Eye Spy with My Little Eye

If there’s one thing we know about the Internet as a community, it’s that we use humor to make sense of the world. So when in January 2023, Americans looked up in the sky and saw something unfamiliar, the Internet was abuzz. This included the U.S. military, which released perhaps the most online reaction of all: a selfie taken by a U.S. airman 70,000 feet in the air with the unidentified flying object. It’s known as “legendary” around the Pentagon.

Here’s another way to make sense of the world: history. Now that the objects have been identified as Chinese spy balloons, we can look back at the history of balloons and learn about how and why they’ve been used in the past.

Maybe it will help us make sense of the future.

The selfie in question: A U.S. Air Force pilot with a suspected Chinese surveillance balloon. Photo taken somewhere over the Midwest. February 3, 2023. Courtesy of the Department of Defense

In this issue

The Chinese spy balloon that President Joe Biden ordered the U.S. military to shoot down on Saturday, February 4…

During World War I, both the Germans and the Allies used observation balloons extensively…

The 555th Parachute Infantry Company, an all-Black unit trained in smoke-jumping, fire suppression, and recovery and destruction of the Japanese balloon bombs…

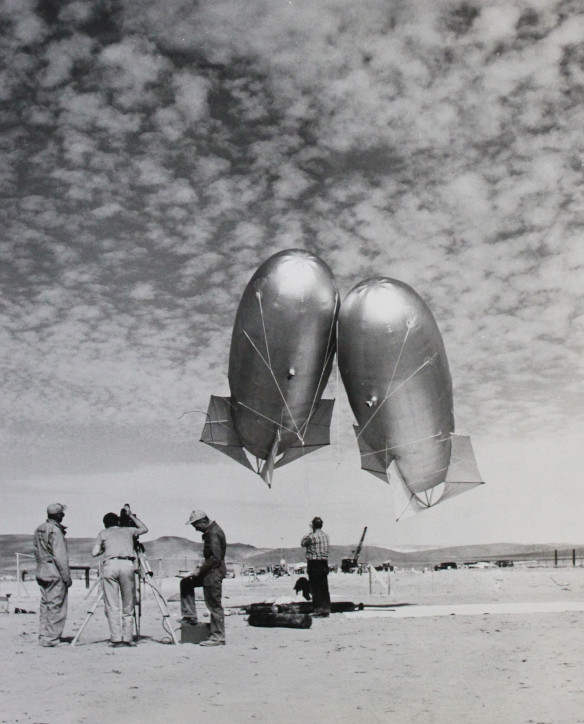

History Snack

Up, Up, and Away

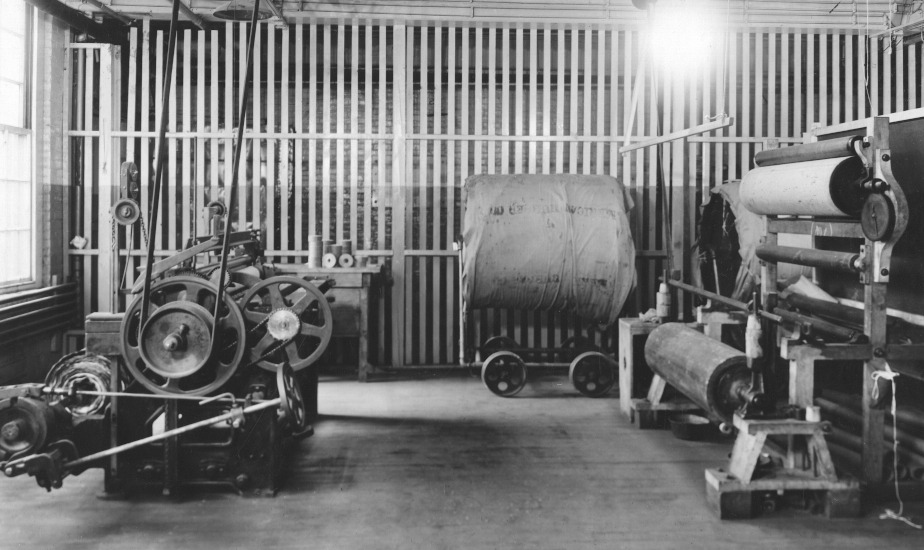

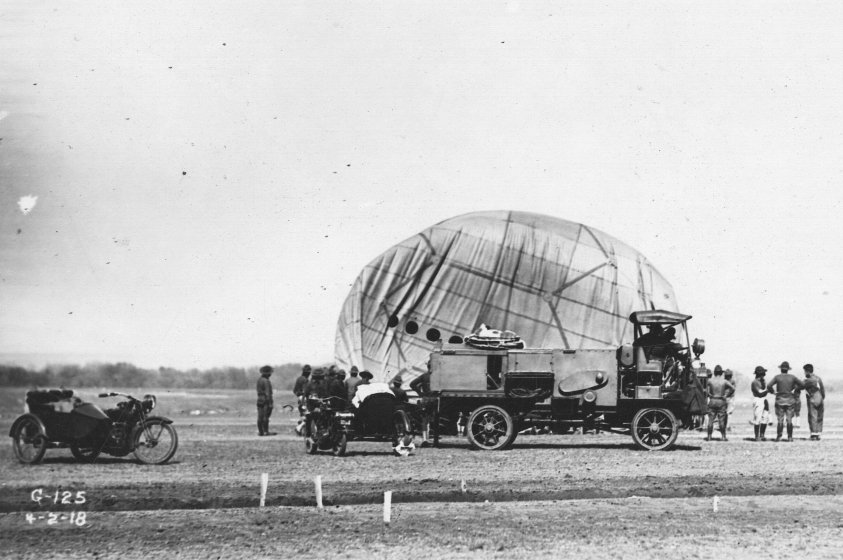

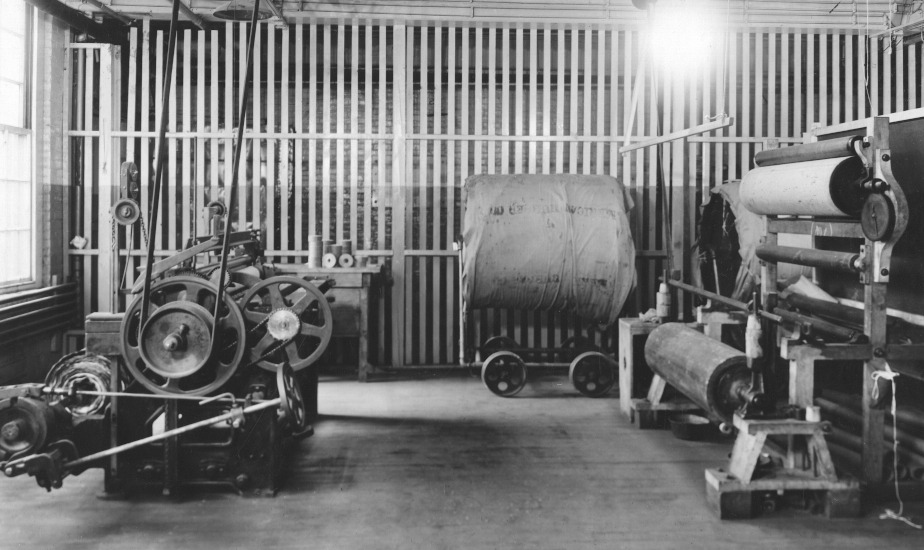

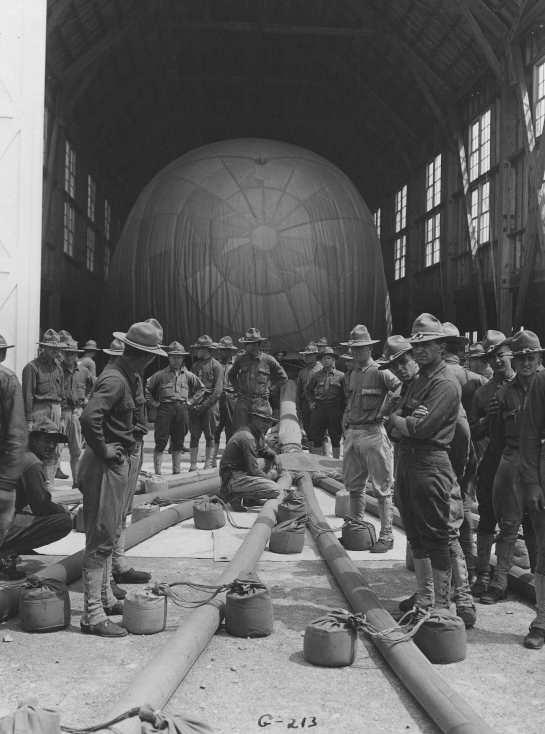

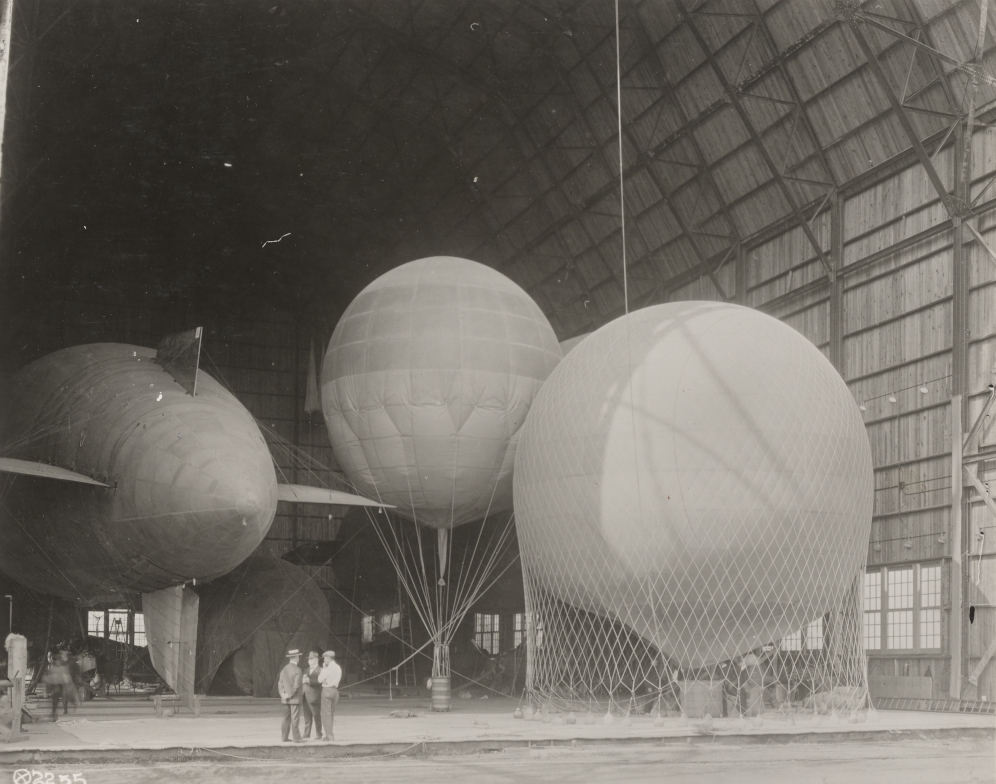

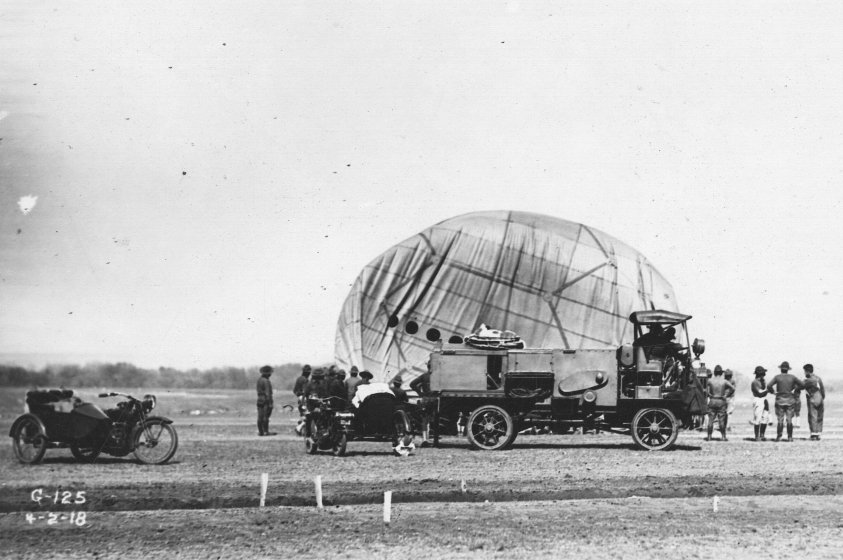

Federal observation balloon being inflated

National Archives Identifier: 525085

The Chinese spy balloon that President Joe Biden ordered the U.S. military to shoot down on Saturday, February 4, had entered U.S. airspace on January 28, floated into Canadian airspace on January 30, and then wafted its leisurely way back over the U.S. a day later, flying at between 60,000 and 65,000 feet over several military installations and nuclear missile silos and causing ground stops at airports in its path all across the country.

A lot of the stuff that’s flying around over our heads is pretty harmless. As Dan Zak pointed out in the Washington Post on February 17, “The sky is full of stuff. . . . police helicopters, prop planes, ravens and starlings and eagles, runaway pink and blue latex balloons from gender-reveal parties. An average of 45,000 flights traverse American airspace daily, with 5,400 aircraft in the sky at peak operational times. Every day the National Weather Service launches about 180 balloons to collect data, sometimes from as high as 20 miles up. Higher still, approximately 23,000 pieces of debris larger than a softball orbit the Earth, along with 500,000 marble-sized objects, plus more than 5,000 working satellites. At lower altitudes: at least a million recreational drones, hovering over your neighbor’s backyard barbecue or at the wedding reception down the street. Some of the stuff in the sky is immediately identifiable, some less so. The alien craft that crashed in rural Colombia in 2017 and freaked out farmers? An internet balloon designed to boost WiFi signals.”

1874 patent for high altitude balloons

National Archives Identifier: 245163953

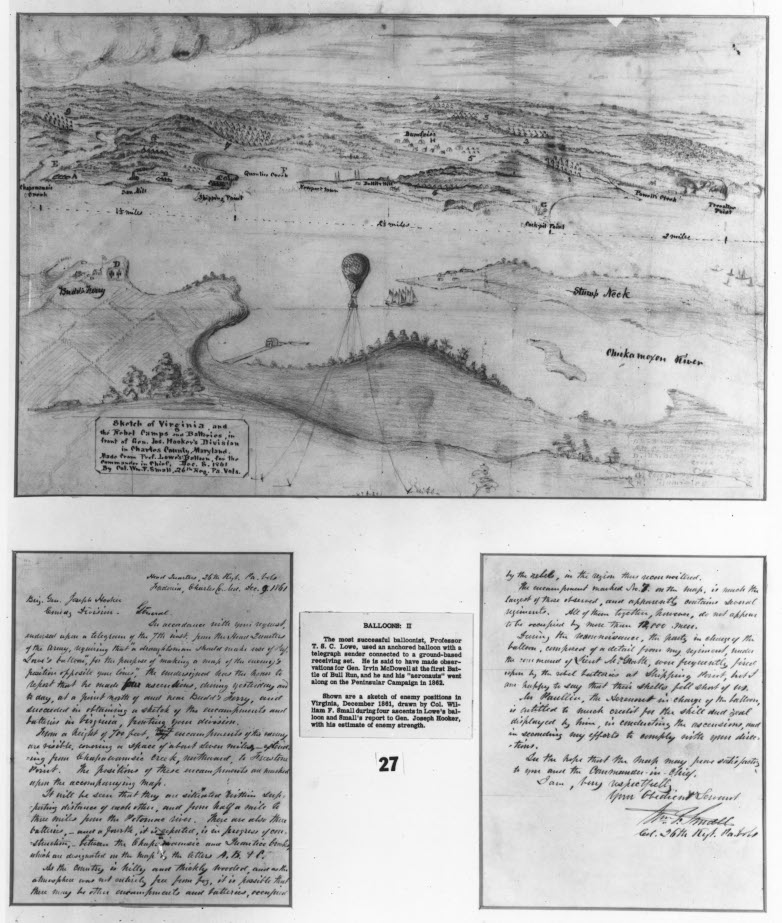

Spy balloons have a long and storied history. They were first used for gathering intelligence and locating enemy artillery during the French Revolutionary Wars, a series of conflicts France fought with other European nations between 1792 and 1802. Up until World War II, observation balloons were inflated with hydrogen gas, which was highly flammable. During the American Civil War, each side used balloons to spy on the other, although the Union Army’s efforts were much more effective than the Confederate Army’s were.

In particular, Thaddeus S. C. Lowe, who was a scientist, aeronaut and inventor prior to the war, devoted himself to building observation balloons for the Union that were much sturdier than the average balloon. In the run-up to the Civil War, Lowe was making test flights in preparation for a trans-Atlantic balloon flight, but when the conflict derailed that ambition, he offered his services to the Union effort. His first flight was at the First Battle of Bull Run, during which he surveyed the Confederate positions. His actions attracted the attention of Abraham Lincoln, who appointed Lowe Chief Aeronaut of the Union Army Balloon Corps in July 1861.

Civil War Spy balloons

National Archives Identifier: 74226946

The two sides used observation balloons mostly in the eastern theaters, although on occasion they also used them over the Mississippi River. Neither side ever succeeded in shooting down any of the other’s balloons—the aircrafts could easily reach altitudes of 1,000 feet or more, which put them well above the reach of artillery shells. Lowe in particular liked his balloons to be brightly colored and highly decorated. His balloon The Intrepid, for instance, featured an image of an eagle holding General George McClellan’s portrait in its beak—Lowe thought seeing that soaring overhead would upset the Confederate troops.

Lowe commanded the Union Army Balloon Corps until May 1863, but the corps was a civilian operation, and Lowe repeatedly clashed with the military men he had to cooperate with. Upon his resignation, James and Ezra Allen, two brothers who were Lowe’s best aeronauts, took the corps over, but the corps was disbanded by August of that year.

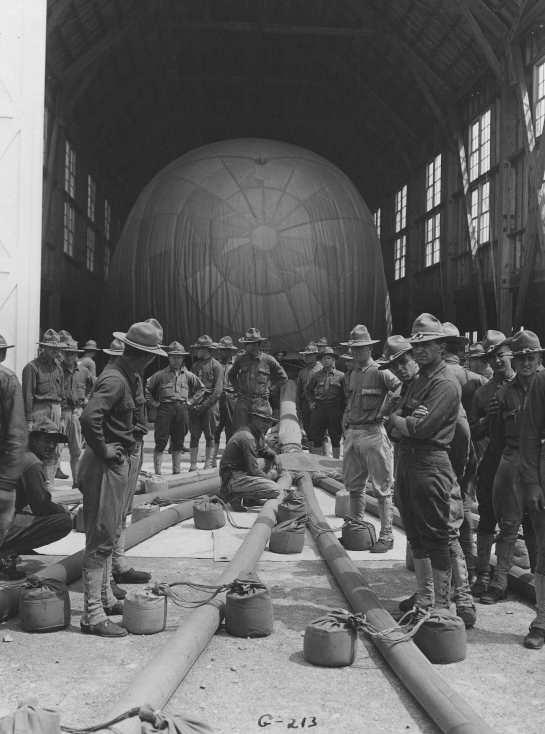

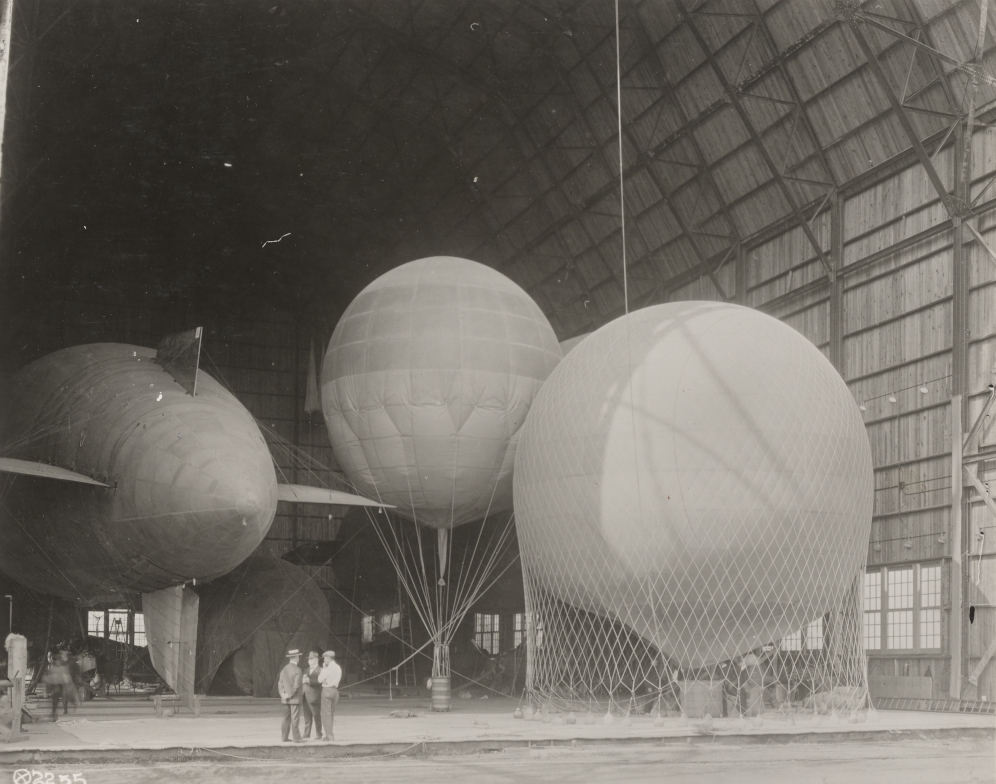

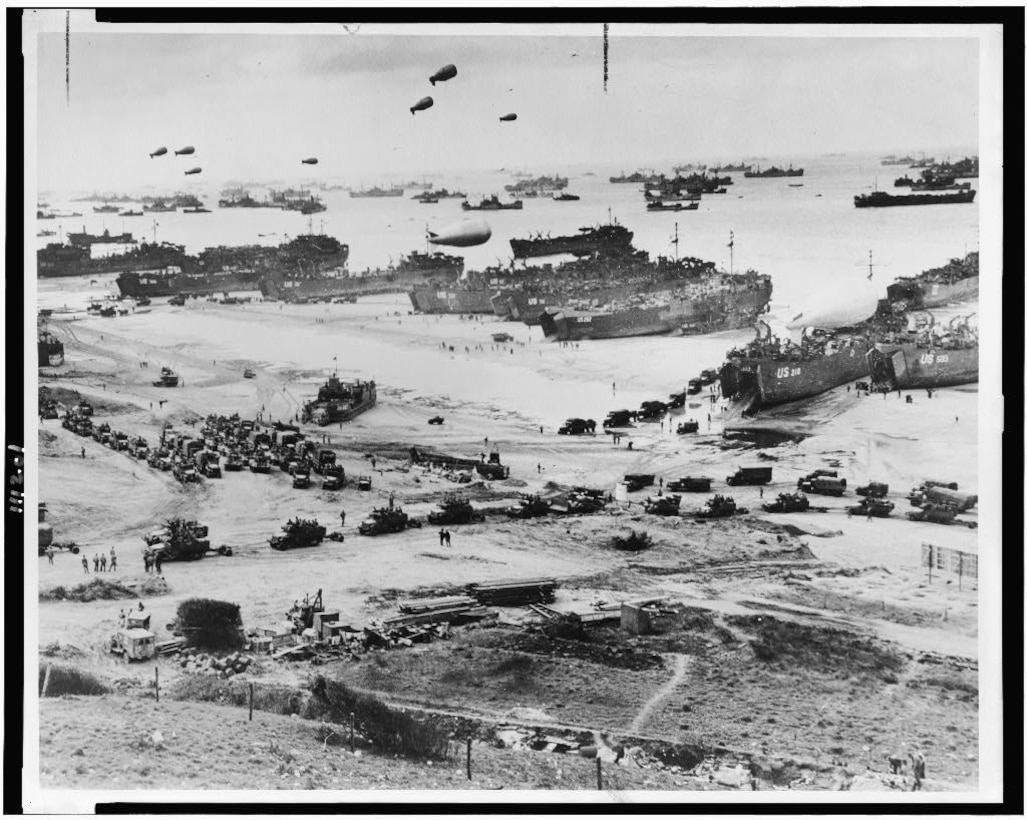

Inflated Purpose

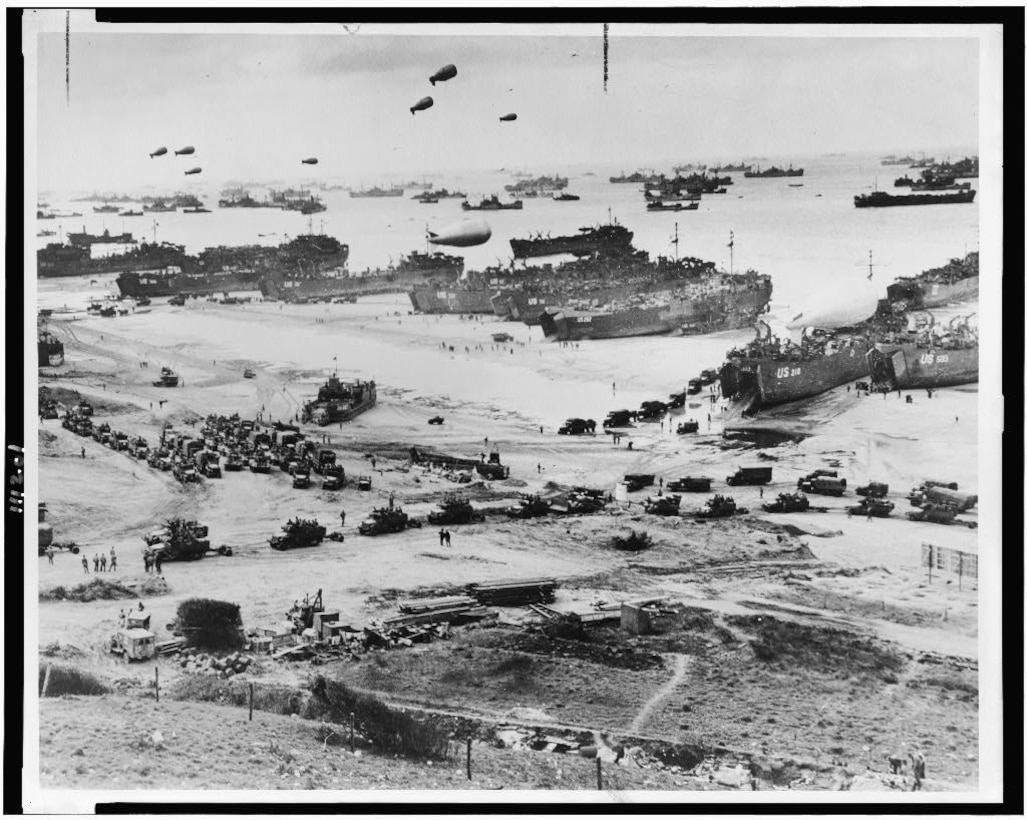

During World War I, both the Germans and the Allies used observation balloons extensively, flying them just behind the front lines and at altitude, to help direct artillery fire. The range and accuracy of artillery had greatly improved and could now shoot much further. The observers in the balloons communicated with the units on the ground via telephone. The balloons were equipped with anti-aircraft machine guns to defend themselves from enemy flyers who wanted to shoot them out of the sky, and the balloonists wore parachutes in case they were forced to bail out. The hydrogen used to inflate the balloons made it imperative for the balloonists to get away from their aircraft if they were under attack because the balloons would burst into flames if they were hit with gunfire.

Another innovation that developed during the war was dirigibles, larger balloons with light fabric skins stretched over wooden or metal frameworks, powered by engines and steered by propellers. As soon as they arrived on the scene, they had an immediate effect because they could move much more accurately over the landscape than the free or tethered balloons that had preceded them. They were used extensively for mapping enemy positions on the battlefield. They weren’t fast, though, which made them easy targets for enemy airplanes.

During World War I, 35 American balloon companies operated in France. They made 5,866 ascents totaling 6,832 hours in the air. In all, observation balloons were attacked 89 times. Some 35 were burned and 123 were shot down, but somewhat surprisingly, only one floated into enemy territory.

By the late 1930s, aeronauts increasingly used helium to inflate their balloons because it was much less flammable than hydrogen.

Spy balloon newsreel

(9 minutes 40 seconds, NO SOUND)

National Archives Identifier: 24979, page 13

The Fireflies

General Order No. 9, pg2 outlining the 555th mission

Source: NARA’s Text Message blog

General Order No. 9, pg1 outlining the 555th mission

Source: NARA’s Text Message blog

Combined civilian and military casualties during World War II were enormous. Great Britain saw over 450,000, Germany between 6 and 8 million, Japan 2.6 million, France over half a million, and some estimates of the Soviet Union reach as high as 24 million. Overseas, 418,500 soldiers and civilians gave their lives. But on U.S. soil? Seven casualties. Yes, you read that right.

During the war, Japan launched almost 10,000 spy balloons, each one carrying two incendiary bombs and an anti-personnel bomb, over the Pacific between November 3, 1944, and April 1945. The intent was to cause mass damage and wreak havoc on America’s west coast by destroying property and setting forest fires. Only about 300 ever reached U.S. soil, and luckily, they did not do much damage. But the U.S. military was prepared anyway, forming the 555th Parachute Infantry Company, an all-Black unit trained in smoke-jumping, fire suppression, and recovery and destruction of the Japanese balloon bombs. The operations were nicknamed “Project Firefly.”

16 soldiers who were paratroopers in the 555th at Fort Benning

Source: NARA’s Text Message blog

The unit worked in conjunction with the U.S. Forest Service and in total completed 36 missions and 1,255 jumps. Between 1944-1946, 191 paper balloons and three rubberized-silk balloons were found in the U.S., Canada, Alaska, Mexico and the Pacific Ocean. Eighty-nine other foreign fragments were recovered, but they were incomplete and not counted as balloons. The 555th suffered one casualty, a medic who died in an accident on August 9, 1945.

EO 9981 Desegregating the Military

National Archives Identifier: 300009

To avoid mass panic and providing information to the Japanese, the U.S. and Canadian press cooperated with the Army through the U.S. Office of Censorship in a voluntary press blackout regarding the balloons. At times, the members of the 555th themselves were not always looped in on the specifics of their mission.

Despite their heroism, the 555th were subject to racism and unequal treatment by the military. They often found themselves without adequate shelter, provisions and food. The U.S. military was not desegregated until Harry Truman issued an executive order in 1948.

The other six casualties on U.S. soil? A group of folks going on a picnic in Oregon. They came upon a balloon bomb in the woods, and while they were dragging it out, it exploded. Because of the previous press blackout, they didn’t know what they were handling was dangerous. But after this incident, the U.S. government highly publicized the existence of the balloons. These were the only six fatalities on U.S. soil during the war that directly resulted from enemy activities.

Training exercises of the 555th

(3 minutes 30 seconds, NO SOUND)

Source: NARA’s YouTube channel

Cold War, Hot Air

Read more about post-WWII surveillance in Ike and his Spies in the Sky

Source: NARA’s Prologue Magazine

Balloons were less useful for intelligence gathering in World War II because ground artillery and fighter planes had developed to the point at which they could shoot them down much more effectively, so the Allies resorted to using them mostly to drop propaganda leaflets in territories held by the Axis powers. Once the war in Europe ended, the U.S. also dropped leaflets over Japan in the hope of persuading the Japanese civilians to help end the fighting sooner.

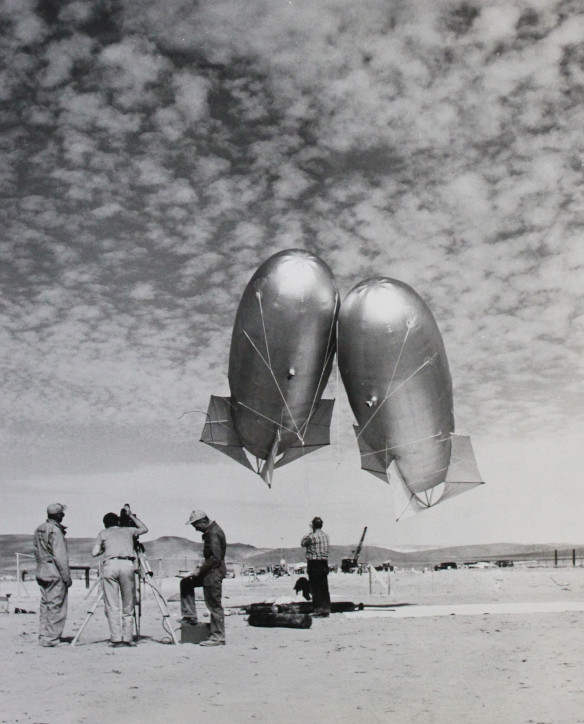

After the war, the U.S. Air Force initiated a spy balloon program in 1953 that President Dwight D. Eisenhower reluctantly approved that involved flying camera-equipped balloons over Soviet-controlled countries for surveillance purposes. The program yielded practically no useful information, but it did succeed in angering the Soviets. Eisenhower called a halt to the program in 1956.

Barrage Balloons, 1941

(15 minutes 17 seconds)

National Archives Identifier: 24418

View this profile on InstagramNational Archives Foundation (@archivesfdn) • Instagram photos and videos