American Classics

History and art often go hand in hand in a cycle in which one fuels the other. Great and terrible events in American history have inspired iconic works, while an outpouring of art often depicts significant eras in our history, like Civil War photography or the jazz of the Harlem Renaissance.

If primary sources give us the facts, it’s literature that provides us the personal and emotional window into our most consequential eras. When we talk about the Great American Novel, it often refers to the Roaring 20s, the Great Depression, or the unrest of the 60s. That’s because those novels capture those moments in our national identity.

If you’re behind on your reading, this newsletter won’t give you the Sparknotes version of any books. Instead, we’re doing an Archives deep-dive into those individuals who held the pens: our Great American Writers.

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

Beale Street Talks

The Black writer James Baldwin was an early spokesman of the Black experience in America in the middle of the 20th century. Baldwin was born in Harlem on August 2, 1924, to Emma Jones, a single mother. When James was three, Jones married David Baldwin, a Baptist minister.

As a young man, Baldwin was active in his stepfather’s church, serving as a youth minister from the ages of 14 to 16. At DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx, he excelled at writing, working on the school magazine and publishing stories, poems and plays in it. He graduated from high school in 1942 and immediately set about taking any job he could find to help his parents support the seven younger children in the family. He also experienced racial discrimination in public facilities that fueled his anger at the way Black people were treated in the United States.

In July 1943, Baldwin’s father died, and he moved to Greenwich Village, where he befriended the writer Richard Wright, worked any job he could find and started writing a novel. In 1945, Wright helped Baldwin get a fellowship that helped support his writing, and he started to get submissions published in major periodicals like The Nation.

In 1948, at the age of 24, James Baldwin upended his life completely and moved to Paris. It was there that he finally gained the clarity and distance that finally gave him the courage to address the historical and personal issues that became the themes he never abandoned for the rest of his life. “Once I found myself on the other side of the ocean, I see where I came from very clearly…I am the grandson of a slave, and I am a writer. I must deal with both,” Baldwin told “The New York Times.”

In 1953, Baldwin published “Go Tell It on the Mountain,” a semi-autobiographical novel about a Black teenager living in Harlem with his family, especially his fanatically religious stepfather. The book reflected many of the issues of Baldwin’s childhood, specifically the role of the Pentecostal Church, for good and evil, in the Black community. The book was Baldwin’s effort to deal with his issues with his father, and in many ways, it was the book that broke down the barriers that stood between him and his full expression as an artist.

Baldwin spent the next nine years living principally in Paris, although he also traveled to Switzerland, Spain and the United States during that time. He received a Guggenheim fellowship in 1954, the year before he published “Giovanni’s Room,” a novel about an American living in Paris, his American fiancé and his male Italian lover. All the characters in the novel are white, and it was Baldwin’s first public exploration of homosexuality and bisexuality. Despite his publisher’s fears that the book would ruin Baldwin’s reputation, “Giovanni’s Room” was well received by critics. The BBC News ranked it as one of the 100 most influential novels on November 5, 2019.

Baldwin also published a series of collections of essays that established him as a chronicler of the Black experience. Through “Notes of a Native Son” (1955), “Nobody Knows My Name: More Notes of a Native Son” (1961) and “The Fire Next Time” (1963), he became one of the best-known voices in the early Civil Rights Movement, describing the realities of race relations in America that white Americans could not turn away from. “If one wishes to know how justice is administered, one does not question the policemen, the judges, or the protected members of the middle class. One goes to the unprotected—those, precisely, who need the law’s protection most!—and listens to their testimony,” he wrote in “No Name in the Streets” (1972).

As time passed and things did not improve for Black Americans, and as Black leaders like Medgar Evers, Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X fell to assassins’ bullets, James Baldwin became more discouraged, but he was never entirely disheartened. He continued to write essays, novels, plays and poems and to speak out on matters of racial equity. He taught at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and at Hampshire College, and he continued to live in both the United States and France, where he died in 1987.

To view the text of a document or the full image, click on the image displayed above

Slapstick Novels

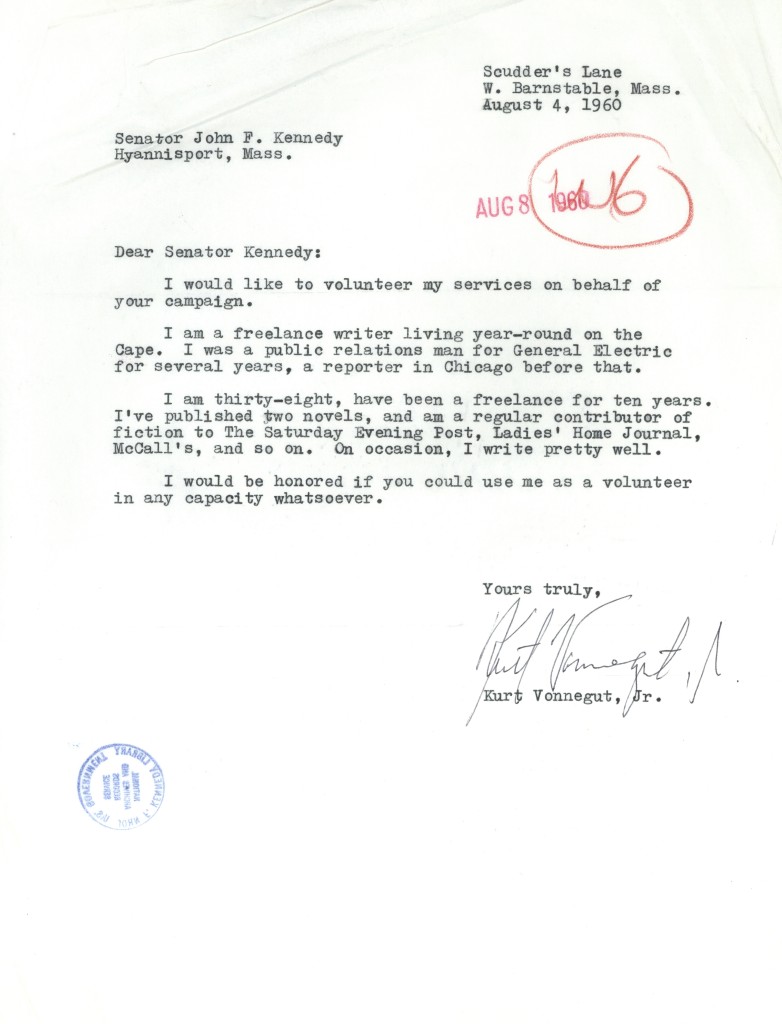

Kurt Vonnegut letter to JFK

Source: JFK Library’s An Inside Look blog

At first glance, Kurt Vonnegut’s upbringing would appear to have been quite conventional. He was born on November 11, 1922, in Indianapolis, Indiana, and raised there along with his older brother Bernard and his sister Alice by his architect father Kurt Vonnegut, Sr., and his mother Edith Lieber. The Vonneguts were long-established members of the Indianapolis community, his great-grandfather having started a hardware company there in the 19th century. The Great Depression disseminated Kurt Vonnegut, Sr.’s architectural practice, forcing him to sell the family home and send his younger son to attend public high school instead of the private schools his brother and sister had gone to. Vonnegut, Sr., reacted to his loss of fortune by succumbing to a near-permanent state of despair, while his wife, who came from a very wealthy family, never recovered from loss of her social standing in the community. She became addicted to alcohol and prescription drugs.

Although he was a member of the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC), Vonnegut lost that position because his grades at Cornell were bad and his pacifist attitudes were not appreciated in the run-up to World War II. He dropped out of school and enlisted in the Army in 1943. He was trained to fire howitzers and then in mechanical engineering in a special program, but the Army needed infantrymen to support the D-Day invasion in Europe, so the program was canceled, and Vonnegut was sent to Camp Atterbury, south of Indianapolis. When he went home for the Mother’s Day weekend in 1944, he learned that his mother had committed suicide.

Three months later, he was shipped out to Europe with the 106th Infantry Division. In the Battle of the Bulge, more than 6,000 members of the division, including Vonnegut, were captured on December 22, 1944. They were sent to Dresden, Germany, by boxcar, where they were housed in a slaughterhouse and forced to work in a factory making malt syrup for pregnant women.

Then, starting on February 13, 1945, the Allies bombed Dresden over a period of two days, dropping first explosives and then waves of incendiary bombs. More than 1,600 acres in the center of the city burned; estimates of casualties vary from 25,000 to more than 60,000. To this day, whether the firebombing of Dresden was necessary is subject to debate. Some have argued that the city had virtually no strategic value to the Nazis and the war was nearly over, while others have contended that Dresden was one of the last industrial and communications hubs still functioning in Germany.

Vonnegut and other POWs survived the Allied attacks by hiding in a meat locker several stories below street level. When they emerged, they were put to work excavating the dead from the rubble. The experience marked Vonnegut for life, but it was years before he had processed the events sufficiently to turn them to artistic gold.

Once he returned, Vonnegut sold short stories and essays to national magazines. Emboldened by this success, he quit the job at GE and moved his family to Cape Cod, where he embarked on the life of a freelance writer. He published his first novel, “Player Piano,” in 1952. Vonnegut received an offer to teach at the Iowa Writer’s Workshop, which in turn led to his being awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship. He used those funds to return to Germany in 1967 to do research, specifically to research the firebombing of Dresden. He was stunned to see on his return that the city still was largely in ruins. Although he had been trying to write about his experiences there for years, it was his return to the scene of the disaster that finally gave him the energy to shape them into his greatest work, “Slaughterhouse-Five or, The Children’s Crusade: A Duty-Dance with Death.”

The protagonist of the novel, Billy Pilgrim, is a time traveler who survives the firebombing of Dresden, dies, is miraculously alive again in the next chapter, is kidnapped to another planet, and suffers flashbacks and what most certainly is PTSD, even though that disorder had not been identified when the book was written. These events, by the way, are not described in chronological order. Published in 1969, the book was Vonnegut’s first bestseller, staying on the New York Times list for 16 weeks. It is an unabashed anti-war novel, rife with black humor and riddled with death. The timing was especially apt, since the Vietnam War was ramping up at precisely that moment. The novel firmly established Vonnegut as an American author to be reckoned with.

He published the novels “Breakfast of Champions” (1973), “Slapstick” (1976), “Jailbird” (1979), “Deadeye Dick” (1982), “Galápagos” (1985), “Bluebeard” (1987), “Hocus Pocus” (1990) and “Timequake” (1997) and the short fiction collections “Canary in a Cat House” (1961), “Welcome to the Monkey House” (1968), “Bagombo Snuff Box” (1997), “God Bless You, Dr. Kevorkian” (1999), and “Armageddon in Retrospect” (2008). The last was organized by his son Mark and published posthumously.

More context:

Records of the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey (Record Group 243)

National Archives Record Group Explorer

Kurt Vonnegut died on April 11, 2007, of injuries sustained from a fall at his brownstone home in New York City. He was 84 years old. He had written 14 novels, five nonfiction books, three short-story collections and five plays when he passed.

Throughout his work, the themes of war as an inevitable and bloody business, wealth and its inequitable distribution, the evils of capitalism, the loss of free will, estrangement from family and lack of purpose in life ring true. “[H]e writes about the most excruciatingly painful things,” Michael Crichton wrote in The New Republic. “His novels have attacked our deepest fears of automation and the bomb, our deepest political guilts, our fiercest hatreds and loves. No one else writes books on these subjects; they are inaccessible to normal novelists.”

A Beloved Author

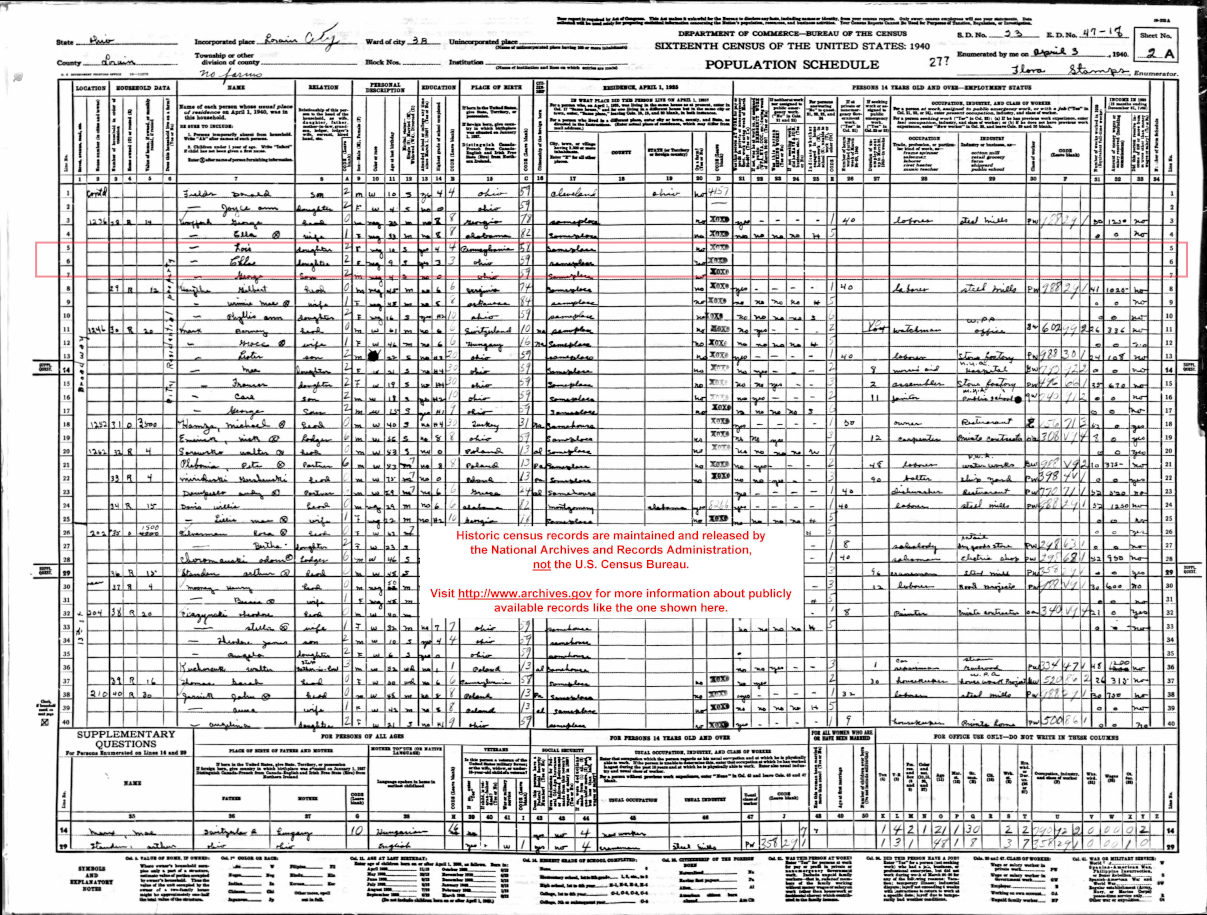

Toni Morrison in the 1940 Census

Source: United States Census Bureau

Born Chloe Ardelia Wofford on February 18, 1931, in Lorain, Ohio, Toni Morrison adopted her nickname from her baptismal name, “Anthony,” which she took from St. Anthony of Padua when she joined the Catholic Church at the age of 12. When she entered Howard University in Washington, D.C., in 1949, she began calling herself “Toni” when her classmates were baffled by “Chloe.”

She had grown up in an integrated, working-class neighborhood, the daughter of Ramah Willis, a homemaker, and George Wofford, a welder who worked for U.S. Steel. She graduated from Howard with a bachelor’s degree in English and went on to Cornell, where she completed a master’s degree in 1955. She taught at Texas Southern University in Houston for two years and then at Howard for seven more, where she met and married Harold Morrison, an architect from Jamaica, in 1958. The couple had two sons, Ford and Slade. They divorced in 1964, and Morrison went to work as a textbook editor for L. W. Singer, a division of Random House. In 1967, she transferred to Random House in New York as the first black woman senior editor of the fiction division.

During this period, while she was working a day job and caring for her two sons, Morrison completed her first novel, “The Bluest Eye,” published in 1970. Set in 1941 in Morrison’s hometown of Lorain, Ohio, the book tells the story of Pecola, an African American woman who longs to have blue eyes because she equates them with whiteness and she believes she is ugly because of her dark skin. The book’s themes of child molestation, incest and racism immediately made it controversial, but they also set Morrison on a path of truth-telling from which she did not waver throughout her life as a novelist.

She went on to publish 10 more novels, all of them explorations of Black identity in America and many of them examinations of the experiences of Black women. She did not flinch from discussing how the past impinges on the present—most specifically, on how the legacy of slavery impinges on the lives of the Black characters in her books, regardless of the era in which her novels are set. Her best-known work, “Beloved,” is about a former slave, Sethe, who escapes her enslavers’ plantation in Kentucky to Cincinnati in about 1856, only to be tracked down and threatened with being returned to the plantation. Sethe then murders her infant daughter rather than see her returned to slavery. Nearly 20 years later, Sethe and her household are haunted by her murdered daughter’s ghost made manifest.

Toni Morrison receives the Presidential Medal of Freedom

National Archives

In all her fiction, Morrison recounted her stories with unforgettable style. “Ms. Morrison animated that [American] reality in prose that rings with the cadences of black oral tradition,” The New York Times said in her obituary. “Her plots are dreamlike and nonlinear, spooling backward and forward in time as though characters bring the entire weight of history to bear on their every act.”

Morrison won the American Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize for “Beloved” in 1988, and the National Book Critics Circle Award in 1977 for “Song of Solomon.” In 1993, she became the first African American woman to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. She won the National Book Foundation’s Medal of Distinguished Contribution to American Letters in 1996 and the National Humanities Medal in 2000. In 2012, she received the President Medal of Freedom from President Barack Obama.

For many years, Morrison was on the faculty at Princeton University, where she lectured regularly and where her papers are preserved. She also co-wrote a number of books with her younger son, Slade. Morrison died at the age of 88 in the Bronx, New York City, on August 5, 2019.

A Planted Life

Emily Dickinson, who wrote much, published almost nothing in her lifetime and died a virtual invalid at the age of 55, is now one of the most best-known American poets. Her work is taught in English classes from middle school through college—it is frequently the first poetic work any American student reads in school.

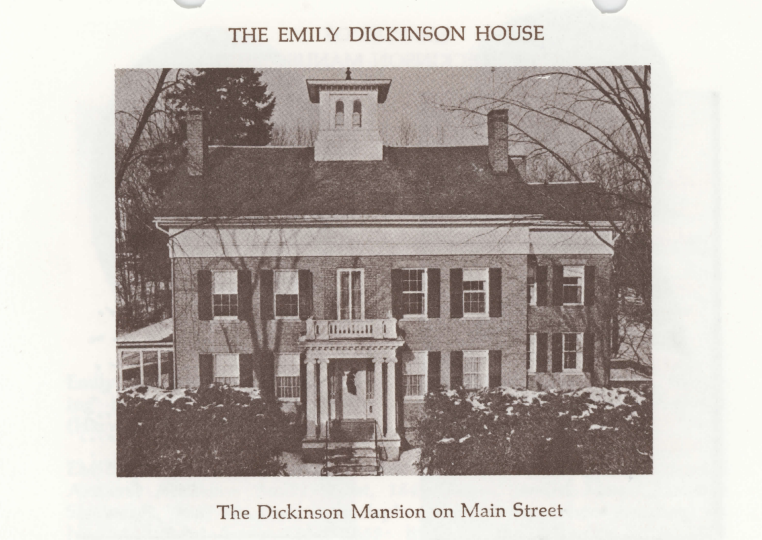

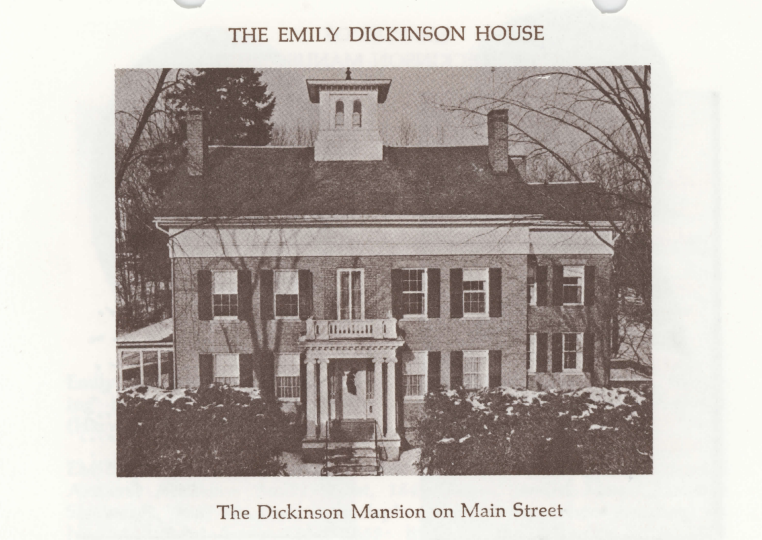

Emily Elizabeth Dickinson was born in Amherst, Massachusetts, on December 10, 1830, into a prominent family. Her father was Edward Dickinson, a lawyer and a trustee of Amherst College, and her mother was Emily Norcross. Their three children were William Austin, called by his middle name; Emily Elizabeth; and Lavinia Norcross. The Dickinsons were an intellectual family, reading widely and discussing what they read. Austin also became an attorney. He married Susan Gilbert, and his father built the couple a house next door to the family home. Susan Gilbert and Emily Dickinson became very close friends.

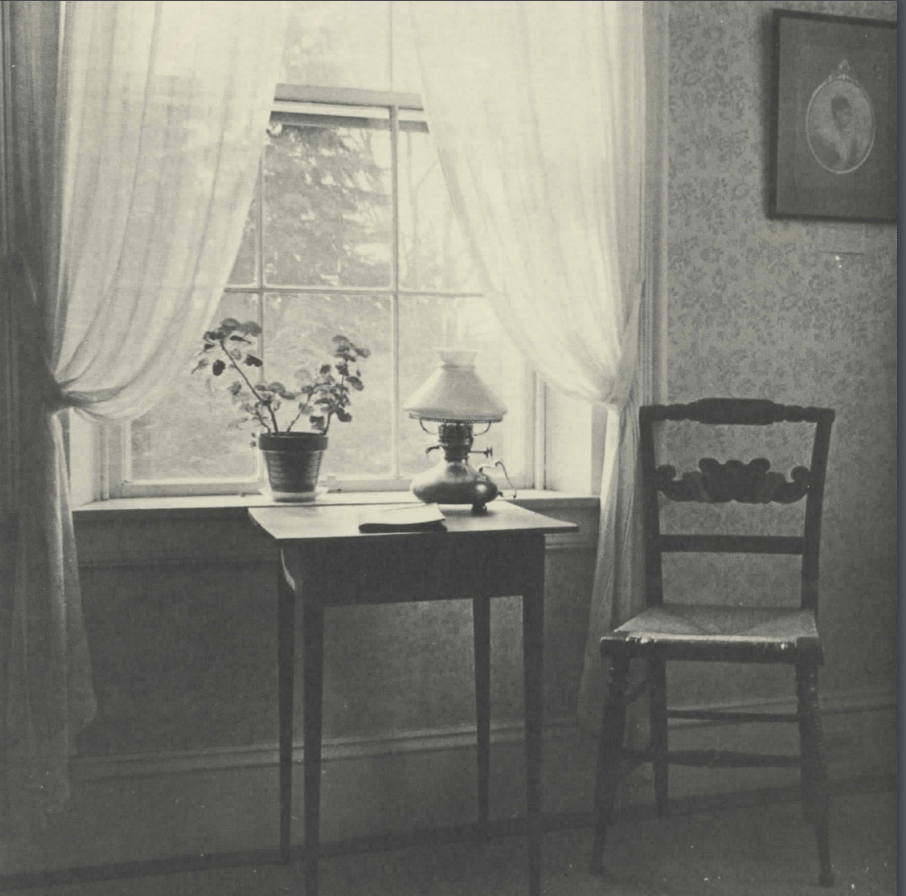

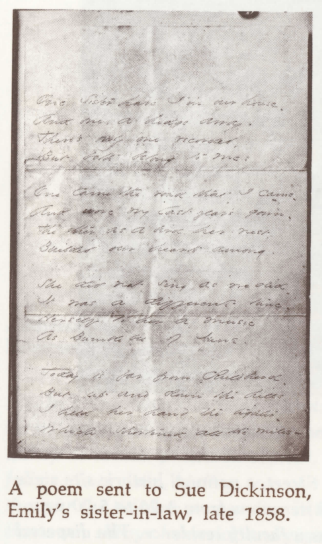

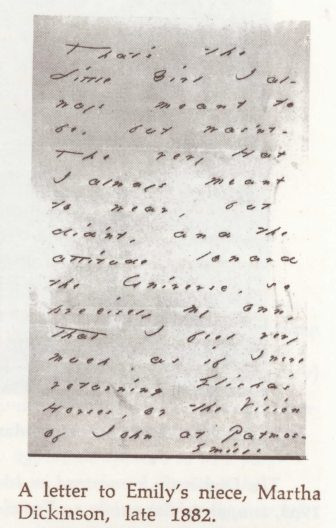

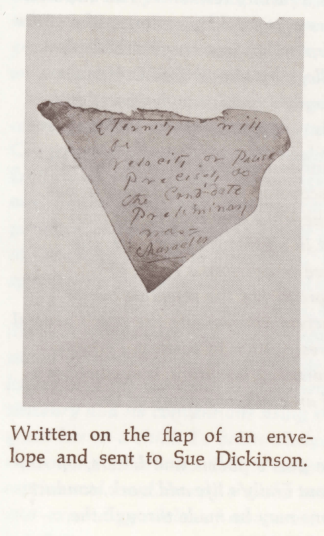

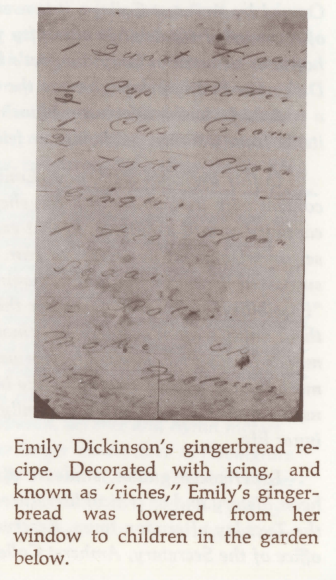

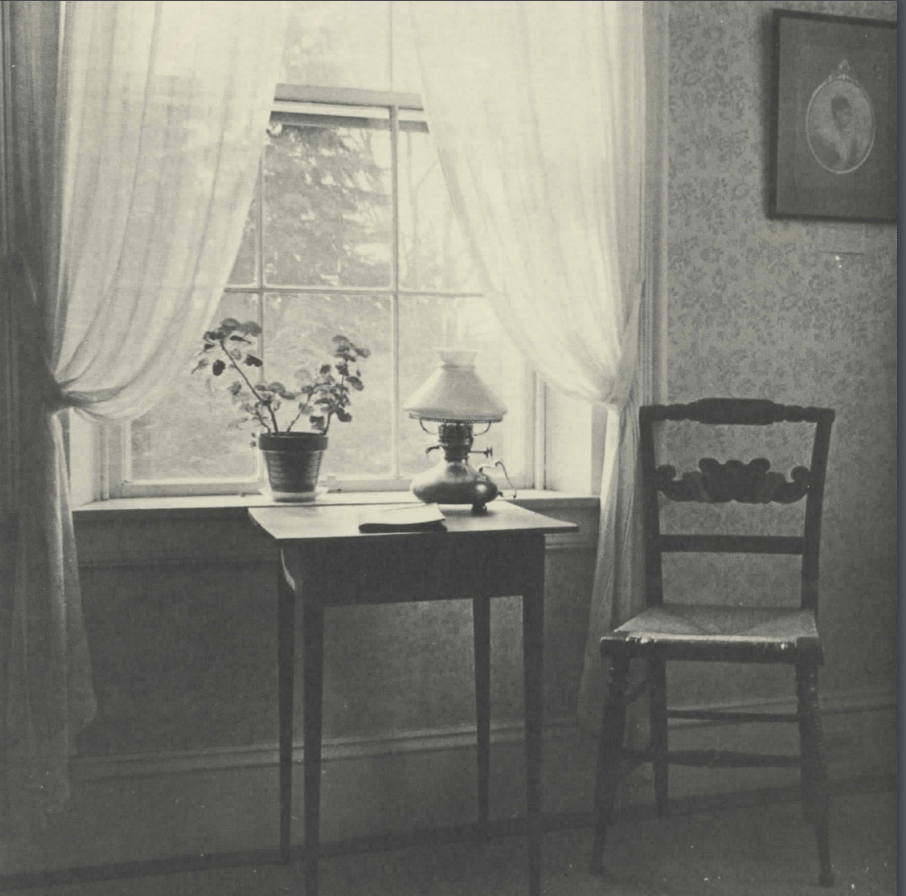

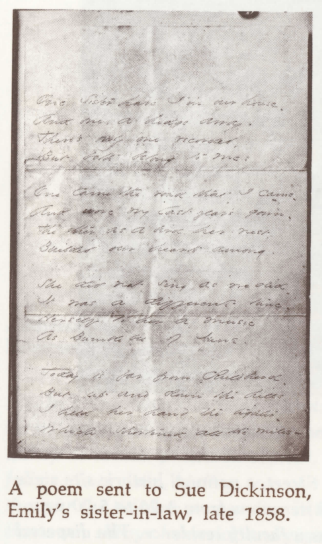

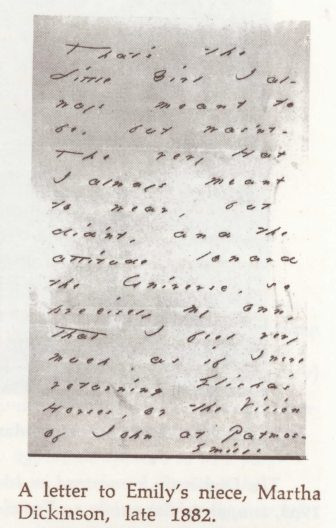

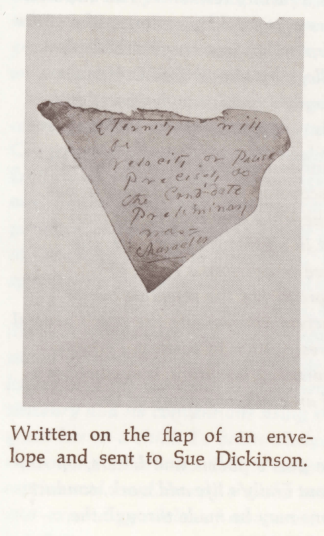

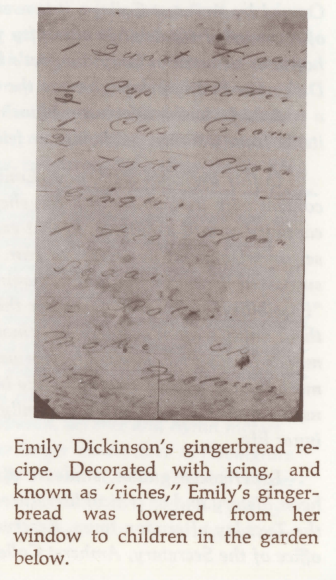

Except for one year, 1847-1848, when she studied at Mount Holyoke Female Seminary in South Hadley, Massachusetts, Emily Dickinson lived exclusively at home with her family. Neither she nor her sister Lavinia ever married. Throughout her life, Dickinson wrote poems and sent them to her close friends, but during her lifetime, only a handful (some sources say seven, some say 10) were published. Dickinson spent her time taking care of her household and tending her garden, which was often a subject in her poetry. She became increasingly reclusive as she aged, sometimes not leaving her bedroom for days on end.

Upon Emily Dickinson’s death at the age of 55 in 1886, her sister Lavinia discovered 40 notebooks containing 1,800 poems, punctuated with unusual dashes that did not coincide with the conventions of the day. Lavinia then took it upon herself to see Emily’s work published. The first volume of her works was published four years after her death, but it was not until 1955 that her original versions, complete with her annotations, were published in Complete Poems.

An unrelated fun fact: Dickinson wrote almost all of her poems in a meter that can be sung to the tune of a familiar song: The Yellow Rose of Texas.

To view the text of a document or the full image, click on the image displayed above

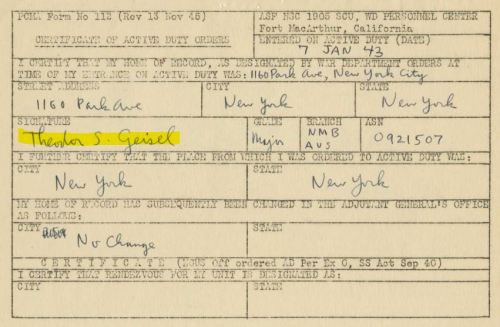

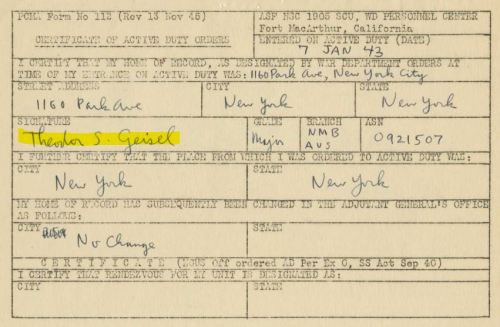

Won’t You Try Green Eggs and Ham?

“Dr. Seuss” was the pseudonym of Theodor Seuss Geisel, the author of more than 60 books for children. Born in 1904 in Springfield, Massachusetts, Geisel graduated from Dartmouth College in 1925. He chose his pen name while still an undergraduate. He then attended Lincoln College, Oxford, in the UK, where he planned to complete a Ph.D. in English literature and become a professor, but he met Helen Palmer, who persuaded him that he should pursue a career as an artist instead. Palmer had seen Geisel’s notebooks and was impressed by the drawings of animals that filled the pages.

Geisel returned home to Springfield, where he began sending his writing and drawings to publishers, advertising agencies and magazines. By late 1927, he had landed a job at Judge magazine as a writer and illustrator, and he and Palmer were married that November.

Geisel quickly branched out into magazine submissions and advertising work, which paid him handsomely for his work. He and Palmer had no children. They traveled extensively, and it was on a trip back from Europe in 1936 that Geisel was inspired by the rhythm of the ocean liner’s engines to write his first children’s book, “And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street,” an allusion to the street he grew up on in Springfield. Geisel stated that between 20 and 40 publishers rejected the manuscript before he happened to run into an old Dartmouth classmate, which resulted in the book’s publication by Vanguard Press in 1937.

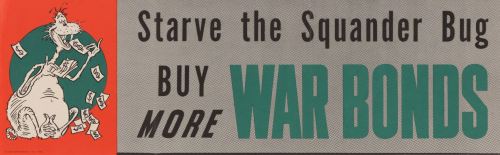

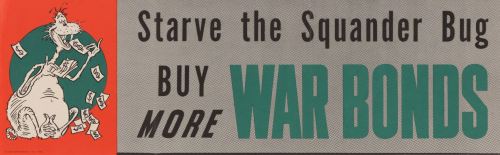

At the height of World War II, Geisel served in the military, and his talents were aptly used. He wrote and illustrated inspirational cartoons, posters, movies, and news stories to both recruit new soldiers and motivate existing ones. Geisel’s work in the Military Motion Picture Unit resulted in the creation of “Private Snafu,” a character that appeared in 27 military-produced films to teach soldiers basic safety and military protocol.

And the rest, as they say, is history. Dr. Seuss had sold more than 600 million copies of his books, which had been translated into more than 20 languages by the time he died in 1991. Publishers Weekly compiled a list of the best-selling children’s books of all time in 2000. Geisel had written 16 of the top 100 hardcover books on the list: “Green Eggs and Ham” (number four), “The Cat in the Hat” (number nine) and “One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish” (number 13). His last children’s book “Oh the Places You’ll Go” is a popular gift for graduates.

To view the text of a document or the full image, click on the image displayed above

Dr. Seuss “Private Snafu” – used to recruit and inspire soldiers during WWII

(4 minutes 43 seconds)

Source: NARA YouTube channel