America On Stage

Is there a place more evocative of America than Broadway? People come from all over the country to try to make it onto the stage in the Big Apple, and seeing a show in one of New York’s iconic theaters is at the top of the list for many visitors.

Composers and directors take their inspiration from many different sources, and history is one of them. Dozens of historical events have been adapted for the stage. But instead of breaking into song, we’re using the National Archives records to tell the story.

Places everyone! The show is about to begin!…

In this issue

History Snack

Overture: Oklahoma!

Letter from Teddy Roosevelt re: Oklahoma statehood

National Archives Identifier: 7268651

Set in Indian Territory in 1906, outside the town of Claremore, Oklahoma! was the first musical produced by composer Richard Rodgers and lyricist-dramatist Oscar Hammerstein II, who went on to create eight more Broadway productions. Oklahoma! opened on Broadway on March 31, 1943 and ran for 2,212 performances. It has been staged in London’s West End and revived several times both on Broadway and the West End, sent on tour around the country and around the world, and adapted as an Oscar-winning film of the same name.

The events of Oklahoma! takes place in the years after the Land Run of 1889, when President Benjamin Harrison, on authorization from Congress, proclaimed that two million acres were open for settlement. Each person could claim up to 160 acres of public land, and after living on the land for five years, they could receive a title. At noon on April 22, 1889, thousands of hopeful landowners gathered at various points of entry around Indian Territory on their fastest horses or in covered wagons containing all their possessions. At the crack of a gun or boom of a cannon (depending on your point of entry), the race was on.

Although this land was marketed as “up for grabs,” it had originally belonged to five Indigenous tribes: the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole. For the federal government to take possession of these lands, the tribes were relocated by legislation such as the Dawes Act of 1887, which severely restricted Indigenous reservations.

Dawes Act of 1887

National Archives Identifier: 5641587

The story of Oklahoma! describes the competing courtships of cowboy Curley McLain and farmhand Jud Fray for the hand of farm girl Laurey Williams, which frames the broader and more bitter story of the rivalry between the cowboys and the farmers in Indian Territory over water rights and fences. In the end, Curley renounces his cowboy profession to marry his Laurey. They are wed just as the Indian Territory is about to become the state of Oklahoma. At the last minute, a drunken Jud appears and challenges Curley to a fight. In the conflict, Jud falls on his own knife and dies. Curley is acquitted in an impromptu trial, and Curley and Laurey ride off to their honeymoon in the surrey with the fringe on top.

Oklahoma! was quite innovative in that it told an engrossing story with interesting characters, songs and dances that were well integrated into the plot, and themes that recurred throughout the musical. Rodgers and Hammerstein were definitely on to something, and they worked this formula to great success for many years to follow.

Act I: I’d Rather Be Right

George M. Cohan as FDR on Broadway

Source: FDR Forward with Roosevelt blog

Opening on Broadway on November 2, 1937, after a preview run in Boston, the musical I’d Rather Be Right took satirical aim at President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and his New Deal policies. Including a sitting President as a main character in a Broadway musical was unheard of at the time, let alone in one that dared to poke fun at the man and his plans for the country.

Cohan’s FDR with the Supreme Court on Broadway

Source: FDR Forward with Roosevelt blog

The show was the brainchild of producer Sam Harris, who teamed up writers Moss Hart and Pulitzer Prize-winner George S. Kaufman with songwriters Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart to create the musical. Despite the formidable track records of all those men, the story they came up with was silly beyond belief—in the middle of the Great Depression, young Peggy Jones and Phil Barker want to get married, but Phil needs a raise first. Who comes to their rescue? None other than FDR himself, who enlists the aid of his cabinet and generously offers to extend his presidency for another 10 years to make sure his economic policies bear fruit. In the end, in a flash, it all turns out to have been a dream (does anybody here remember the ninth season of Dallas?), but the President delivers one last rousing speech about the future of the country, and all is well.

The show was a smash, running for 290 performances.

No doubt the musical would not have fared so well had it not been for its electrifying leading man, George M. Cohan, a legendary American performer whose vaudevillian parents took him on stage when he was a babe in arms and then had him singing and dancing with them as soon as he could walk and talk. They also conveniently lied about his birthday, which was July 3, 1878, insisting he was “born on the Fourth of July.”

Cohan as FDR with full ensemble

Source: FDR Forward with Roosevelt blog

In his lifetime, Cohan published more than 300 songs, including “Give My Regards to Broadway” and “Over There,” the most popular song in America during World War I. He created and produced more than 50 musicals between 1904 and 1920. By 1937, when producer Sam Harris pitched Cohan the idea of I’d Rather Be Right, the song-and-dance man had been in and out of retirement several times over the past several years, and he was not particularly impressed with the new show. But he let himself be persuaded, and he threw himself into his performances with gusto, singing at the top of his lungs, dancing up a storm, exhorting his fellow Americans to keep the faith.

And it seems that most folks got the message the show was sending about the President. “Despite its genial aimlessness, I’d Rather Be Right succeeds in venturing with impunity into an almost unprecedented form of satire,” the reviewer for Time wrote on November 15, 1937. “No stage has ever had such temerity in lampooning members of an existing government by name. Playwrights Kaufman & Hart call no bad names but give all the right ones.”

Perhaps practicing one of the first clear demonstrations of the notion that any publicity is good publicity, Roosevelt kept any opinions he might have had about I’d Rather Be Right to himself. However, in 1940, when he presented George M. Cohan with a gold medal authorized by Congress, he called the actor his “double.” There can be little doubt about what FDR was referring to.

Letter from the National Democratic Council denouncing the FDR Broadway show

Source: FDR Forward with Roosevelt blog

Resolution from the National Democratic Council denouncing the FDR Broadway show

Source: FDR Forward with Roosevelt blog

FDR inviting George M. Cohan for a Congressional Medal

Source: FDR Forward with Roosevelt blog

Request for photos from Cohan’s medal presentation

Source: FDR Forward with Roosevelt blog

Letter to FDR re: Cohan’s medal

Source: FDR Forward with Roosevelt blog

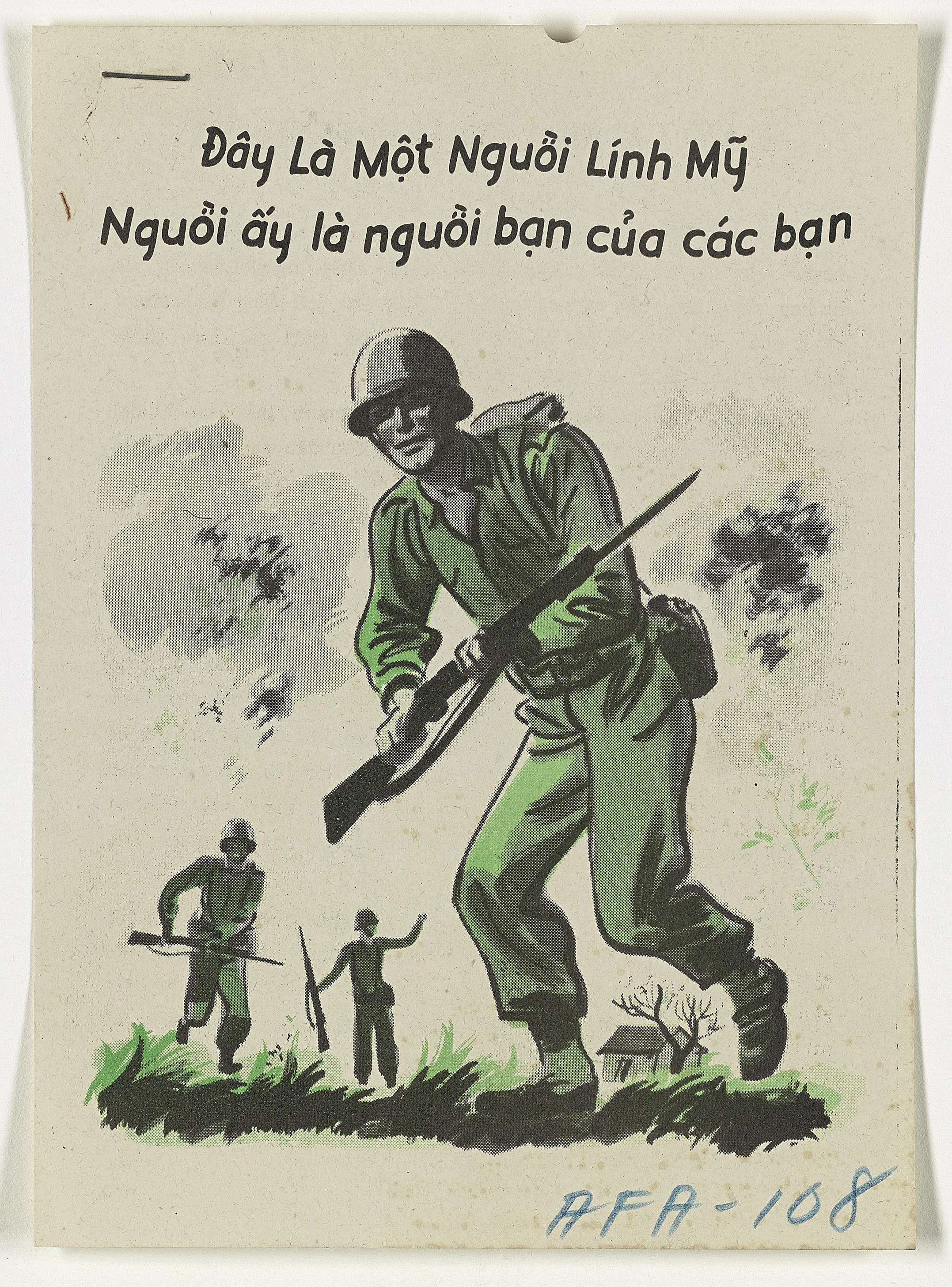

Act II: Miss Saigon

Drawing on the plot of Giacomo Puccini’s opera Madama Butterfly, Claude-Michel Schönberg’s and Alain Boublil’s musical Miss Saigon tells the story of U.S. Marine Sergeant Chris Scott and Vietnamese bargirl Kim, who met at the Dreamland bar and brothel in Saigon in April 1975, just before Saigon fell to the North Vietnamese. Dreamland is owned by a corrupt man known only as the Engineer. With lyrics by Boublil and Richard Maltby Jr., the musical premiered at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, London, on September 20, 1989, and continued its run for more than 10 years, closing on October 30, 1999, after 4,092 performances. It opened on April 11, 1991, at the Broadway Theatre on Broadway. It was staged in many cities around the world and revived in 2014 in London.

In the musical, Chris and Kim spend a night together at Dreamland and fall in love. Chris promises to take Kim to America with him, but the story then advances three years, revealing that Chris is in the United States with his wife Ellen and Kim is hiding out with her son Tam, Chris’ child, dodging the North Vietnamese authorities. Kim’s cousin, Thuy, to whom she had been betrothed and who is now a commissar in the Communist government, commissions the Engineer to find Kim and bring her to him. The Engineer succeeds in arranging a meeting, but Kim ends up killing Thuy to protect her son, and she, Tam, and the Engineer escape to Bangkok.

In the United States, John, an ex-Marine who was Chris’ friend and who took him to Dreamland on that fateful night, is working to connect the children fathered by Americans in Vietnam with their fathers. He finds out that Kim is alive and that she has a son, and he shares this news with Chris. When Chris, Ellen, and John travel to Bangkok, Kim races to his hotel, hoping he will take her and their child back to America, but her hopes are dashed when she meets Ellen and learns that Chris is married to her. Kim tells Ellen about Tam and begs her to take the child back to the U.S., but Ellen refuses. In her grief, Kim shoots herself and dies in Chris’ arms, leaving Tam orphaned.

Children like Tam, who were fathered during the Vietnam War by American GIs, were known by the Vietnamese as “children of the dust,” and were generally unwanted by both their mothers and the government. As Saigon fell, President Ford planned to evacuate 2,000 orphans, but the first flight crashed, killing 144 people, most of them children. Operation Babylift continued, however, and evacuated more than 110,000 refugees.

The exact number of Amerasians–children born to Asian mothers and American fathers–is not known, but advocacy organizations estimate that between 20,000 and 30,000 were born between 1962 and 1975. Today, the organization Amerasians Without Borders uses DNA testing to look for the less than 1,000 Amerasians still believed to be in Vietnam. DNA has also been used to reunite orphaned children with their parents.

In London, the opening of Miss Saigon met immediate protest over the casting of White actors as Asians, particularly Jonathon Pryce as the Engineer and Keith Burns, who wore prosthetics to change the shape of their eyes and bronzing cream to darken their skin. Critics also complained that the musical was racist and misogynistic, portraying Asian women as weak and powerless in a world where white people held all the cards.

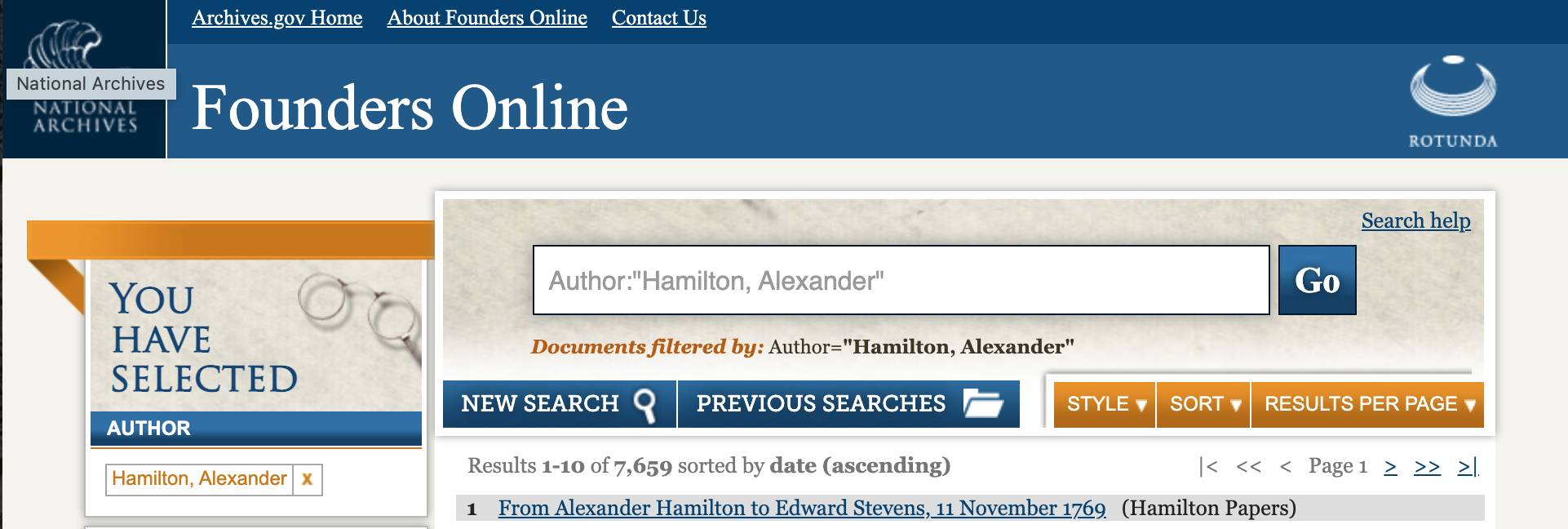

Encore: Hamilton

You can read the papers of Alexander Hamilton, including the Federalist Papers,

in the National Archives at Founders Online.

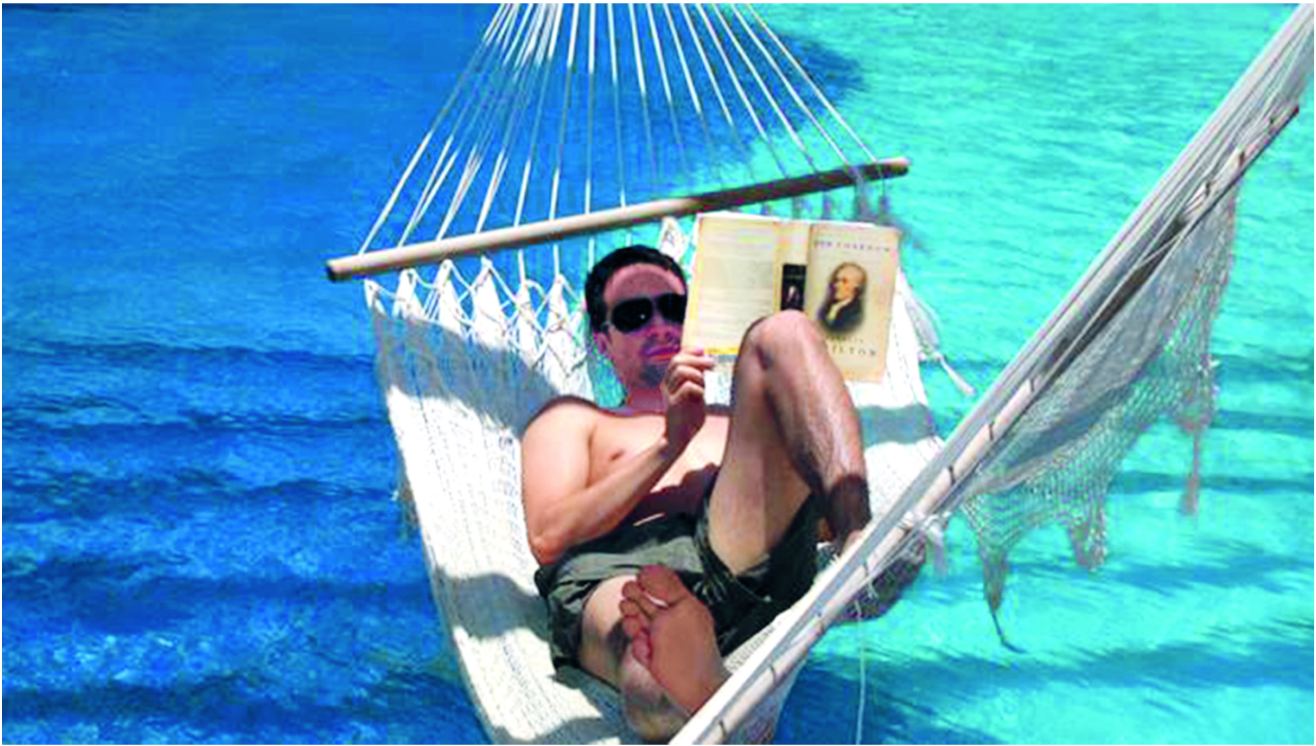

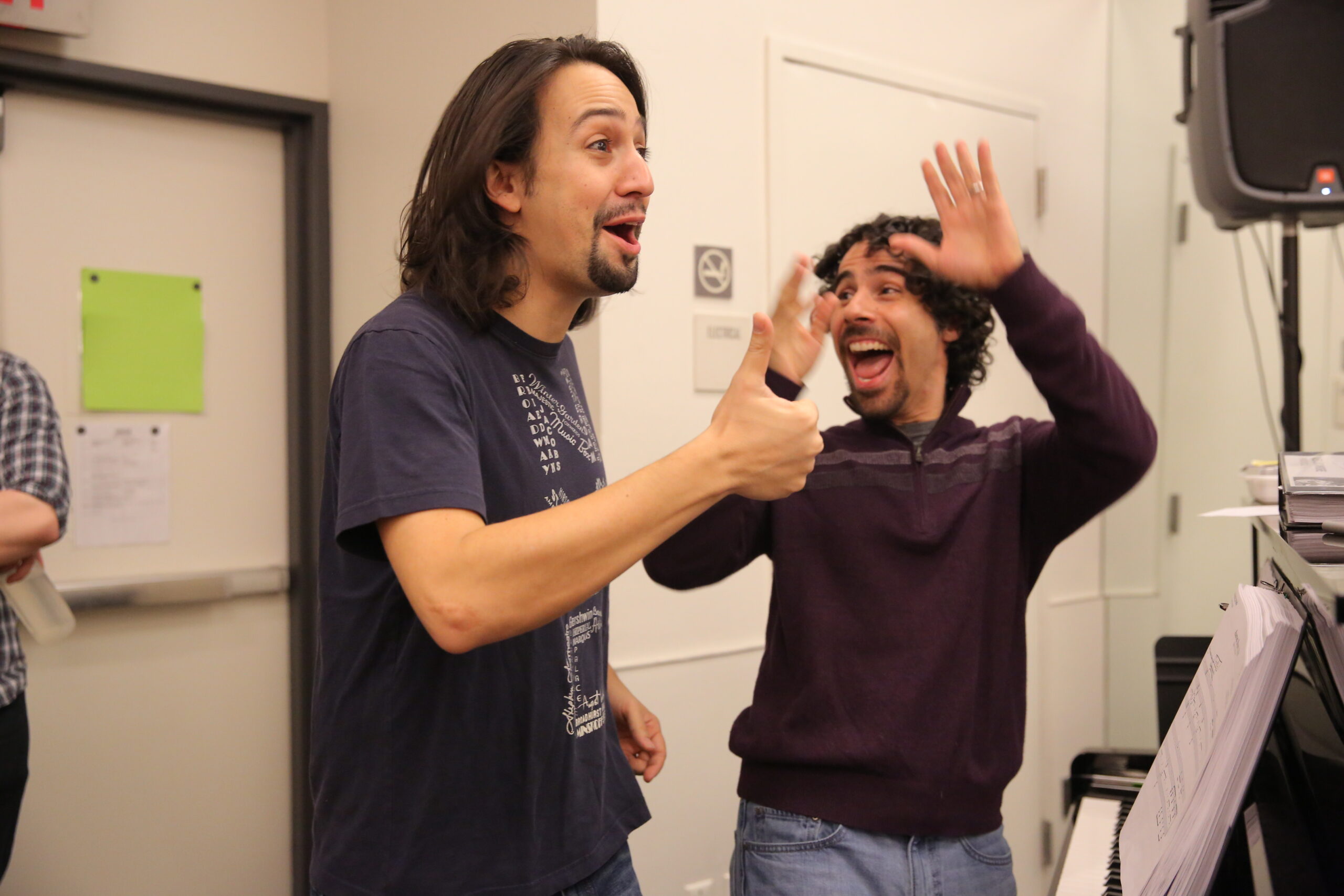

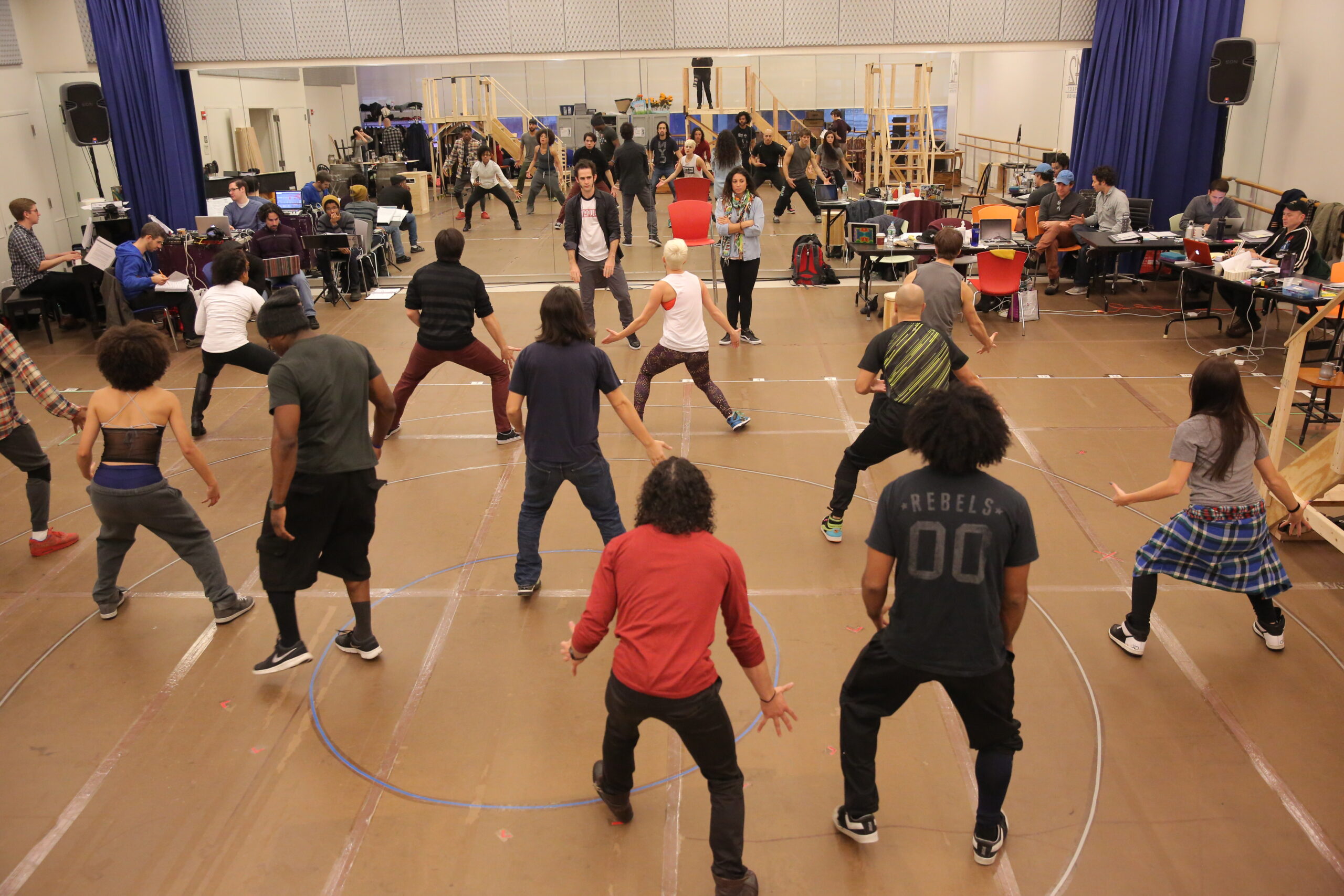

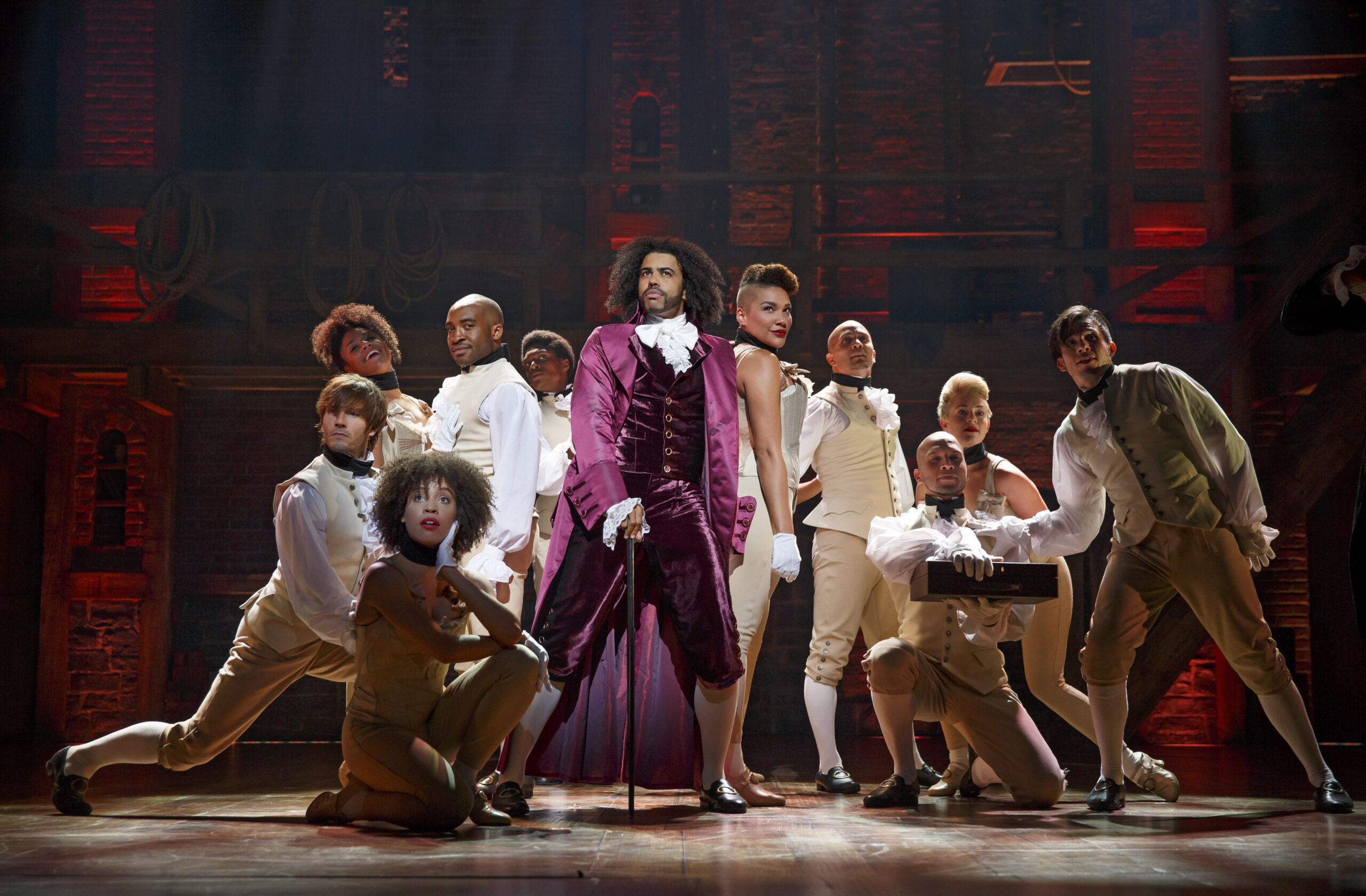

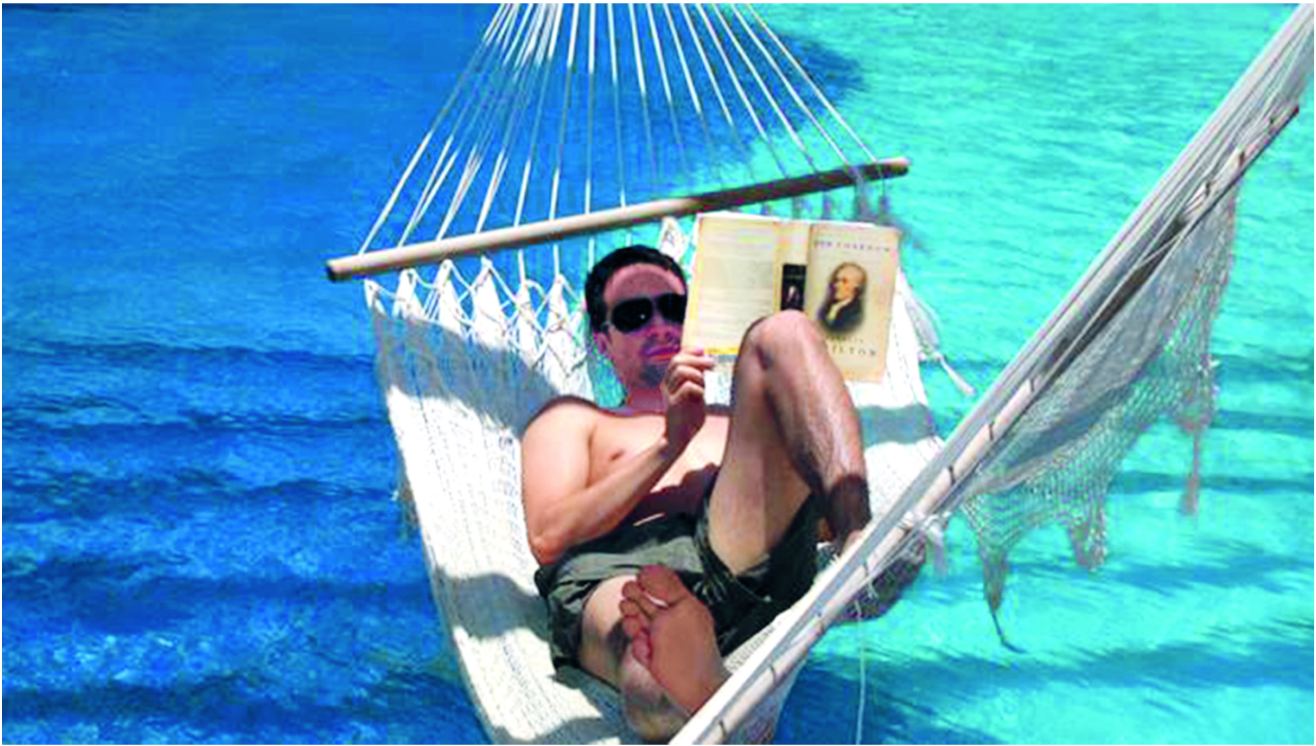

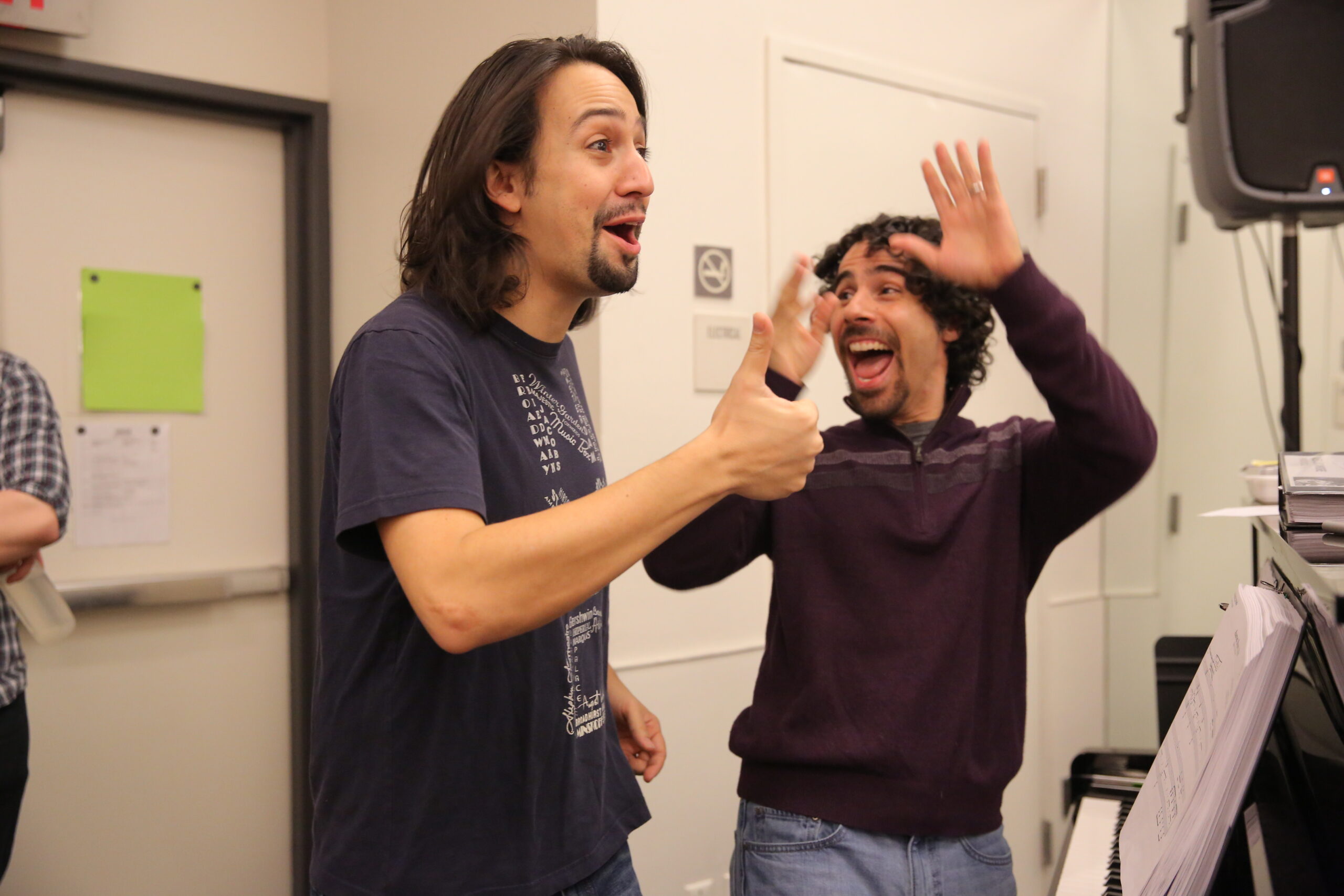

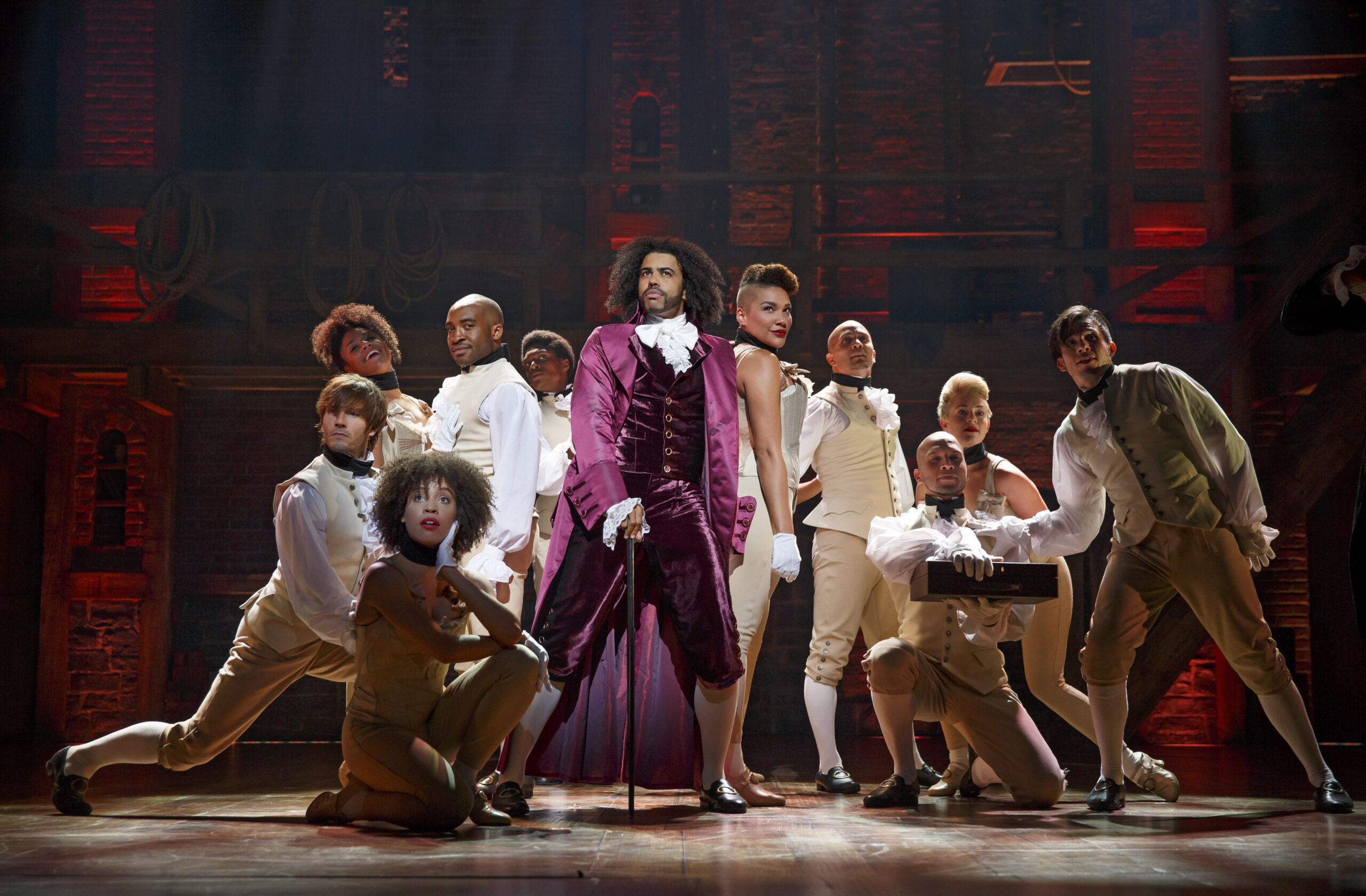

Although Hamilton is quite faithful in its retelling of the life story of founding father Alexander Hamilton, it goes completely off the track of the typical Broadway musical in nearly every other conceivable way. Based on Ron Chernow’s 2004 book Alexander Hamilton, and with music, lyrics, and book by Lin-Manuel Miranda, Hamilton features hip hop, soul, pop, show tune, and rap music, and non-White actors playing the parts of historical figures from the colonial period. It’s all quite innovative.

Hamilton premiered off-Broadway in Lower Manhattan at the Public Theater on February 17, 2015, and then opened on August 6, 2015 at the Richard Rodgers Theatre on Broadway. It won 11 Tony Awards that year, including Best Musical, and also won the 2016 Pulitzer Prize for Drama. A production of Hamilton opened in Chicago at the CIBC Theatre in October 2017; another opened in London’s West End at the Victoria Palace Theatre in London on December 21, 2017. The musical has toured the U.S. three times; the third began in Puerto Rico, with Miranda returning to play Hamilton.

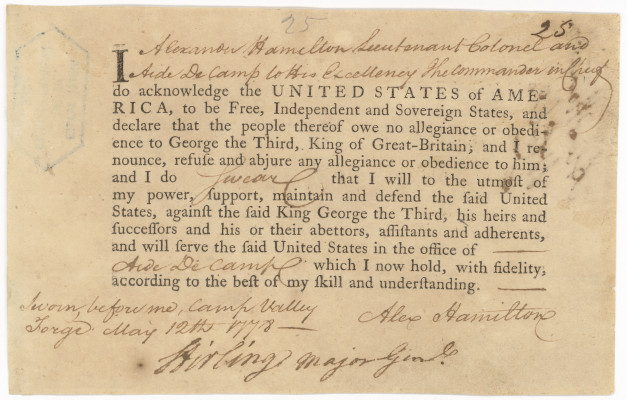

In the musical, the orphan Alexander Hamilton leaves his home on the Caribbean island of Nevis for King’s College in New York through the generosity of his neighbors, who believe in his abilities. In New York, in 1776, he met Hercules Mulligan, John Laurens, Aaron Burr, and the Marquis de Lafayette. When the Revolutionary War begins, George Washington offers Hamilton a position as his aide-de-camp, and Hamilton accepts it. He swiftly marries Eliza Schuyler, daughter of a wealthy gentleman, Philip Schuyler.

Hamilton’s loyalty oath

Meanwhile, the Marquis de Lafayette talks France into supporting the colonies against Britain. Hamilton takes part in a duel and Washington fires him for it, but Lafayette also manages to persuade Washington into rehiring Hamilton because the Battle of Yorktown was looming. Washington acquiesces, but cautions Hamilton to not try to get himself killed in an act of needless heroism. At the battle, Hamilton and Lafayette join forces to defeat the enemy, effectively ending the war.

After the war, Hamilton’s contributions include writing the majority of The Federalist Papers and becoming secretary of the treasury. In 1789, he works out a compromise that resolved a deadlock in Congress, which could not agree on whether the national government should pay the debts the states had accrued in paying for the Revolutionary War. In “The Room Where it Happens,” Hamilton, Jefferson, and Madison hammer out the Compromise of 1790, in which Jefferson and Madison accede to Hamilton that the federal government would pay the states’ debts, and Hamilton agrees that the national capital would be moved to the South, to what is now called the District of Columbia.

Motion from Alexander Hamilton to re-ratify the Constitution

Despite his meteoric rise, Hamilton experiences just as rapid of a fall when his affair with Maria Reynolds comes to light. Looking to further Hamilton’s misconduct, Jefferson, Madison, and Burr accuse him of using federal funds to pay off James Reynolds, Maria’s husband, to keep the affair quiet. Hamilton refutes this publicly in a letter he writes, “The Reynolds Pamphlet,” which ruins his reputation and relationship with his wife.

When Hamilton endorses Jefferson in the election of 1800, his long-time sometimes collaborator, sometimes rival, Aaron Burr is infuriated. He challenges Hamilton to a duel. They go to New Jersey, where Burr kills Hamilton. The musical ends with members of the cast reflecting on how Hamilton will be remembered.

Motion from Eliza Hamilton to Congress to publish Alexander Hamilton’s writings

In 2016, the National Archives Foundation honored the creators of Hamilton with our highest honor: the Records of Achievement Award. Ron Chernow, the author and historian of Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Kail, the show’s director, and Lin-Manuel Miranda, the show’s creator, were all present at the National Archives for the red carpet event, where the three of them spoke about how history came alive on Broadway. Because Hamilton himself would “write like he’s running out of time,” the team had excellent archival and primary source records to draw on for both the book and musical.

Conversation with Chernow, Kail, Miranda, and Mead: 2016 Records of Achievement Award Ceremony

(42 minutes 12 seconds)

Source: National Archives Foundation YouTube channel

View this profile on InstagramNational Archives Foundation (@archivesfdn) • Instagram photos and videos

Related Content