First Freed: D.C. Emancipation Day

The impact of the Emancipation Proclamation is undisputed, but did you know it was not the first major document that freed enslaved people? Today we celebrate 163 years of the D.C. Compensated Emancipation Act, the first “experiment” in emancipation in the United States. This important predecessor to the Emancipation Proclamation is significant not only as a stepping stone to freedom, but also as a powerful local symbol in its own right.

North or South?

Washington, D.C. was named the new capital under the Residence Act of 1790, a compromise between north and south bridged by George Washington, whose residence, Mount Vernon, was nearby. The original District was a diamond-shaped plot of land ceded by two slaveholding states, Maryland and Virginia.

Despite the “compromise” location, Washington D.C.’s position between two slave states meant the new capital also allowed for slavery. Almost immediately, enslaved African Americans were deployed to build structures like the White House and the U.S. Capitol, as well as to serve as maids and cooks. By 1800, over 3,500 enslaved people resided in the District.

Free and enslaved African Americans made up a large part of the District’s population from its very early days. One notable example was Benjamin Banneker, the free son of a former slave, who accompanied the original surveying team that established the boundaries of D.C. in 1791.

"Purchasing" Power

Well before full emancipation, a process known as manumission was one of the only ways freedom was granted in D.C. and other slave-holding states. Manumission is a certificate of freedom typically issued through a deed or the executed will of a deceased slave owner. In some limited cases, enslaved people earned wages and bought their freedom themselves.

The manumission records, or “freedom papers,” for the District are held in the National Archives in Record Group 21, Records of the Circuit Court for the District of Columbia. In the example below, William Heard was formally freed after he paid $50 upon the death of his owner, the late George Mahorney. Robert Mahorney, perhaps a relative, was the executor of George’s will.

No Compromise

The Compromise of 1850 was a turning point for the nation at a moment when the question of expanding slavery into western territories was reaching a boiling point. The compromise outlawed the sale of enslaved persons within the City of Washington, but it did not outright abolish slavery.

In fact, this compromise set up more robust fugitive slave enforcement at a time when many enslaved people from Maryland and Virginia were fleeing to the District, where the African American population was booming. The original Fugitive Slave Act, dated 1793, allowed slave owners to issue warrants requiring the capture of any escapees, even in free northern territories.

The fugitive slave cases for the District of Columbia are held in the National Archives Microfilm Publication M433, Fugitive slave case papers, 1851–63. While these warrants are not yet digitized, they are also a part of Record Group 21.

Emancipation at Last

During the Civil War, pro-abolition Senator Charles Sumner reminded President Lincoln that, as the head of the federal government, he was the largest slaveholder in the U.S.—referring directly to enslaved people of the District of Columbia.

By December 1861, the D.C. Compensated Emancipation Act was introduced in Congress, making its way to the President’s desk on April 16, 1862.

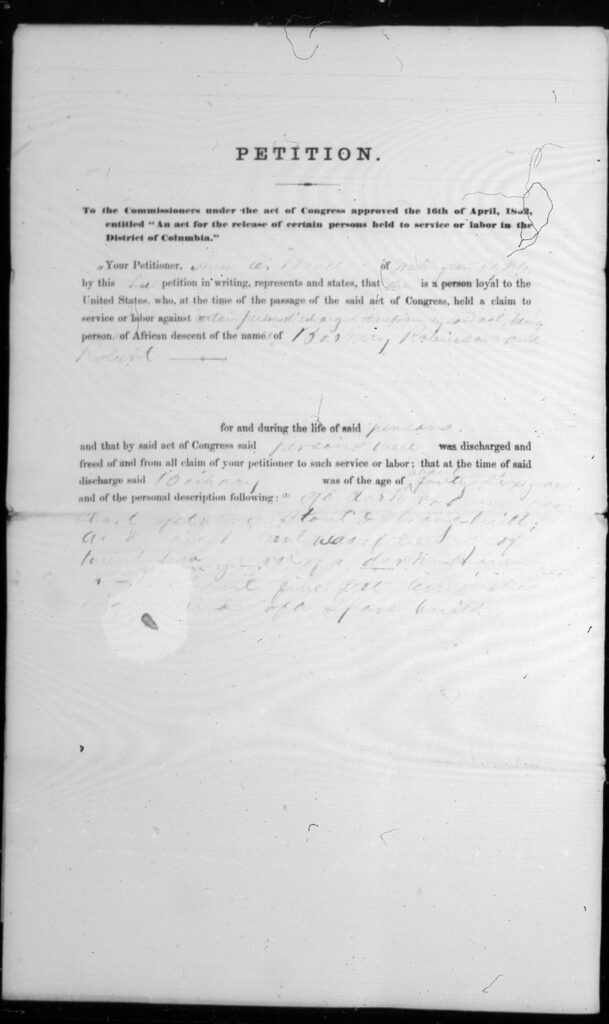

Under this law, slaveholders were eligible for compensation. The process required owners to file paperwork with a three-person, Presidentially appointed commission to receive their payment. One part of the act required that they pledge loyalty to the Union, which resulted in some owners never filing. Shortly after the initial bill's passage, a supplemental act followed that allowed enslaved persons to file their own petitions.

The original petitions can be found in the Records of the Board of Commissioners for the Emancipation of Slaves in D.C., Record Group 217.6.5. Nearly 1,100 of them are digitized here.

Petition of Anne E. Beall, 1862

These developments laid the groundwork for Lincoln’s eventual passage of the Emancipation Proclamation, which symbolically declared freedom for enslaved people in Confederate states. Although limited in immediate effect, it marked a turning point in the fight against slavery. Full abolition came with the 13th Amendment in December 1865, which ended slavery nationwide and fulfilled the promise first realized in the nation's capital.

To this day, Emancipation Day is celebrated annually in Washington, D.C. on April 16. Learn more about emancipation in D.C. in the museum's Records of Rights exhibition or online.

Join the Archives from June 20 to June 2024, 2025 to see the original Emancipation Proclamation and General Order No. 3 on display.

Related Content