It’s Classified. I could tell you but…

When we are giving tours of the National Archives Museum, some guests are bold enough to ask two burning questions: What can you tell us about Area 51? And is it the Archives at the end of the Raiders of the Lost Ark movie?

Thanks to popular movies and the endless fads of conspiracy theories, it’s easy to wonder about secret records. All the government’s cloak and dagger documents from the NSA, FBI, CIA, DOJ, NSC, DOD and other agencies are held in the Archives, but many are…well, classified.

The National Archives runs the government’s National Declassification Center. Its mission is “to advance the declassification and public release of historically valuable permanent records while maintaining national security.” As you would suspect, there’s a rigorous process for making such documents available, and the archivists who steward these documents work with the agencies or the office of the President to declassify them so the public and media can access them.

This week, we are taking a closer look at some of the most sought-after documents released by the NDC while learning about other secrets held in the Archives. Read on, un-redacted.

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

P.S. Craving more secret knowledge? Register for our special online event, Spycraft, a conversation with former CIA agent Robert Wallace.

November 22, 1963

Read the entire Warren Report

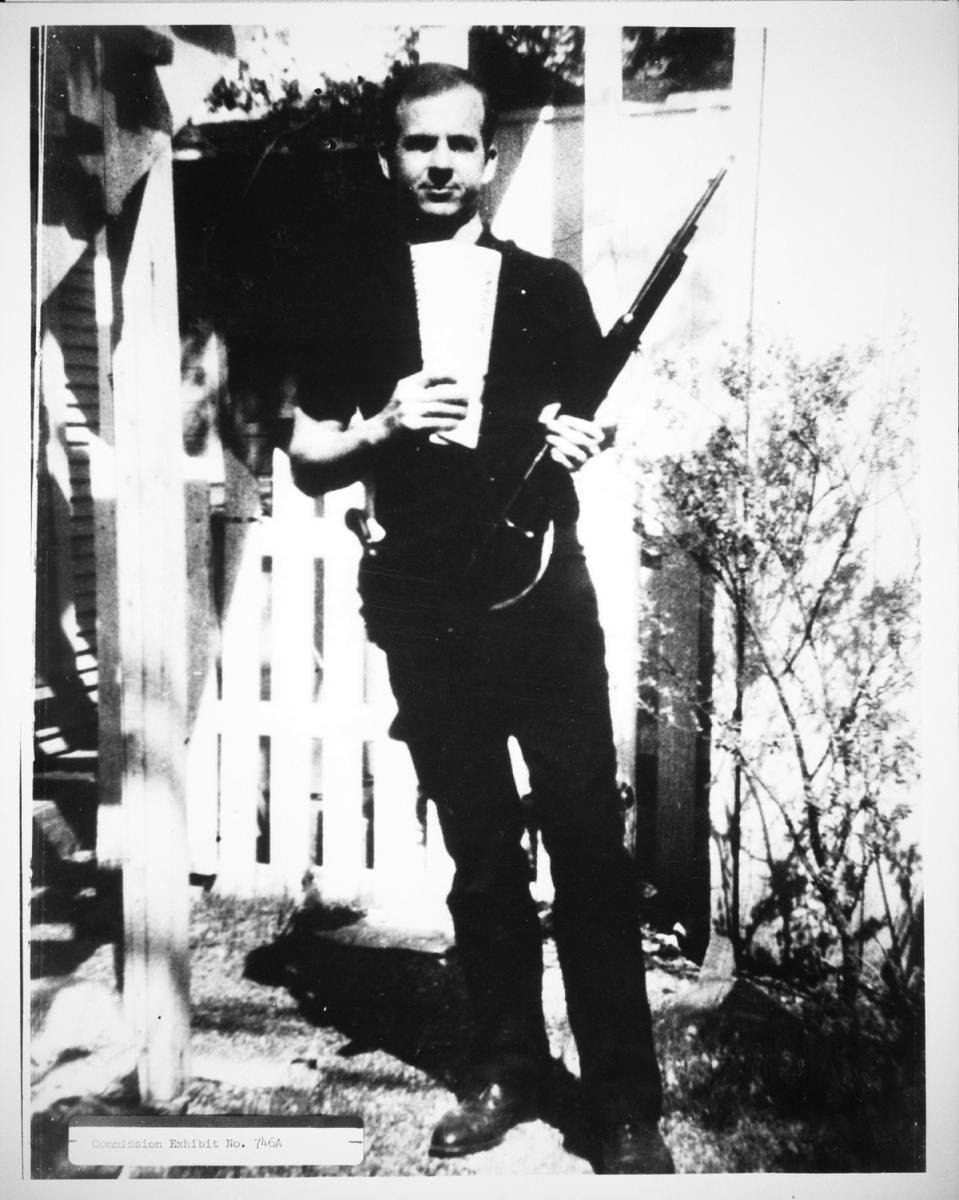

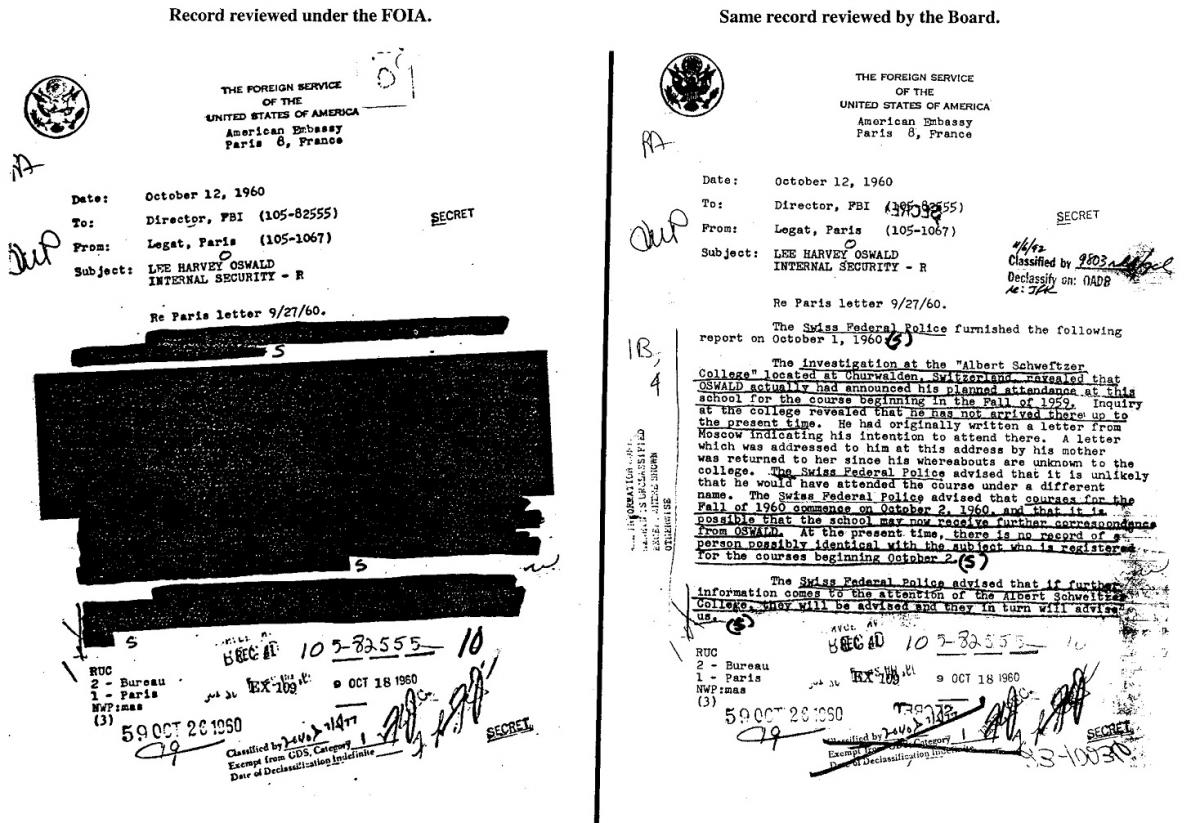

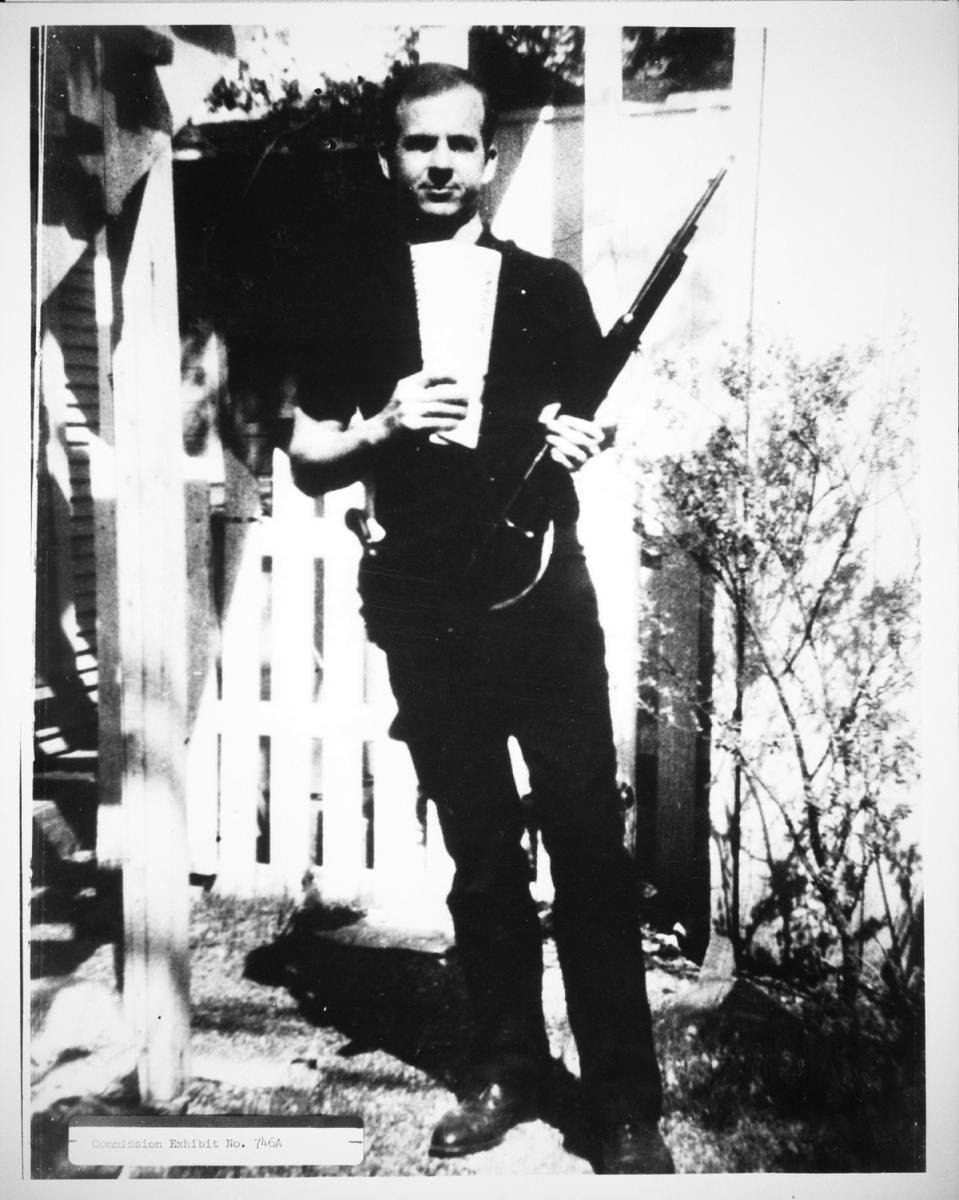

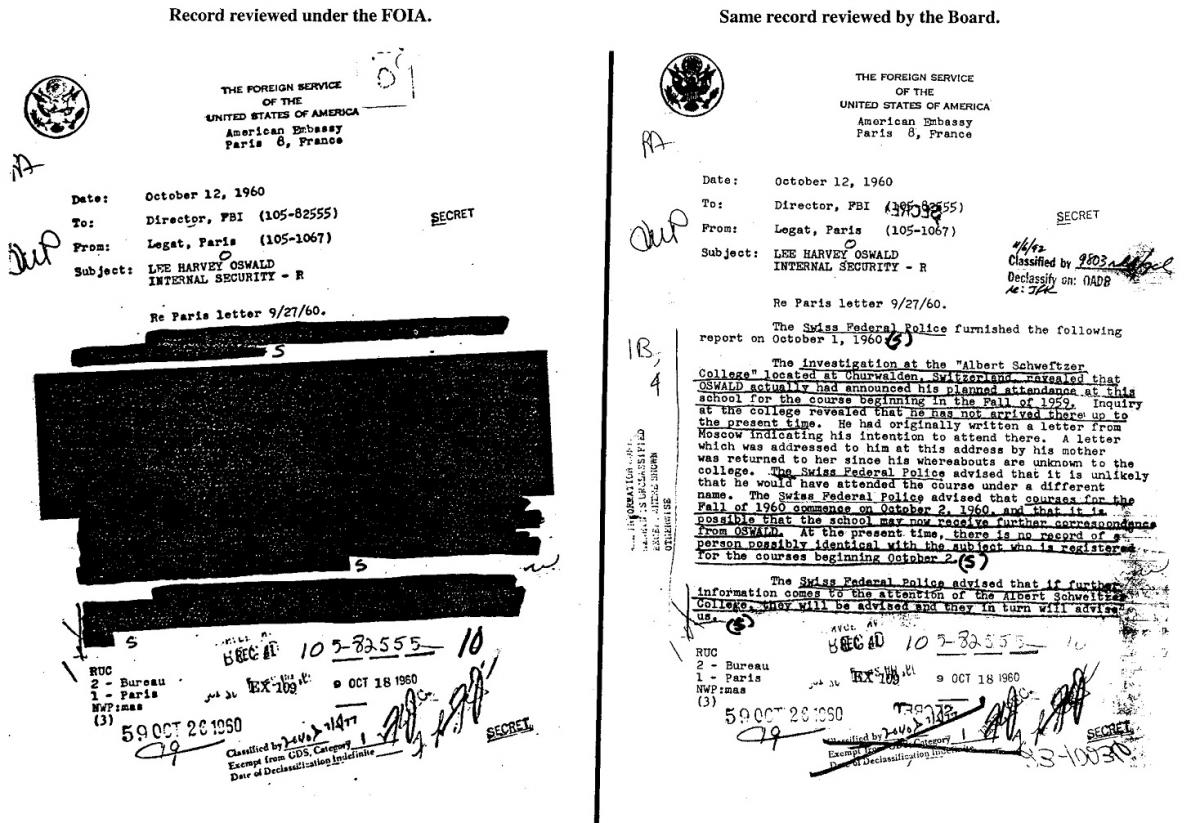

On December 30, 2009, then-Archivist of the United States David S. Ferriero established the National Declassification Center by executive order. Without the President John F. Kennedy Assassination Act of 1992 (the JFK Act), congressional records about the JFK assassination could not have been disclosed to the public until 2029. The JFK Act outlined provisions for transferring records to the Archivist, immediate public disclosure of the majority of records, and establishment of an Assassination Records Review Board to continually release records to the public at appropriate times. The JFK Act also created the JFK Collection, a group of records solely related to the President’s assassination.

As of 1998, 88 percent of the JFK assassination records had been made available to the public. This past December, the center released another 1,491 documents pertaining to the assassination of the president. These documents are now part of the John F. Kennedy Assassination Records Collection in the National Archives, which now contains approximately five million pages of records. Many of these resources are digitized and available online.

To view the text of a document or the full image, click on the image displayed above

Are we alone?

Saucers over DC comic

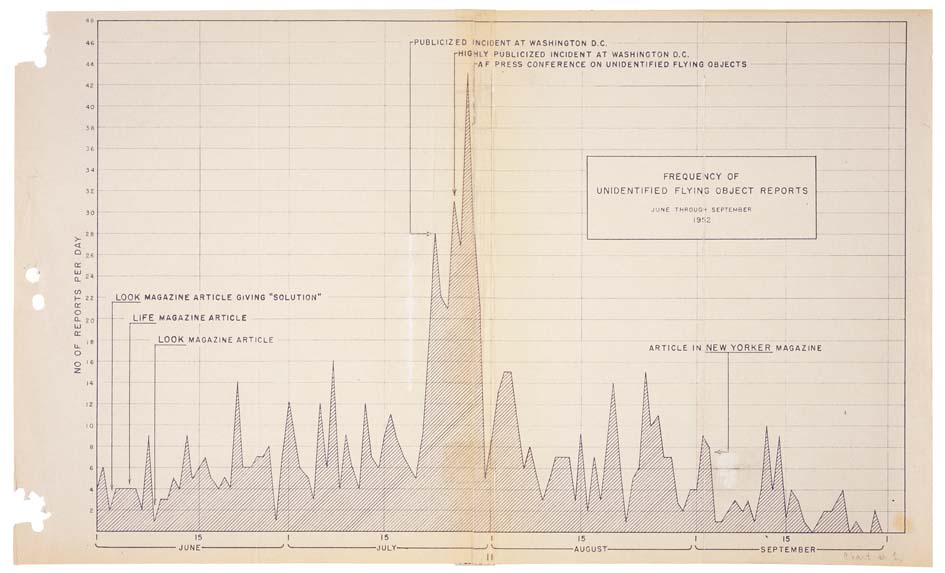

Roswell, Area 51, and other mysterious places – we could write an entire newsletter about materials about UFOs in the Archives. Between 1947 and 1969, the United States Air Force investigated 12,618 unidentified flying objects. The study, titled Project Blue Book, eventually accounted for all but 701 of these sightings, many of which have our modern-day images of aliens and their aircrafts: flying saucers and flying disks are consistently used to describe sightings. Members of the public, commercial airline pilots, and even military personnel reported sightings.

Roswell Daily Record, July 9, 1947

Frequency of UFO reports

The Air Force closed Project Blue Book in 1969, and the declassified documents now reside in the National Archives, as do several other collections of materials pertaining to unidentified flying objects.

The case files and administrative records of Project Blue Book can be viewed on microfilm in the National Archives Microfilm Reading Room at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland. The Motion Picture & Sound & Video Branch and the Still Picture Branch have sound recordings, some still pictures, and motion pictures. Finally, a Project Blue Book webpage provides online access to more than 50,000 U.S. government documents relating to UFOs.

(4 minutes 59 seconds)

Source: NARA YouTube Channel

Breaking and Entering

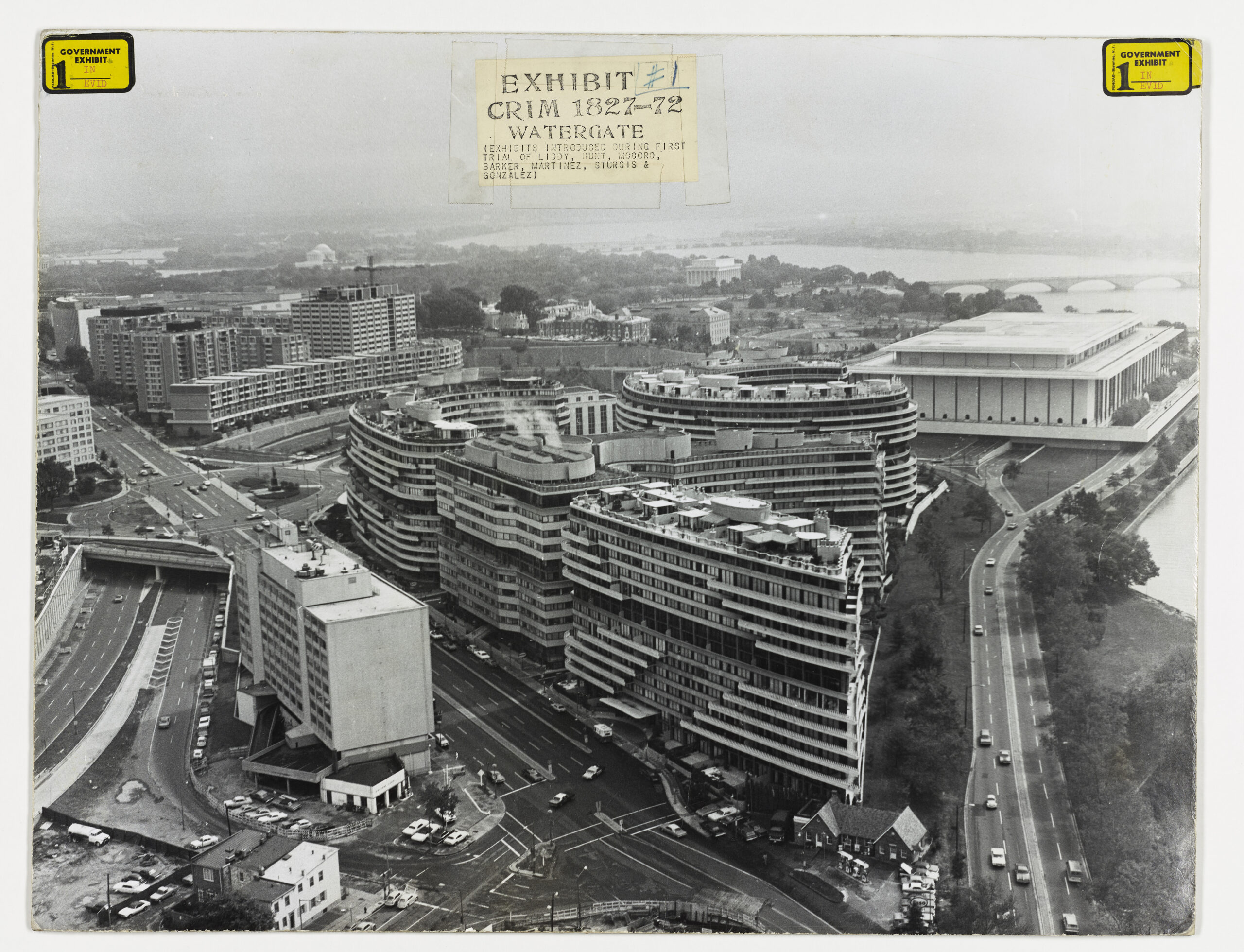

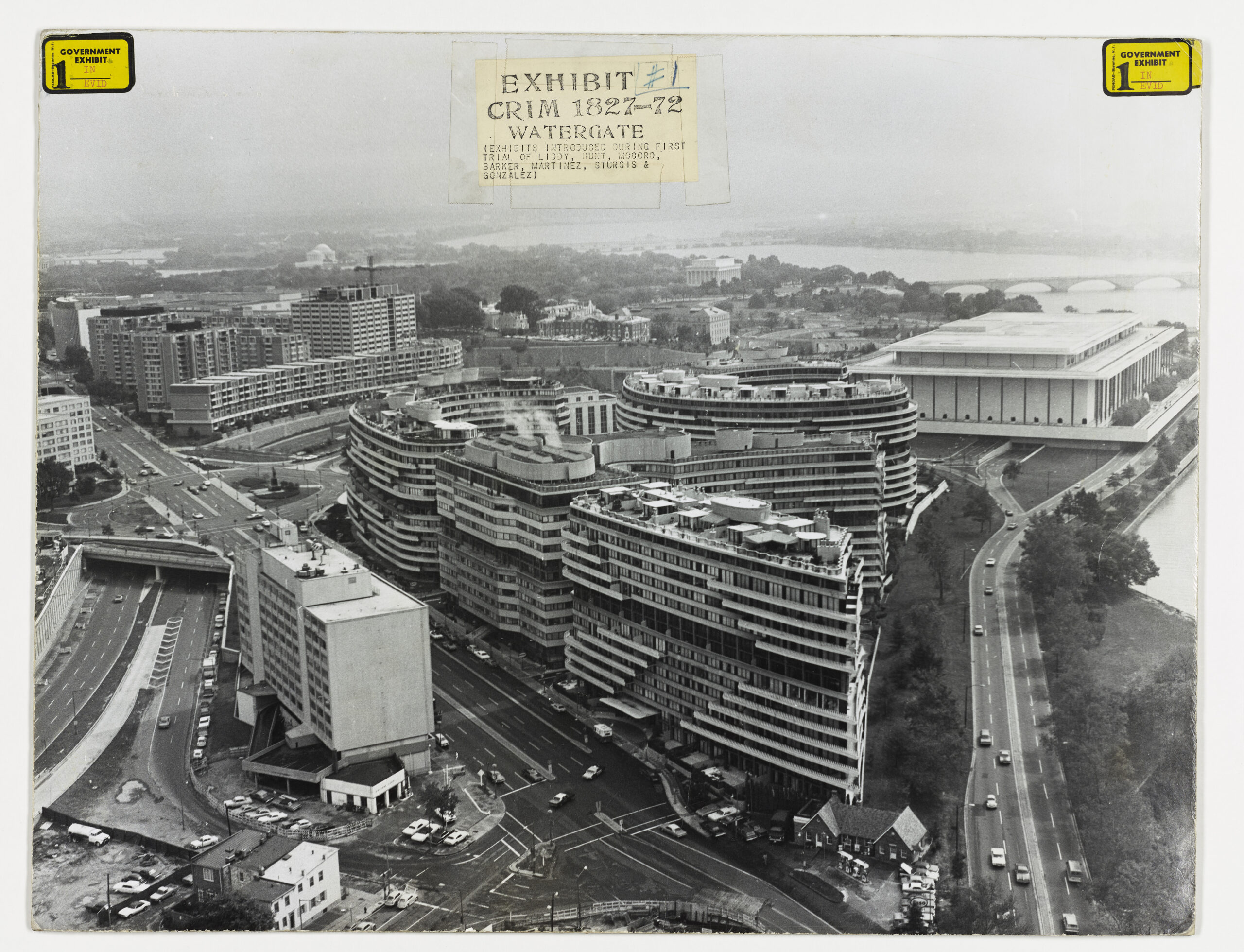

American politics ceased to be the same after the Watergate scandal. The (aptly named) Committee to Re-Elect the President (CREEP) broke into the Democratic National Committee’s headquarters on June 17, 1972, in an attempt to gain an advantage in the upcoming November election. And although many of us know the story of Watergate, the Archives’ holdings have also preserved the events of the aftermath.

Watergate Exhibit

Source: Ford Library

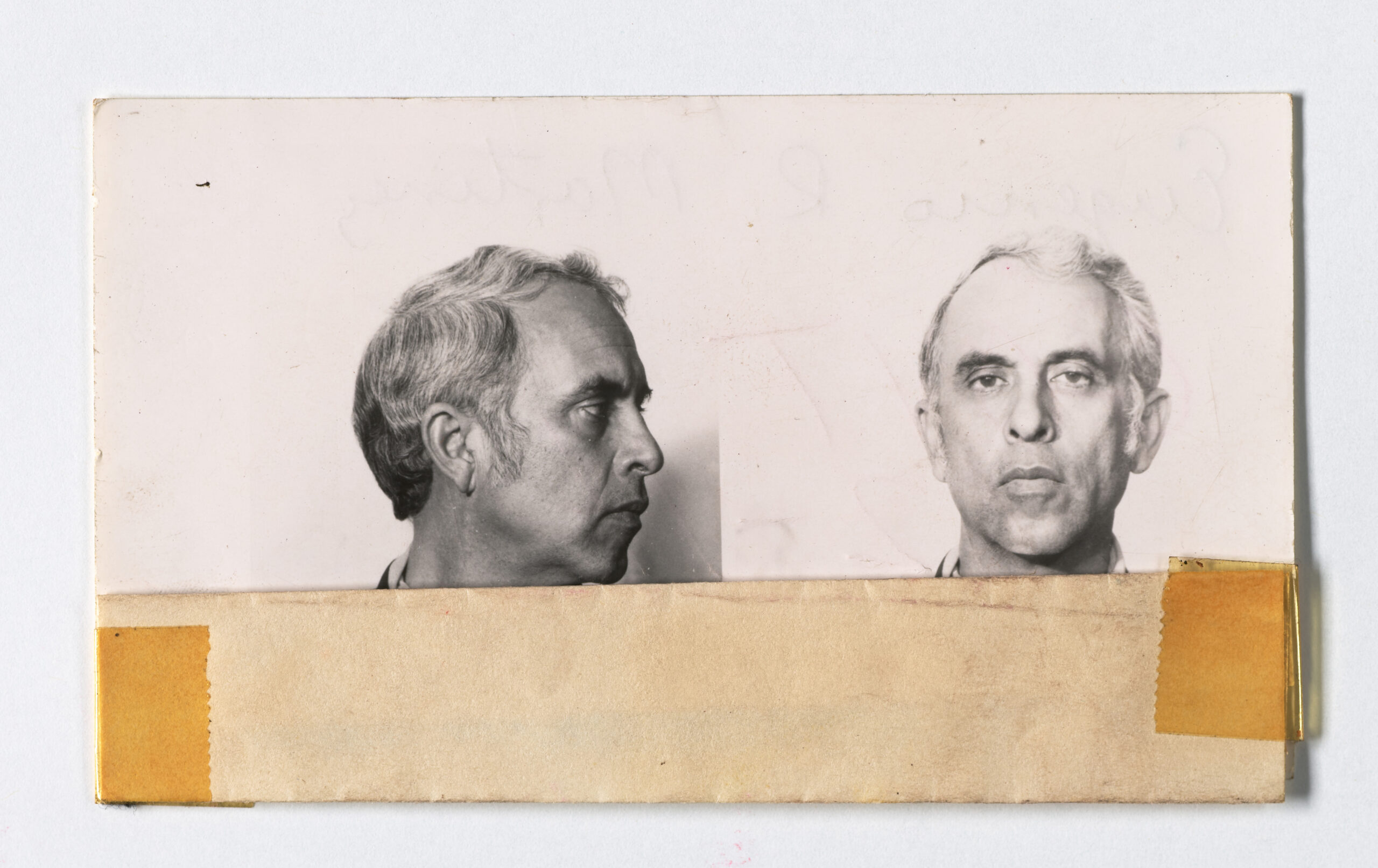

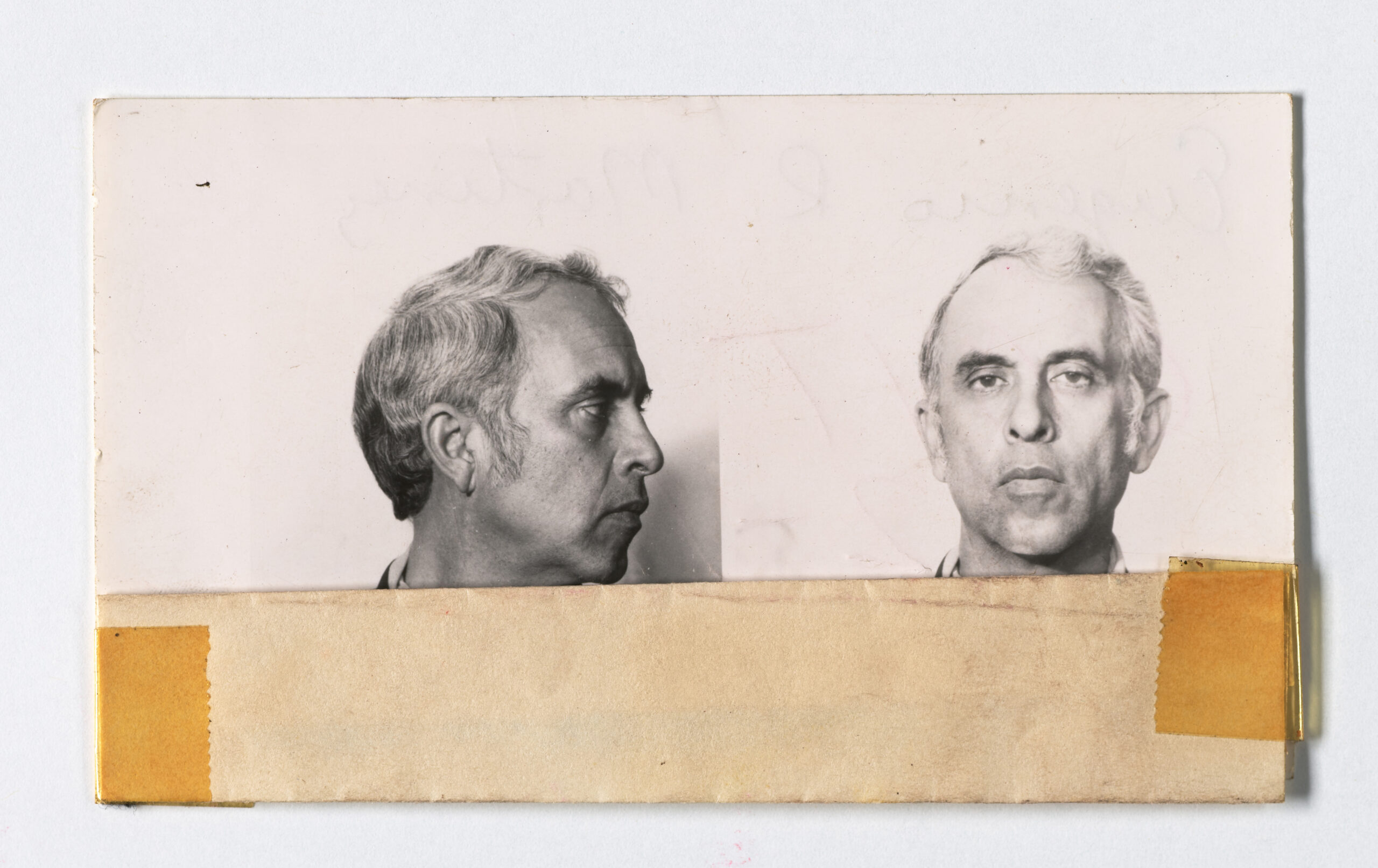

The National Archives Research Services Office has recently digitized all the paper records, exhibits, and artifacts from the trial of United States v. G. Gordon Liddy and has created a portal via which they can be accessed. These records were released in observation of the fiftieth anniversary of the break-in at the Watergate office building. The members of CREEP who participated in the burglary and whose items have been photographed were G. Gordon Liddy, E. Howard Hunt, Bernard Barker, Virgilio Gonzalez, Eugenio Martinez, James McCord, and Frank Sturgis.

View all government exhibits here

Besides the paper records, the items featured on the website include mugshots of the individuals who were arrested, the famous Chap Stick microphones, and photographs that were entered into evidence during the trial. There is also a first-person account in the form of a security log entry by the officer on duty at the Watergate building that fateful night.

To view the text of a document or the full image, click on the image displayed above

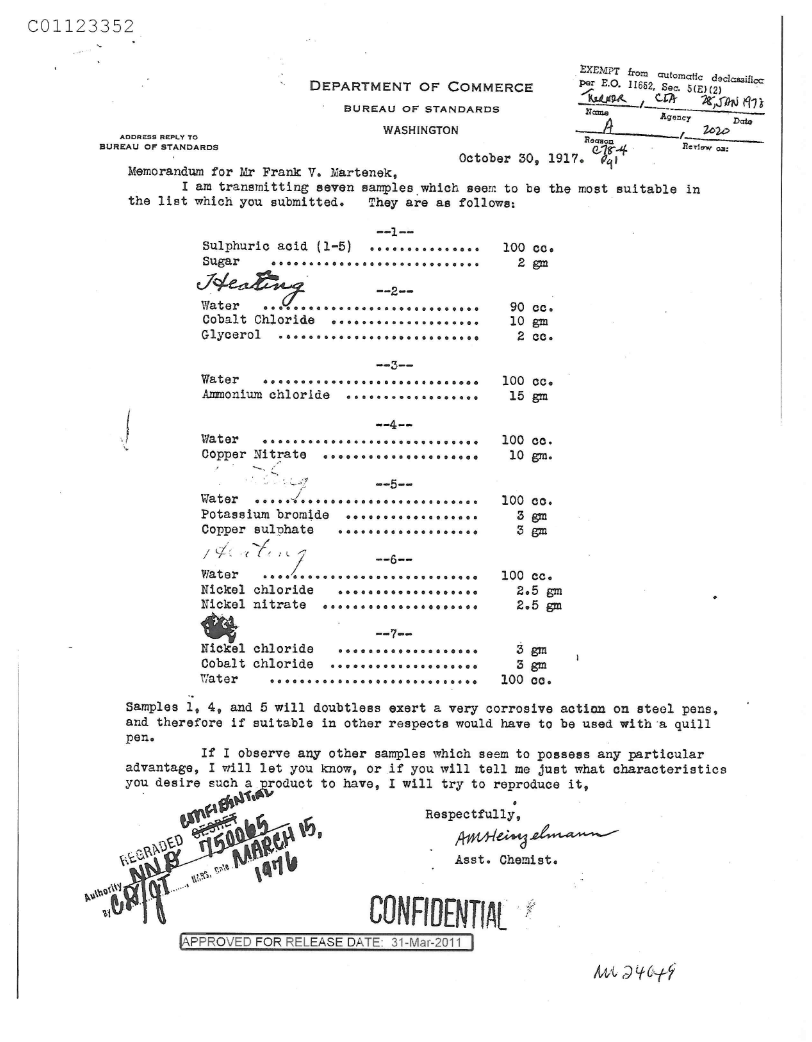

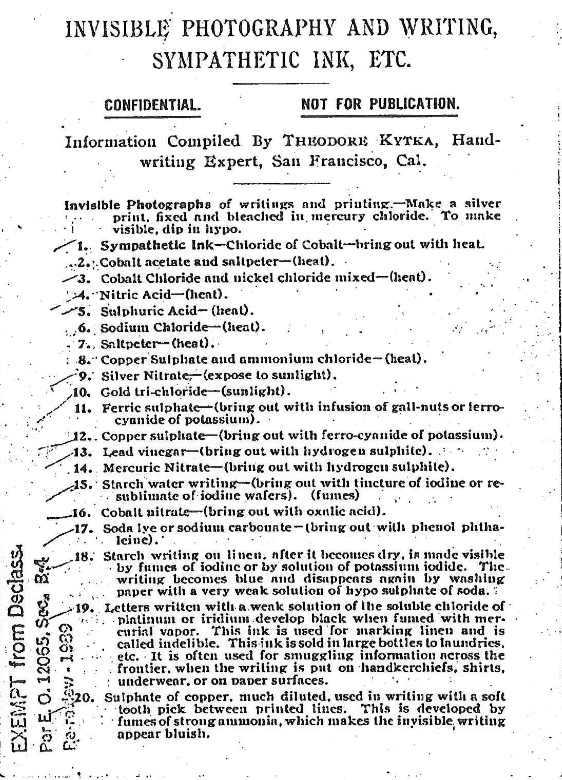

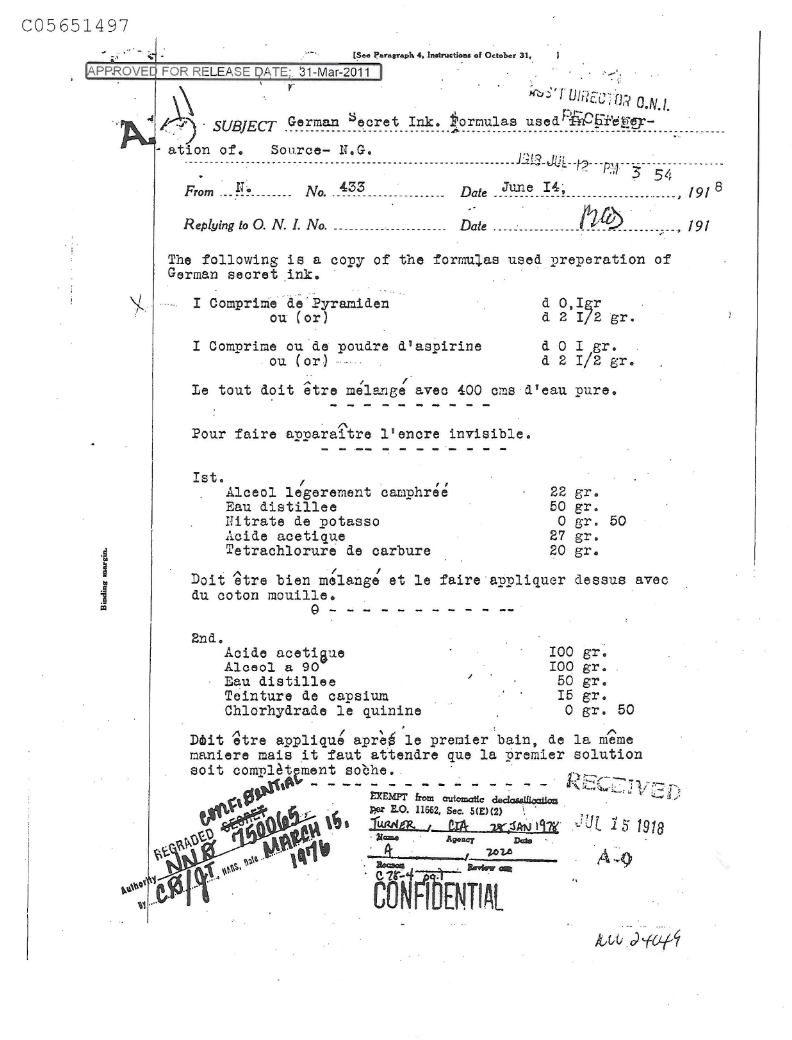

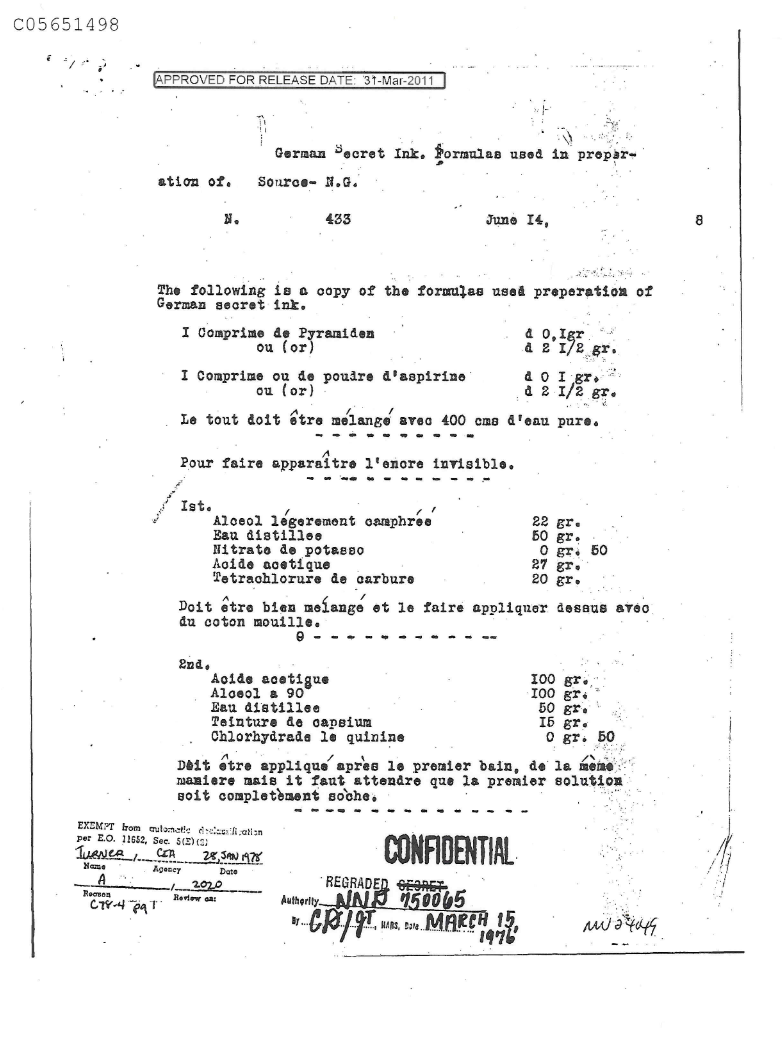

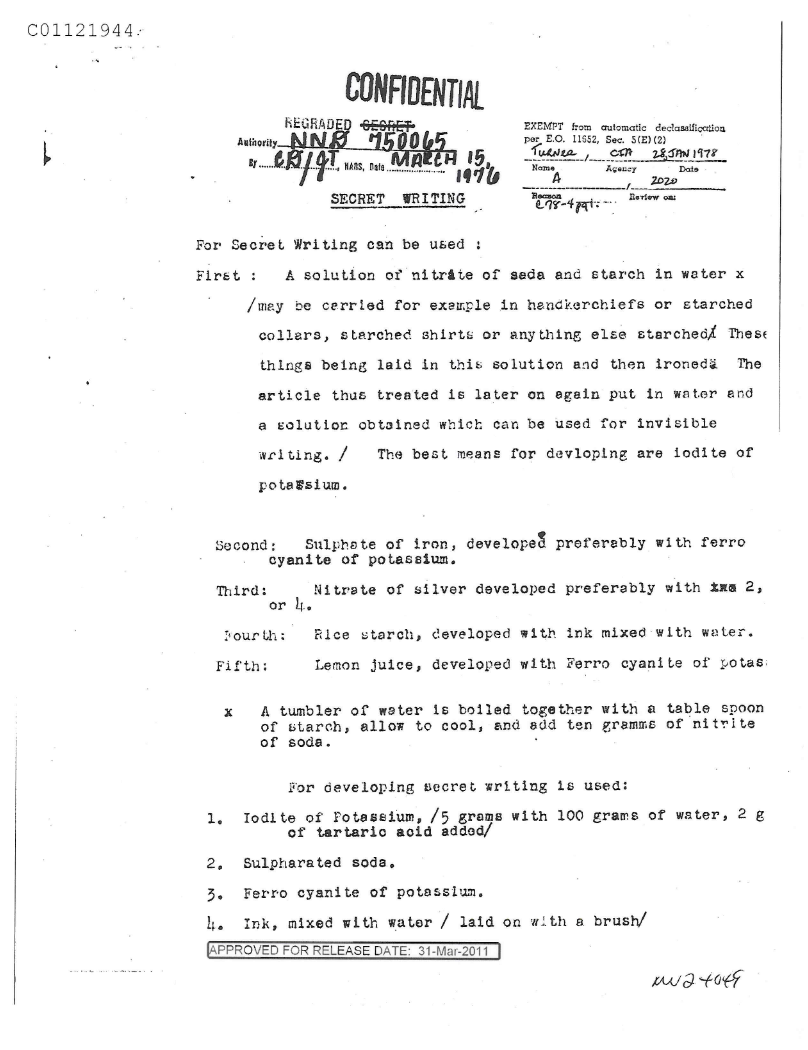

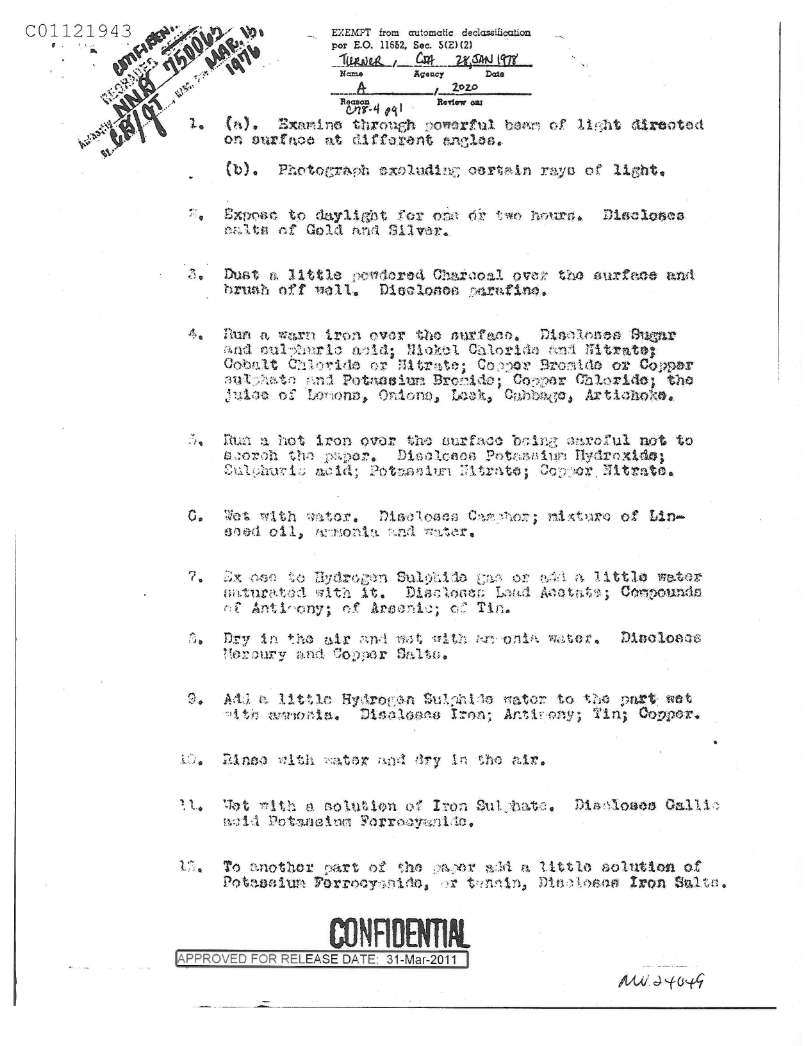

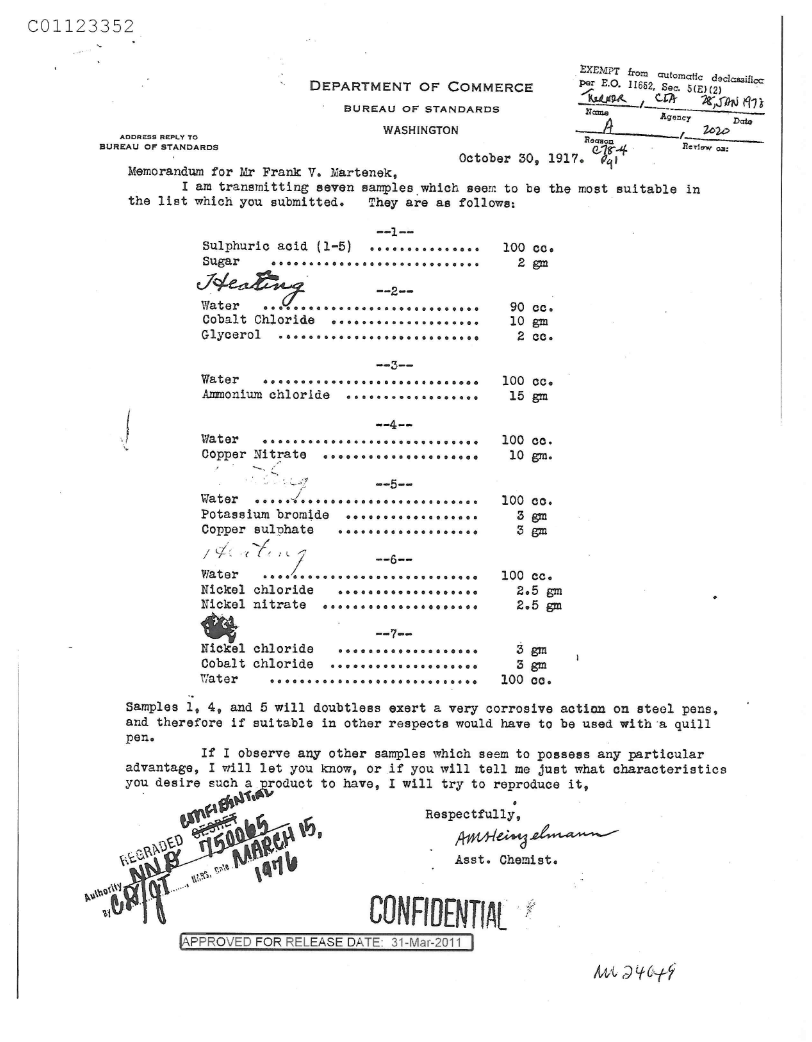

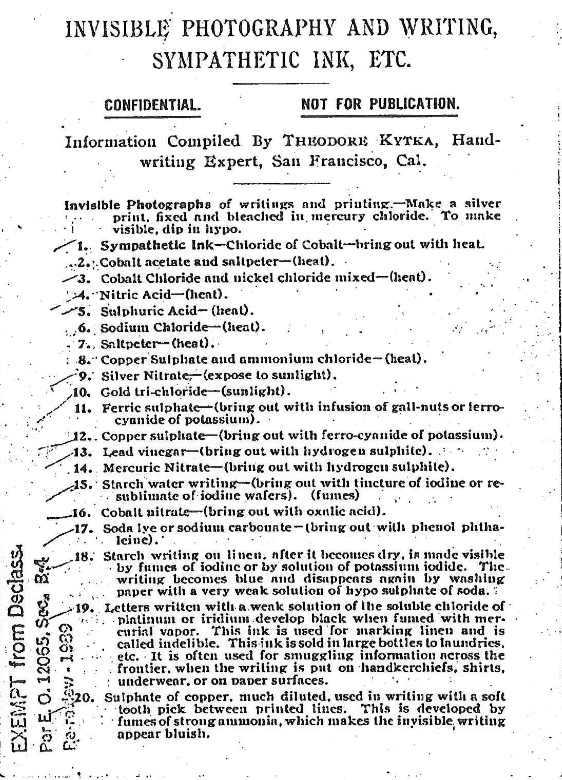

Stealth Communication

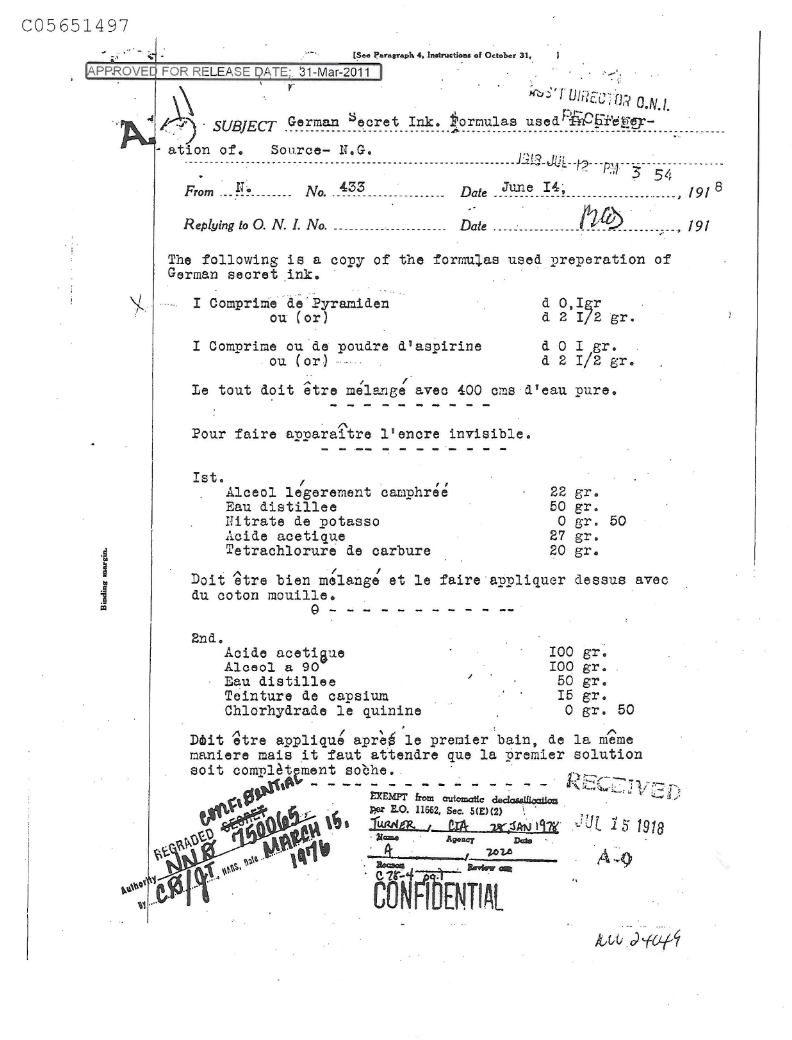

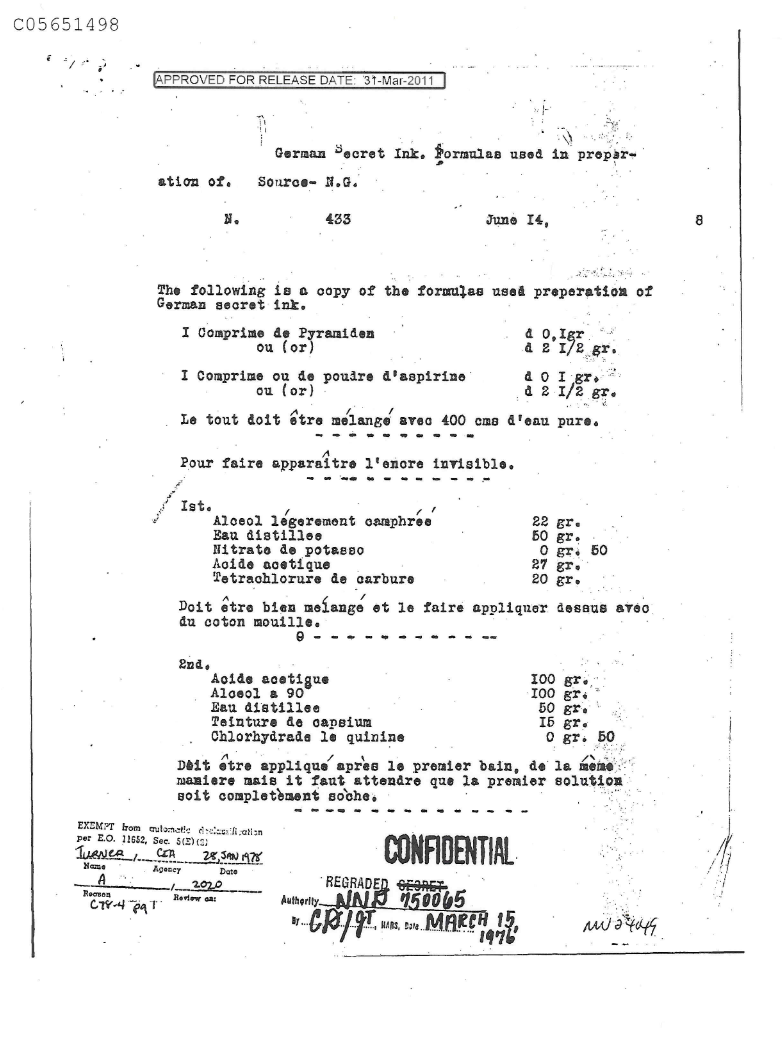

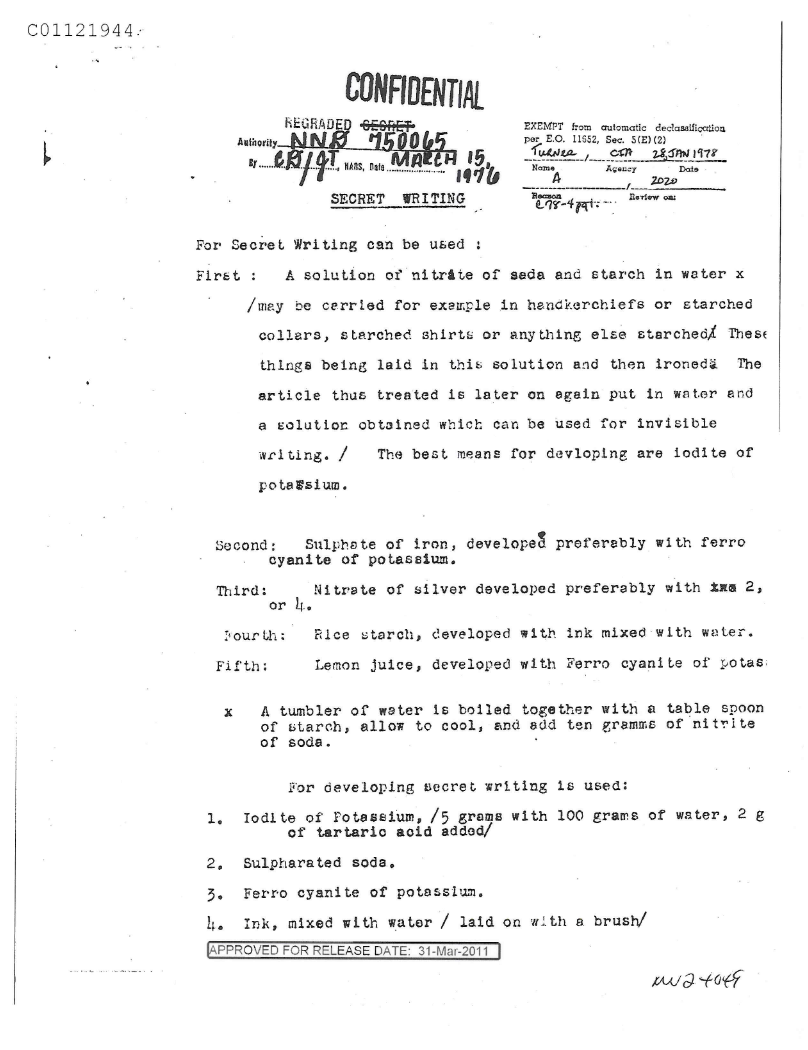

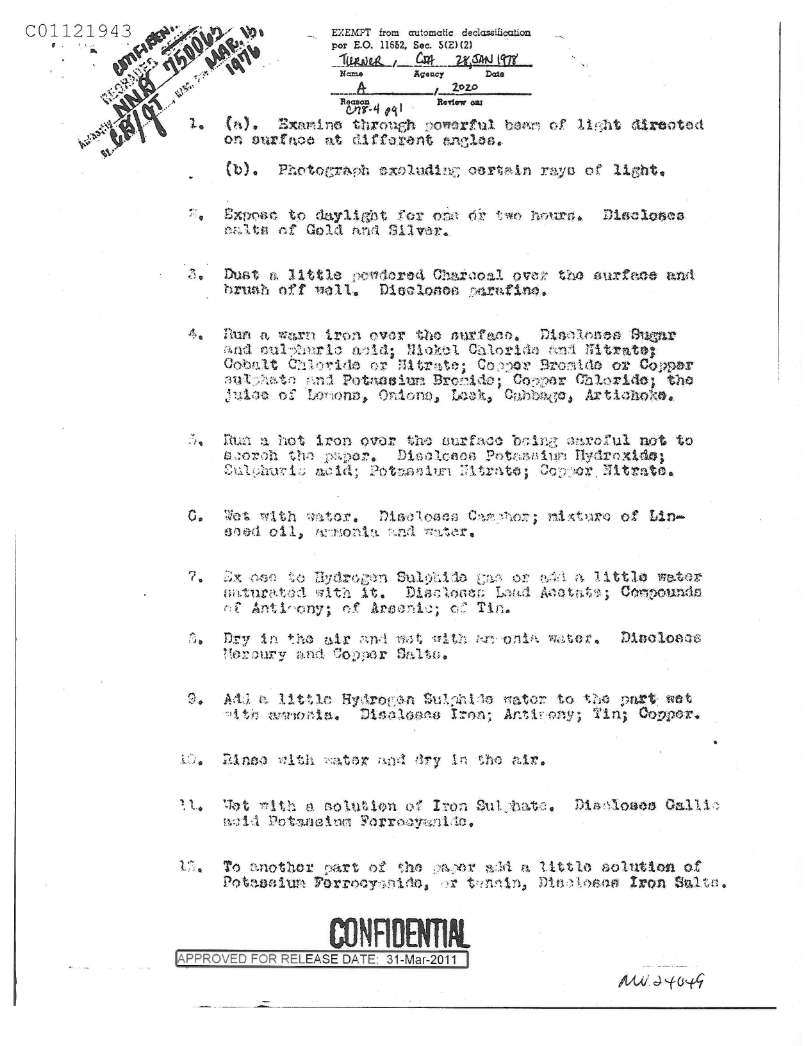

National Archives Displays Newly Declassified Secret Ink Documents from 1918 in July

Source: NARA Press Release from July 11, 2011

When spies pass written messages to other spies or perhaps to their handlers, they might write them with invisible inks. The oldest documents ever released by the National Declassification Center include secret ink formulas developed by the Germans during World War I. Written in French with English translations, the documents include both formulas for the inks and for the methods to make the writing appear. The documents were released on April 19, 2011, in coordination with the Central Intelligence Agency and were displayed from July 11–31, 2011, at the National Archives.

To view the full text of a document, click on the document when it’s the main image above

Civics Corner: What is FOIA?

Requester Best Practices – Filing a FOIA Request

Source: NARA Office of Government Information Services (OGIS)

Signed into law by President Lyndon Johnson (some say he signed it reluctantly) on July 4, 1966, the Freedom of Information Act allows individuals to ask for access to documents generated by federal agencies. Who uses FOIA, and what kind of documents might they ask for? Almost 40 percent of FOIA requests come from businesses, while a large percentage comes from law firms and journalists. Accessing certain documents may help you with research or community involvement – maybe you want to find out if the EPA is recording hazardous materials around your community, or you want your records from traveling in and out of the country from the Department of Homeland Security.

Who Uses FOIA and Why?

Source: Max Galka – FOIAMapper.com

There are nine exemptions that limit individuals’ rights to access such documents, among them documents pertaining to national security and to the internal personnel rules of an agency. If a person’ request for documents is denied, there is a process for appealing the denial.