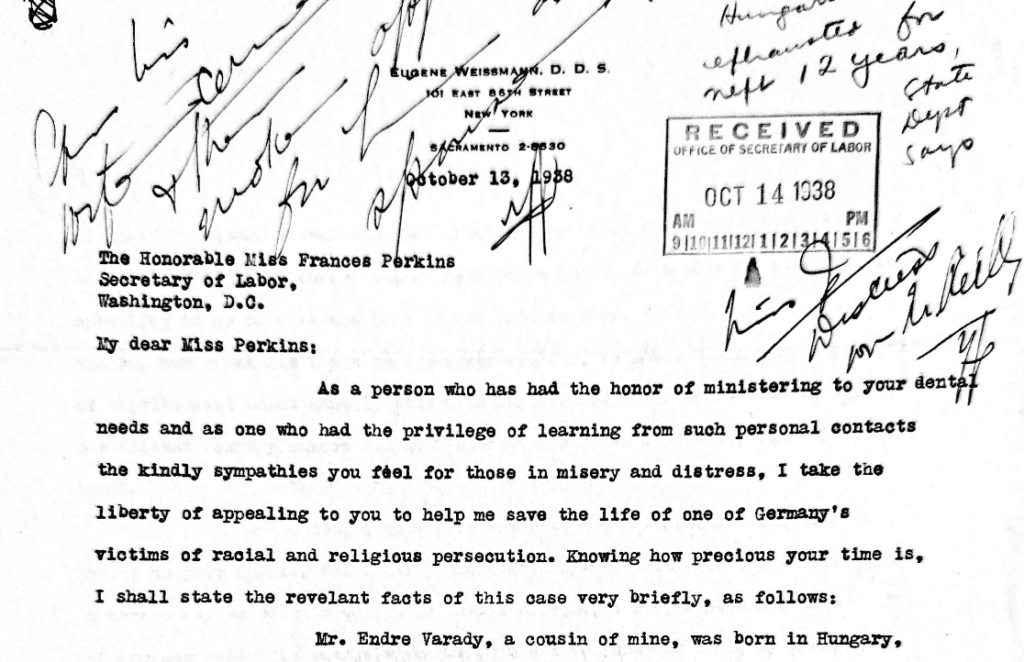

Endre Varady: Cousin of Perkins’s Dentist, 1938

In October 1938, just one month after Kristallnacht, Perkins’s dentist, Eugene Weismann, wrote to her on behalf of his cousin, Endre Varady, who was trapped in Austria. Born in Hungary, Varady and his family were waiting on a decades-long waitlist for a slot on the Hungarian quota to immigrate to the U.S. These restrictions were out of Perkins’s control, but thankfully, Varady and his family found refuge in New Zealand.

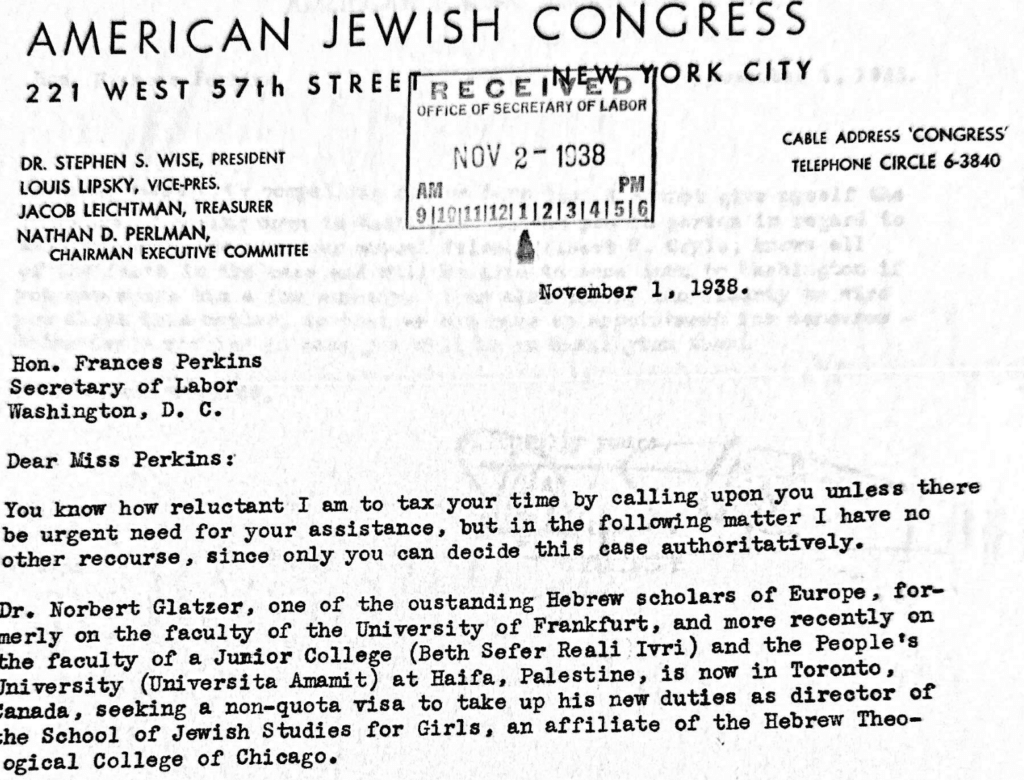

Norbert Glatzer: Professor and Scholar, 1938

Jewish activist Rabbi Stephen Wise wrote to Perkins on behalf of Norbert Glatzer, a Jewish scholar who lost his teaching position in Germany. On Glatzer’s behalf, Perkins assured the State Department consular official in Toronto that Glatzer’s research qualified him as a professor on a non-quota visa. Glatzer made it to the U.S. because of this work, and he continued to have a successful career.

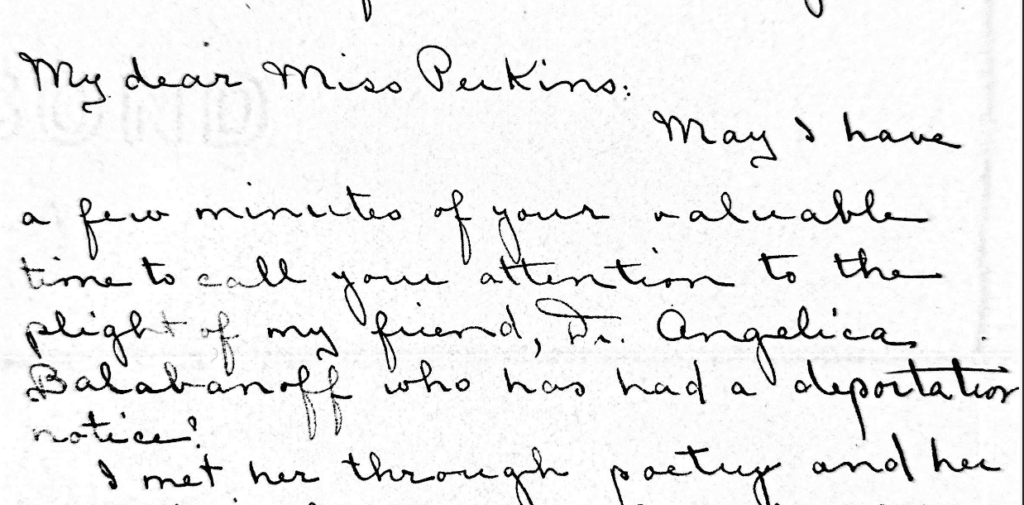

Angelica Balabanoff: Writer, 1939

A friend reached out to Perkins on behalf of Angelica Balabanoff, a Communist politician and writer from Russia. Despite an impeachment resolution against her for not deporting another alleged Communist, Perkins extended Balabanoff’s visitor visa until returning to Europe became safe after World War II. Balabanoff moved back to Italy, where she lived and wrote until 1965.

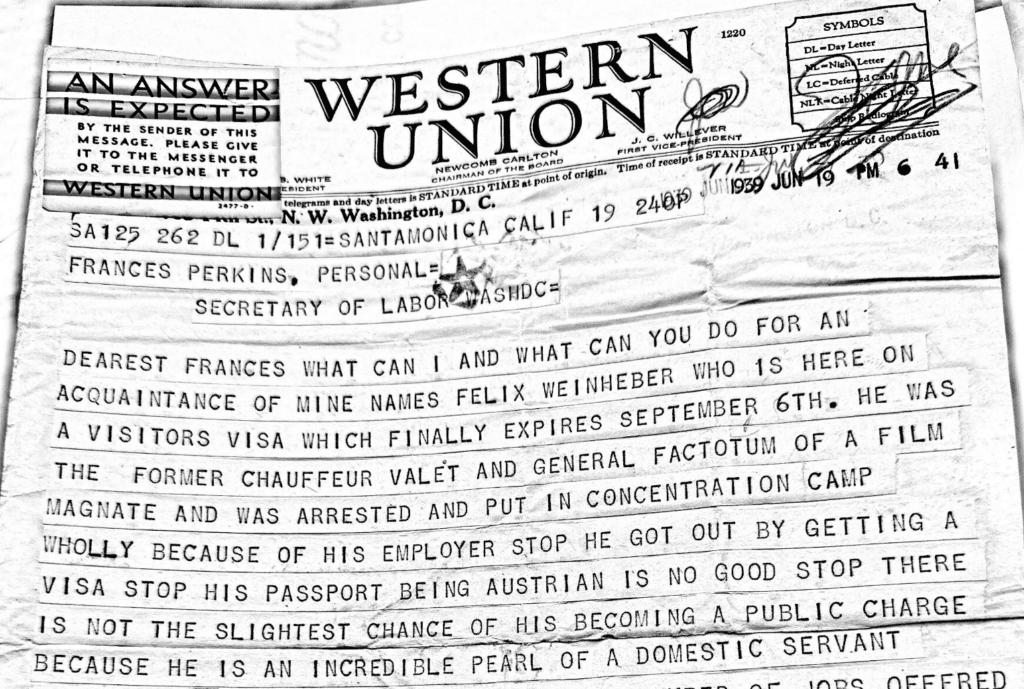

Felix Weinheber: “Incredible Pearl of a Domestic Servant,” 1939-1940

Perkins’s friend, journalist Dorothy Thompson, reached out to her on behalf of an Austrian man she knew in Los Angeles named Felix Weinheber. Together, Perkins and Thompson helped Weinheber navigate the immigration system to go to Mexico to obtain new paperwork until he was able to become a naturalized citizen.

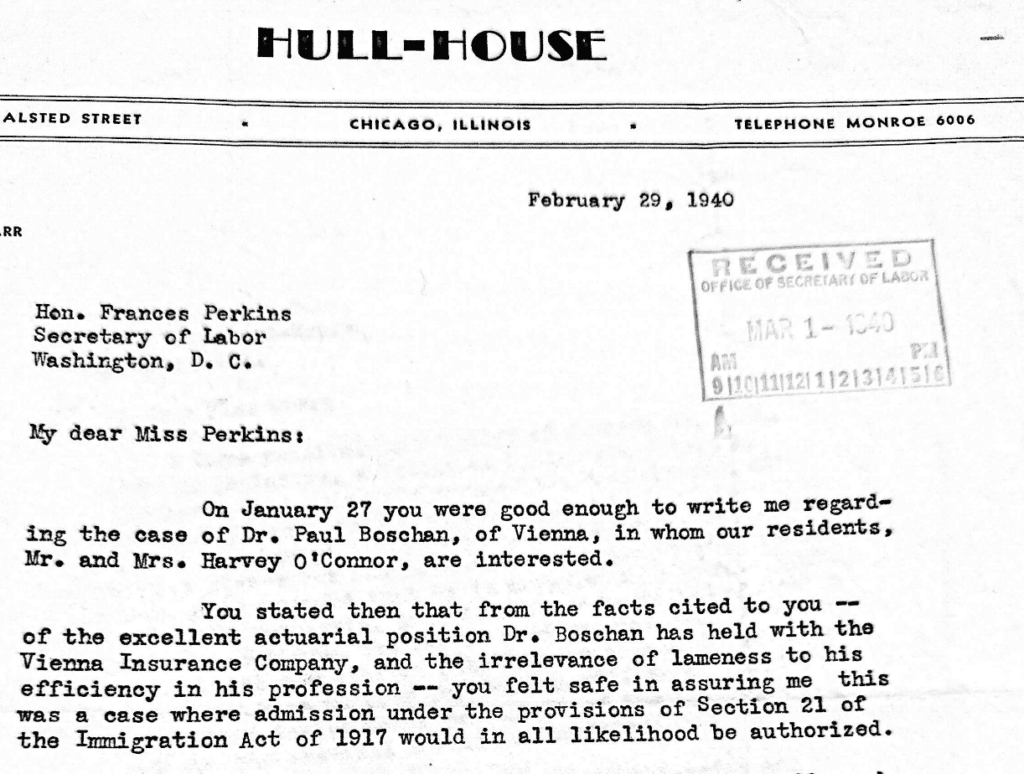

Dr. Paul Boschan: Insurance Worker, 1940

Charlotte Carr was the Director of Hull House, the famed Chicago settlement home where Perkins had volunteered as a young adult. Carr wrote to Perkins on behalf of Paul Boschan, a refugee from Nazi Germany with a physical disability. The Immigration Act of 1917 had aimed to prevent people with disabilities from entrance to the U.S. Perkins intervened in writing to permit Boschan to board the ship and to permit passage through Ellis Island. He found refuge in the U.S. because of her efforts.

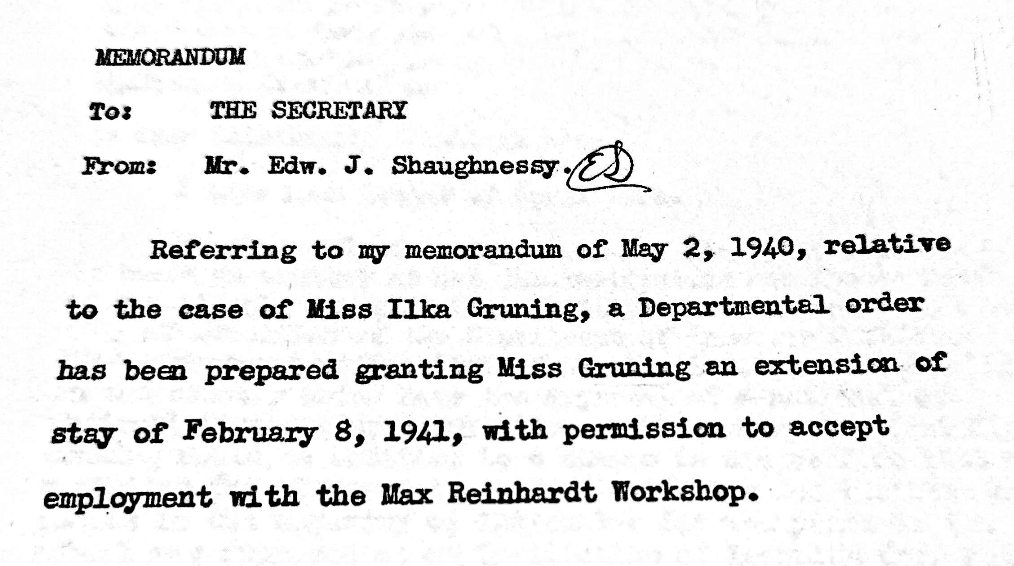

Ilka Gruning: Actress and Theater Teacher, 1940

A friend wrote to Perkins on behalf of refugee Ilka Gruning, a young professional in the theater industry. Gruning was “in tears off and on for months.” Because the theatre school was not accredited, which would have allowed Gruning to qualify for a non-quota visa, Perkins changed Gruning’s visitor visa to a temporary business visa, serving the same purpose to allow her to stay in the country.

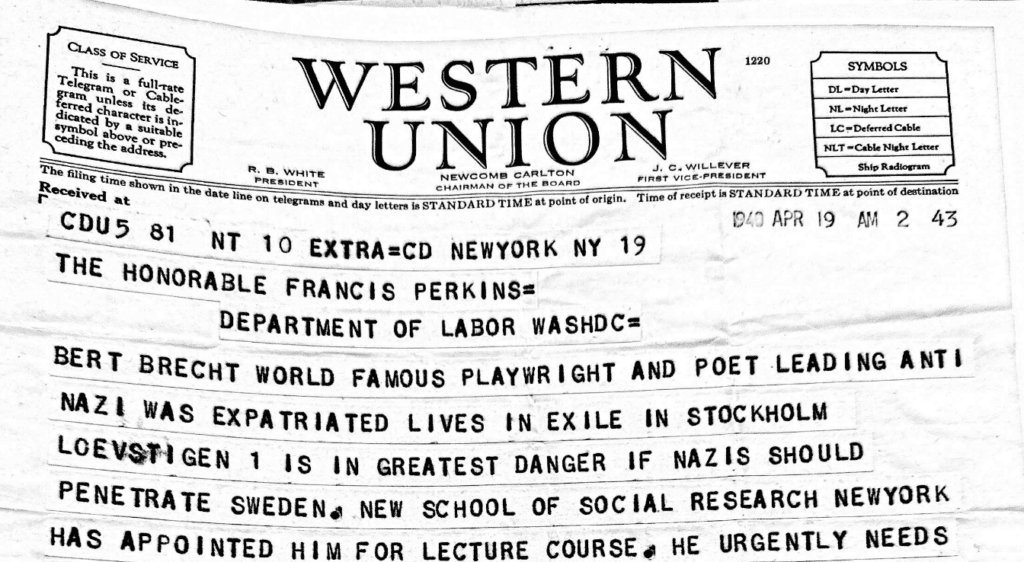

Bertolt Brecht: Dramatist, Playwright, and Poet, 1940

One of the most common attributes of modern State of the Union addresses is the “designated survivor,” or the Cabinet-level official who customarily forgoes attending the address for national security reasons. This is a relatively recent phenomenon that can only be traced back to 1984.

Foreign Affairs editor Hamilton Fish Armstrong wrote to Perkins on behalf of Bertolt Brecht, whose anti-Nazi art and writing made him a refugee. Acting on Perkins’s advice, Brecht and his family lived in the U.S. until the end of World War II, when they returned to Germany.

People wrote to Perkins on behalf of refugees not only because the INS was in the Labor Department from 1933 to 1940, but also because she established herself early in the Roosevelt administration as a foremost advocate for refugees. As explained in my book, her efforts included a legal battle against the State Department, a robust child refugee program, multiple legislative endeavors, and a series of visa extensions, through which she helped save approximately twelve to fifteen thousand lives. The last sentence of my book’s afterword explains: When they wrote “Dear Miss Perkins,” family and friends of refugees overseas did not know what would happen or if she would be able to solve their problems. They had good reason to believe that she would try.

Interested in learning more? You can join Dr. Rebecca Brenner Graham in person at the Archives or virtually in a conversation with historian Elizabeth Griffith about her new book next Thursday, March 27 at 6:00 p.m. EST. A book signing will follow the program.

Related Content

First Lady Delegate: Eleanor Roosevelt and the U.N.

Remembering President Jimmy Carter