First Steps Toward Independence

On Friday, we celebrated another lively July 4th at the National Archives. Each year, hundreds gather to hear our cavalcade of historical interpreters read the one and only Declaration of Independence at its home in the National Archives. This year was extra special as we commemorated the 250th anniversaries of the U.S. Army, Navy, and Marine Corps with performances and speakers representing those military branches.

Also for the first time, several key, rarely displayed documents went on public view in the Rotunda. Each of these documents tie into the moment when independence was declared. Altogether, these documents showcase the Declaration’s enduring legacy of liberty. Even if you were unable to make it to the museum this 4th, read on to learn more about these spectacular artifacts, with additional context courtesy of Jessie Kratz, historian at the National Archives.

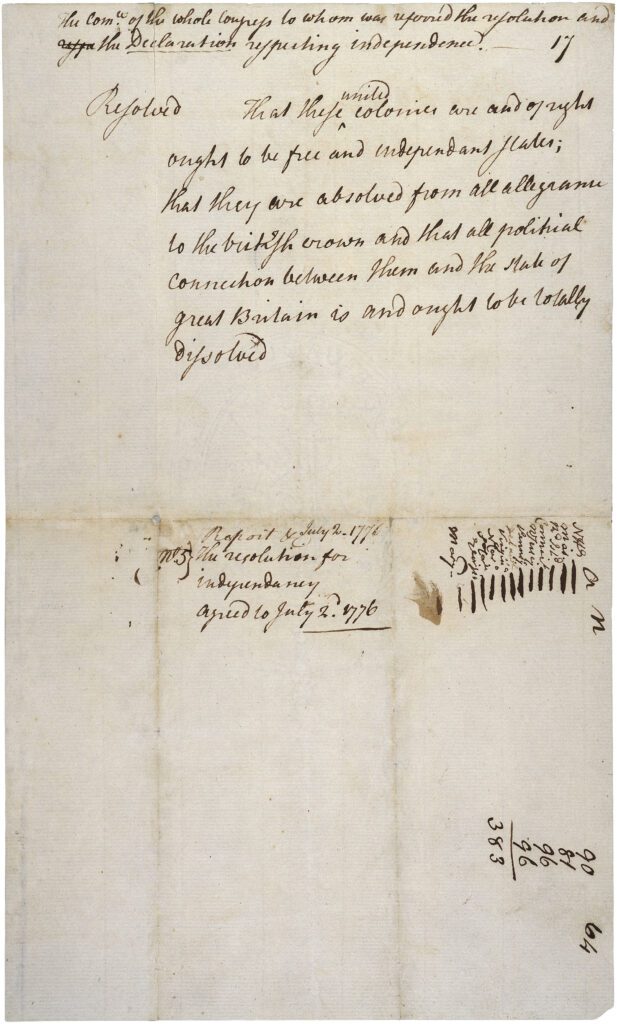

The Lee Resolution—June 7, 1776

The Lee Resolution for Independence, 1776

On June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia introduced a resolution “that these united colonies are and of right ought to be free and independent states.” Lee had already gained attention over a decade earlier for his staunch opposition to the Stamp Act of 1765, which unfairly taxed American colonists for paper imports. Lee is represented on the Barry Faulkner Declaration mural in the Rotunda, holding a sword.

Lee is depicted second from the right, wearing with the yellow coat

The Lee Resolution contains three parts. In addition to a declaration for independence, it also calls to form foreign alliances, which led to the alliance with France and a plan for confederation that led to the eventual drafting of the Articles of Confederation. The resolution essentially paved the pathway for the Declaration of Independence to be created.

Adoption of a Resolution Calling for Independence—July 2, 1776

On July 2, 1776, Congress approved the Lee Resolution and voted to declare independence. John Adams actually considered July 2 the definitive day of independence, even writing to his wife Abigail that “[t]he Second Day of July 1776, will be the most memorable Epocha.”

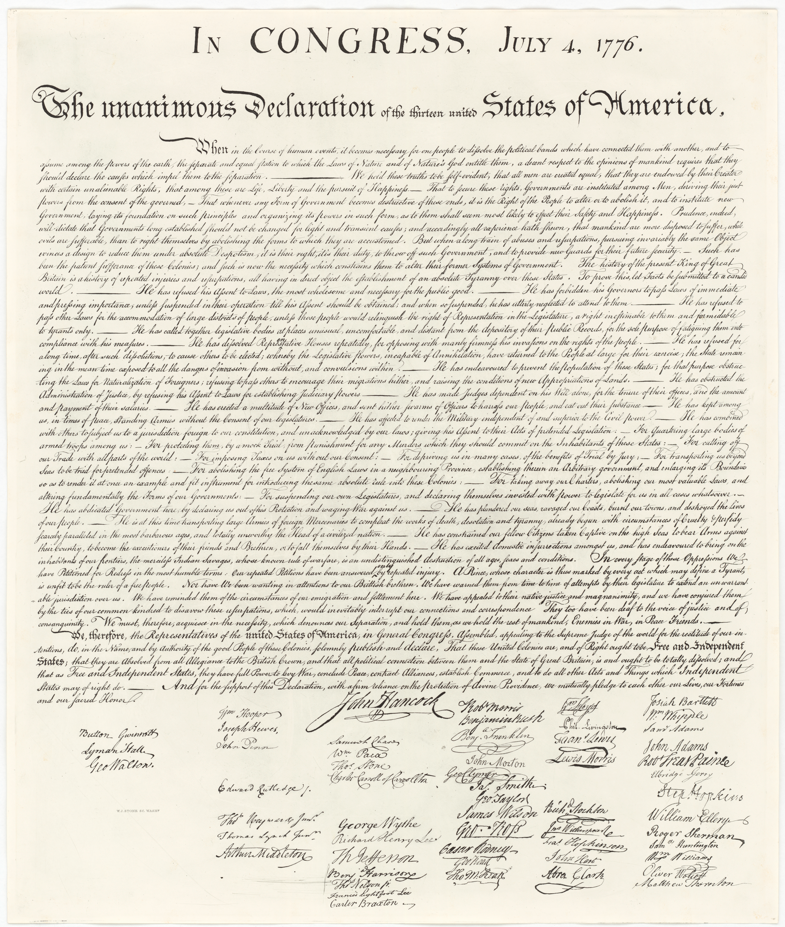

But it was two days later, on July 4, that the Continental Congress ratified the text of the Declaration, which is why we continue to celebrate on that date. As you might have already deduced, the Declaration of Independence on display in the National Archives Rotunda was not in fact signed on July 4, 1776. After New York approved the Declaration of Independence, thus making it unanimous, Congress ordered that a final handwritten document be prepared on parchment. Timothy Matlack, the assistant to the Secretary of Congress, was the penman. On August 2, the delegates began to sign it, with President of the Congress, John Hancock, being the inaugural signator. Delegates signed by state from north to south. Some delegates signed after August 2, with 56 delegates ultimately signing the document.

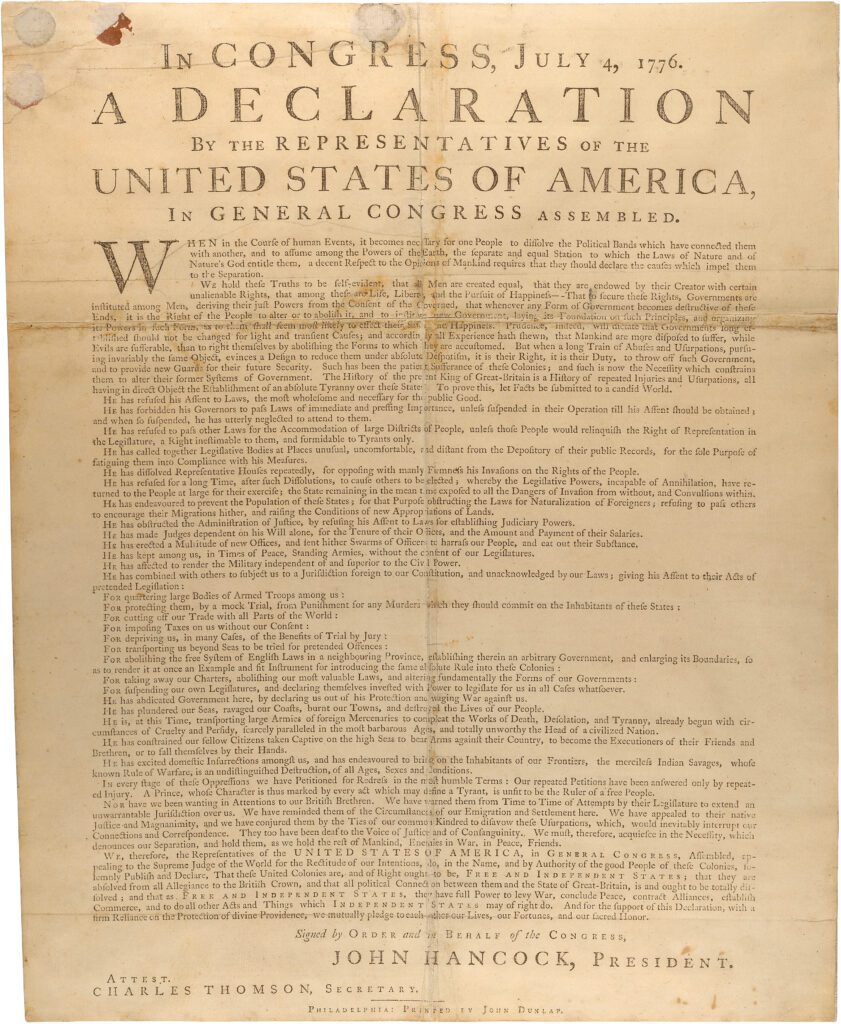

Dunlap Broadside of the Declaration of Independence—July 4-5, 1776

The Dunlap Broadsides, named for Philadelphia-based printer John Dunlap, were the earliest versions circulated among the colonies that showed the full text of the Declaration of Independence.

The text of the Dunlap Broadside differs from the final, engrossed version in the National Archives Rotunda. When Congress voted on the Lee Resolution on July 2, only 12 of the 13 colonies adopted it. New York did not vote. It wasn’t until July 9 that New York officially approved the Declaration of Independence, making it unanimous. While the engrossed Declaration of Independence begins with, “The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America,” the Dunlap Broadside of the Declaration says, “A Declaration By the Representatives of the United States of America, In General Congress Assembled.”

Two years after John Dunlap printed the first copy of the Declaration of Independence, he and his partner David Claypoole became the official printers for the Continental Congress. They also printed the Articles of Confederation and two draft copies and the final version of the Constitution. They had to sign oaths of secrecy to print the documents.

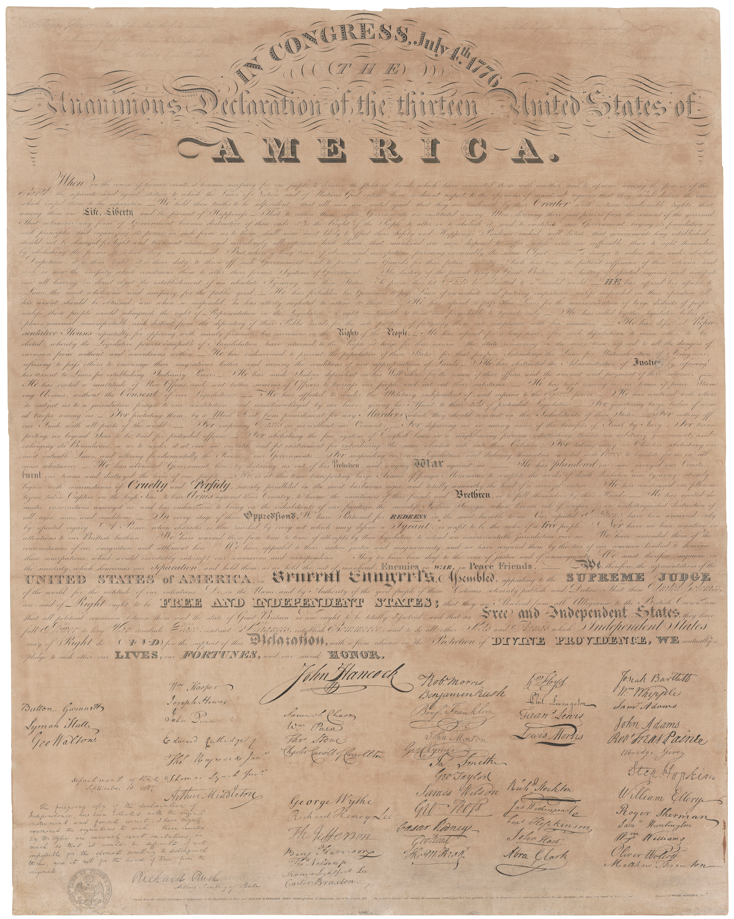

Tyler Engraving of the Declaration of Independence—1818

In 1818, publisher and engraver Benjamin Owen Tyler of the City of Washington published this ceremonial engraving of the Declaration. He dedicated it to the Declaration’s principal author, Thomas Jefferson, and included an attestation by the acting Secretary of State Richard Rush, son of signer Benjamin Rush, that it was a correct copy. The National Park Service estimates that Tyler produced 1,700 copies. The National Archives has this single copy.

Bicentennial Print of the Declaration of Independence from the Stone Engraving Plate— 1976

Prints of the Declaration of Independence were made from the Stone copperplate engraving during the 1976 Bicentennial celebrations. When the copperplate was transferred to the National Archives from the State Department, its printing face was covered with a layer of beeswax and paper. In 1976, at the request of the National Archives, master printer Angelo LoVecchio at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing removed the paper and wax. LoVecchio then inked the plate to make a very limited printing of seven impressions on paper. This was the first use of the engraving since the 1890s. One impression was given to the National Park Service for exhibition in Philadelphia for the Bicentennial, and the remaining impressions remained at the National Archives. There are 40 related photos in the catalog here.

Related Content