All American Opening

What an opening weekend of college football! The US Open has enjoyed Serena buzz and upsets. The NFL opens up this week, and the National Archives sports season starts in 10 days.

Wait, what?! The National Archives has sports stuff? Yes! The opening of the National Archives’ newest exhibit, All American: The Power of Sports, is Friday, September 16. This is a first-of-its-kind exhibition for the Archives as we explore the sports holdings, documents, photographs, film, and objects – many of which have never been on public view before.

Whether you are playing, coaching, or cheering on our favorite teams or athletes, sports have the power to bring us together as a nation. If you love an underdog (hello, Miracle on Ice) or a comeback story (the first baseball game in NYC after 9/11), this exhibition offers visitors a historical perspective on some of our iconic successes, lesser-known moments, and how athletes have used their voices over the years to flex on injustice in our society.

No matter how you visit our exhibition, whether in person, at a program, or by exploring online, we hope you’ll join us to replay some of the greatest moments in our nation’s sports history.

Patrick Madden

Executive Director

National Archives Foundation

PS – No matter how sporty we get, sadly, some rules at the Archives won’t change: No tailgating outside the Archives!

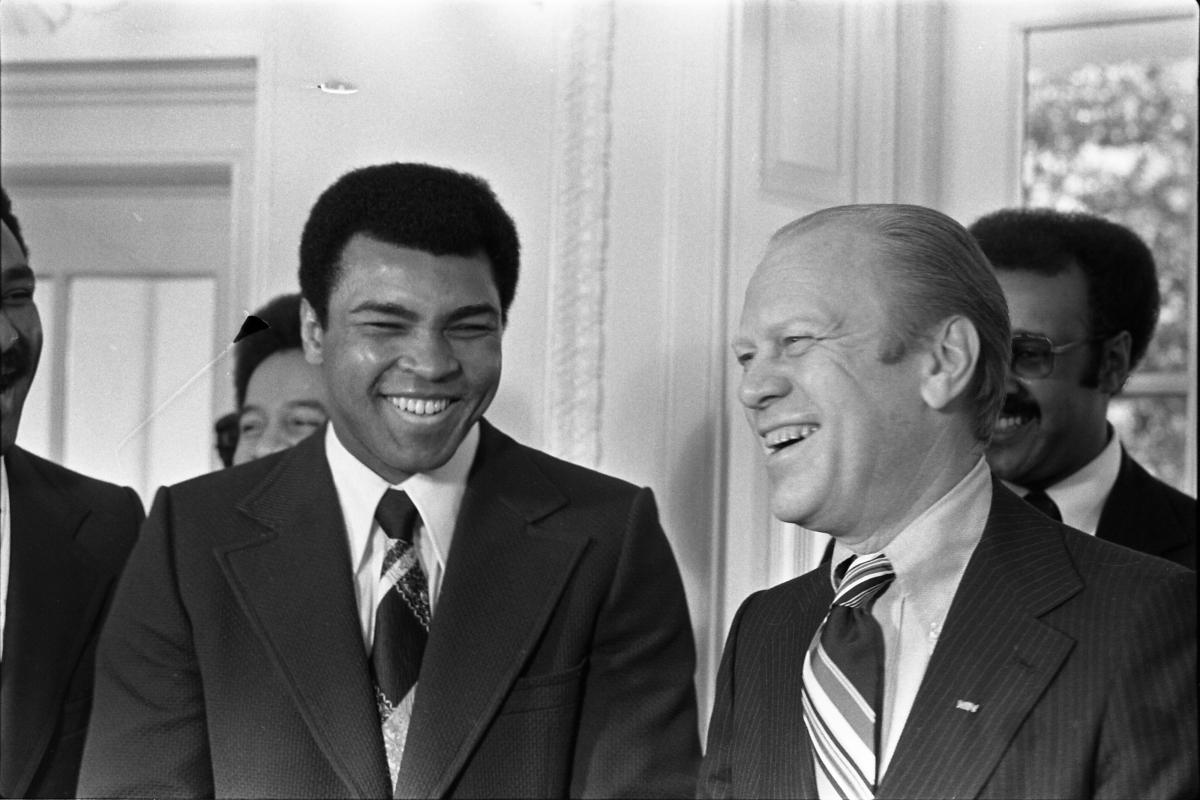

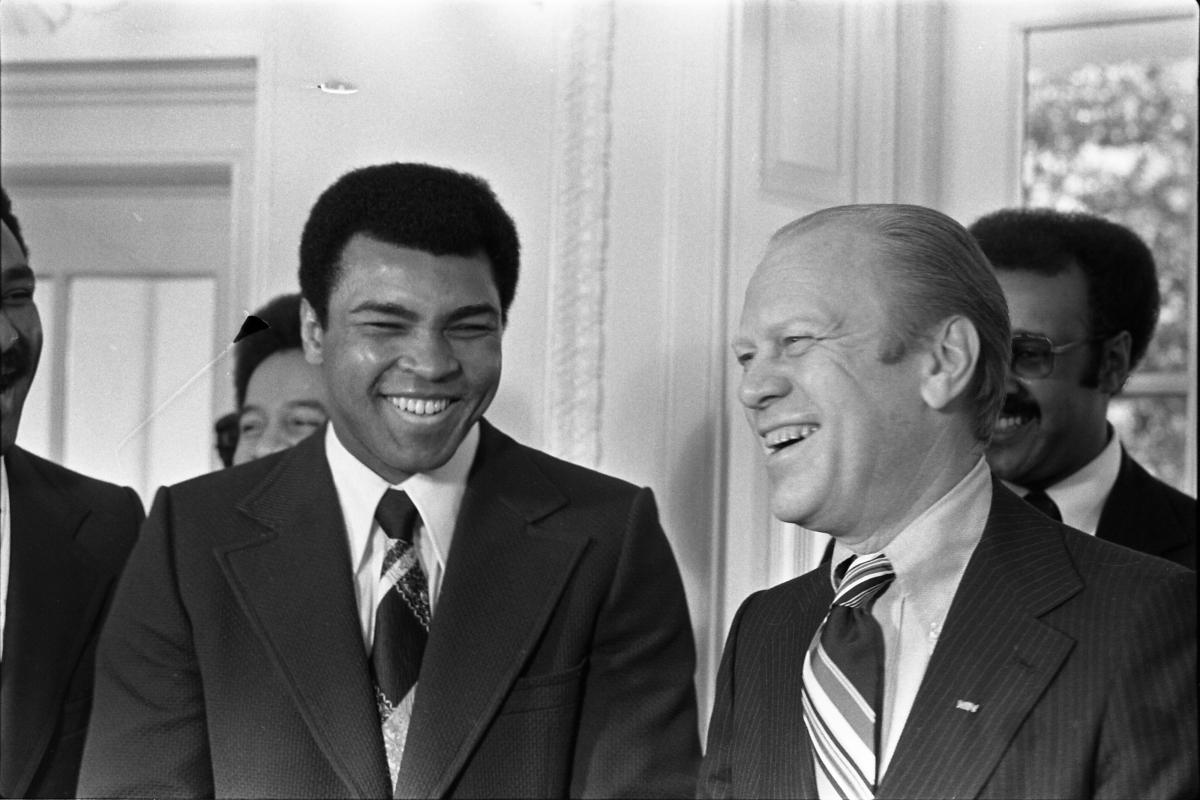

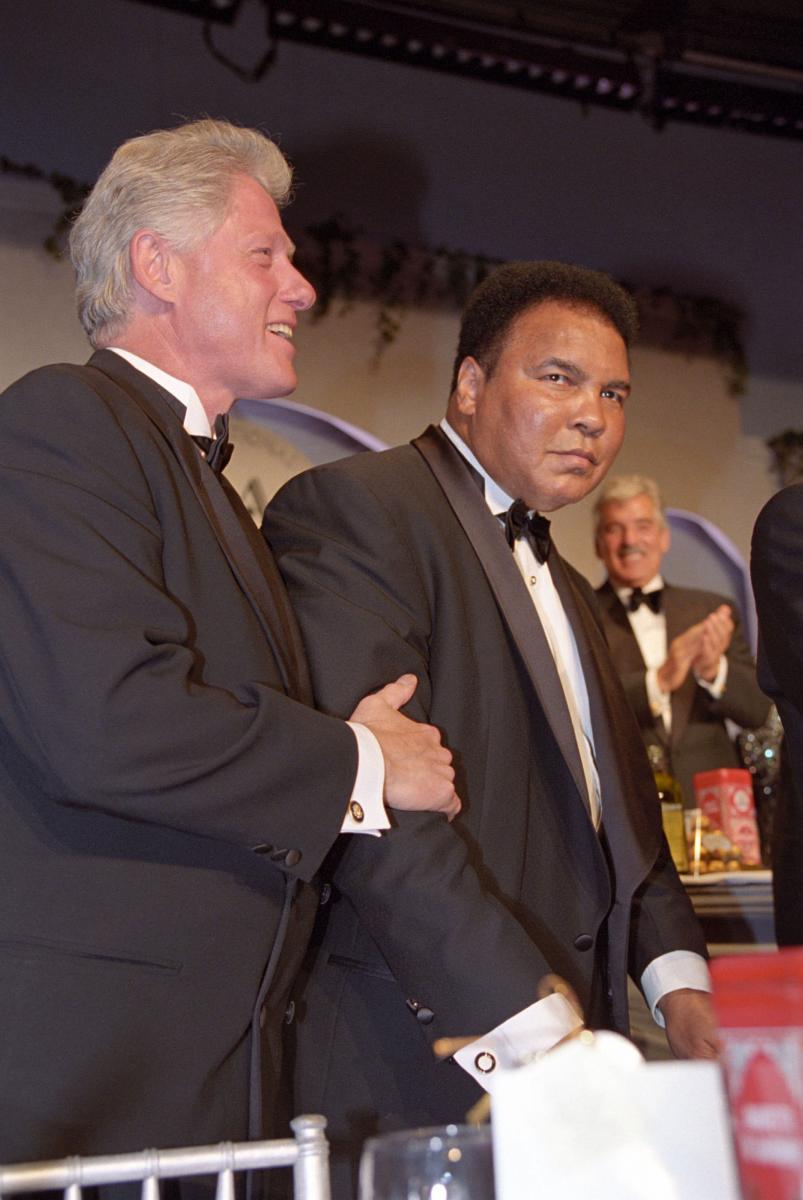

The Toughest Round

The U.S. Government’s case against Ali

National Archives Identifier: 117689259

Cassius Marcellus Clay, Jr., was born in Louisville, Kentucky, on January 17, 1942. His father, Cassius Marcellus Clay, Sr., was a billboard and sign painter, and his mother, Odessa O’Grady Clay, worked as a domestic. In Louisville, the Clay family experienced the realities of segregation in the Jim Crow South, and Cassius, Jr., was deeply affected by the murder of Emmet Till in 1954.

Clay began boxing at about the age of twelve and made his amateur debut, which he won in a split decision, in 1954. Over the next six years, he won six Kentucky Golden Gloves titles, two national Golden Gloves titles, and an Amateur Athletic Union national title. At the 1960 Summer Olympics in Rome, Clay won the gold medal in the light heavyweight division.

Clay came home to the United States and turned professional. In three years, his record was 19-0 with 15 knockouts. He also earned a reputation for trash talking his opponents. Then in 1964, Clay defeated heavyweight champion Sonny Liston and claimed the heavyweight title. He then converted to Islam, joined the Nation of Islam, which was led by Elijah Muhammad, and changed his name to Cassius X and then to Muhammad Ali.

The war in Vietnam was escalating by then. Ali had registered for the draft in 1962, but he had been classified as 1-Y (fit for service only in times of national emergency) because he was dyslexic and consequently, his spelling and writing didn’t meet the Army’s standards. In 1966, the Army lowered its standards, and Ali was classified 1-A. Ali then declared he was a conscientious objector and that he would not serve. He stated that unless Allah or Elijah Muhammad declared a war, he was not called to fight in one.

“Man, I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong,” Ali said. He later asked, “Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go ten thousand miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on brown people in Vietnam while so-called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs and denied simple human rights?” He showed up for his induction in Houston, but he refused to step forward when his name was called three times. That day, the New York State Athletic Commission stripped him of his title and suspended his boxing license.

Ali was tried and convicted of violating the Selective Service laws on June 20, 1967. He appealed the convictions all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. While his appeal worked its way through the courts, Ali went on a speaking tour of colleges and universities. Although he was soundly condemned in the media and by many older Americans for refusing to fight, he became wildly popular with young people who were opposed to the Vietnam War.

On June 28, 1971, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Ali’s conviction in a unanimous 8-0 decision. He had returned to the boxing ring in October 1970 after the City of Atlanta Athletic Commission had granted him a boxing license. The New York State Boxing Commission restored his license in September 1971, and Ali began the slow process of reclaiming his heavyweight championship title, which culminated when he defeated George Foreman in the “Rumble in the Jungle” in Kinshasa, Zaire, on October 30, 1974.

Muhammad Ali called himself “the greatest,” and many agree that he was the greatest heavyweight champion in boxing history, but his personal conviction that convinced him to going to war was wrong cost him four years in the prime of his career. That he stood by his decision through the long court battle and then won back his title speak to both the strength of his beliefs and his profound physical gifts.

To view the text of a document or the full image, click on the image displayed above

Over the Line

Althea Neale Gibson was born in Silver, South Carolina, on August 25, 1927, to Daniel and Annie Bell Gibson, who were sharecroppers. When the Great Depression hit the South, the Gibsons moved their daughter to Harlem in 1930, where their son and three more daughters were born. By participating in a Police Athletic League program, Gibson learned to play paddle tennis, and in 1939, she was the women’s paddle tennis champion for New York City at the age of twelve.

Gibson dropped out of school at thirteen and left home to get away from her abusive father. A group of her neighbors collected money to buy her a membership at the Cosmopolitan Tennis Club in Harlem so she could take tennis lessons there. In 1941, she won the American Tennis Association (ATA) New York State Championship. She went on to win several more ATA championships, which attracted the attention of Walter Johnson, a doctor who was active in the tennis community in Lynchburg, Virginia. Johnson sponsored Gibson (he later also mentored Arthur Ashe), and with his help, she improved her game and gained access to the United States Lawn Tennis Association (USLTA). In 1949, she entered Florida A&M University on a full athletic scholarship.

Although officially the USLTA (later the USTA) forbade racial discrimination, the organization neatly sidestepped the issue because most of the clubs where elite competitions were held only allowed whites to play at them. It took intensive lobbying by her fellow players and ATA officials before Gibson was invited to play at the U.S. National Championships (now the U.S. Open) at Forest Hills in Queens, New York, in 1951. She lost a hard-fought battle in the second round to Louise Brough, the reigning Wimbledon champion, but in stepping on the courts in Queens, she kicked the doors down that had kept Black players off them forever.

Gibson went on to win fifty-six national and international singles and doubles titles, including eleven Grand Slam titles: five singles, five doubles, and one mixed doubles. She retired in 1958 because amateur tennis was just that—an amateur sport that paid its participants nothing. She went on to work as a singer and an actor and played golf on the Ladies Professional Golf Association tour. In the 1970s, she managed parks and recreation commissions in New Jersey and ran unsuccessfully for public office.

In 1971, Evonne Goolagong, an Aboriginal Australian woman, became the first nonwhite woman to win a Grand Slam championship—fifteen years after Althea Gibson’s last victory. Serena Williams became the first Black woman to succeed her some forty-three years later, in 1999, when she won the U.S. Open for the first time.

“I am honored to have followed in such great footsteps,” wrote Venus Williams of Althea Gibson on Thought.co in 2003. “Her accomplishments set the stage for my success, and through players like myself and Serena and many others to come, her legacy will live on.”

Althea Gibson: Tennis Champion

– a short biographical film

(10 minutes 58 seconds)

National Archives Identifier: 49457

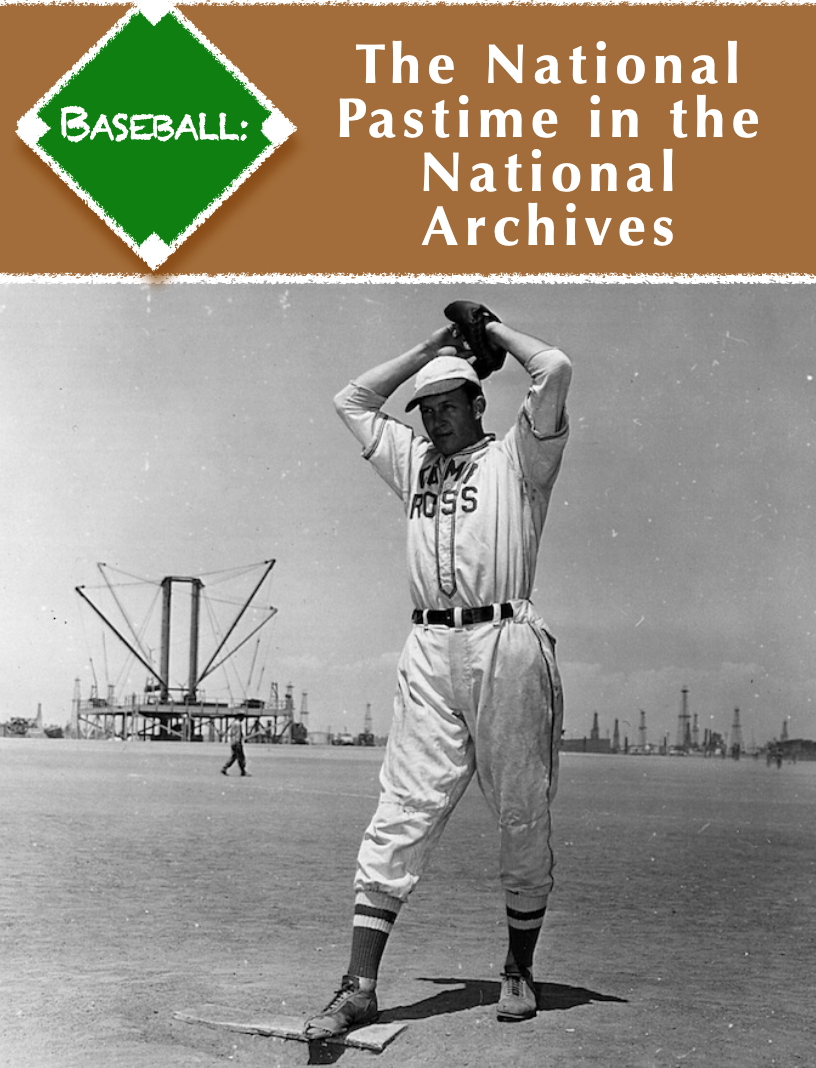

A League of Their Own

The National Pastime in the Archives

NARA Publications

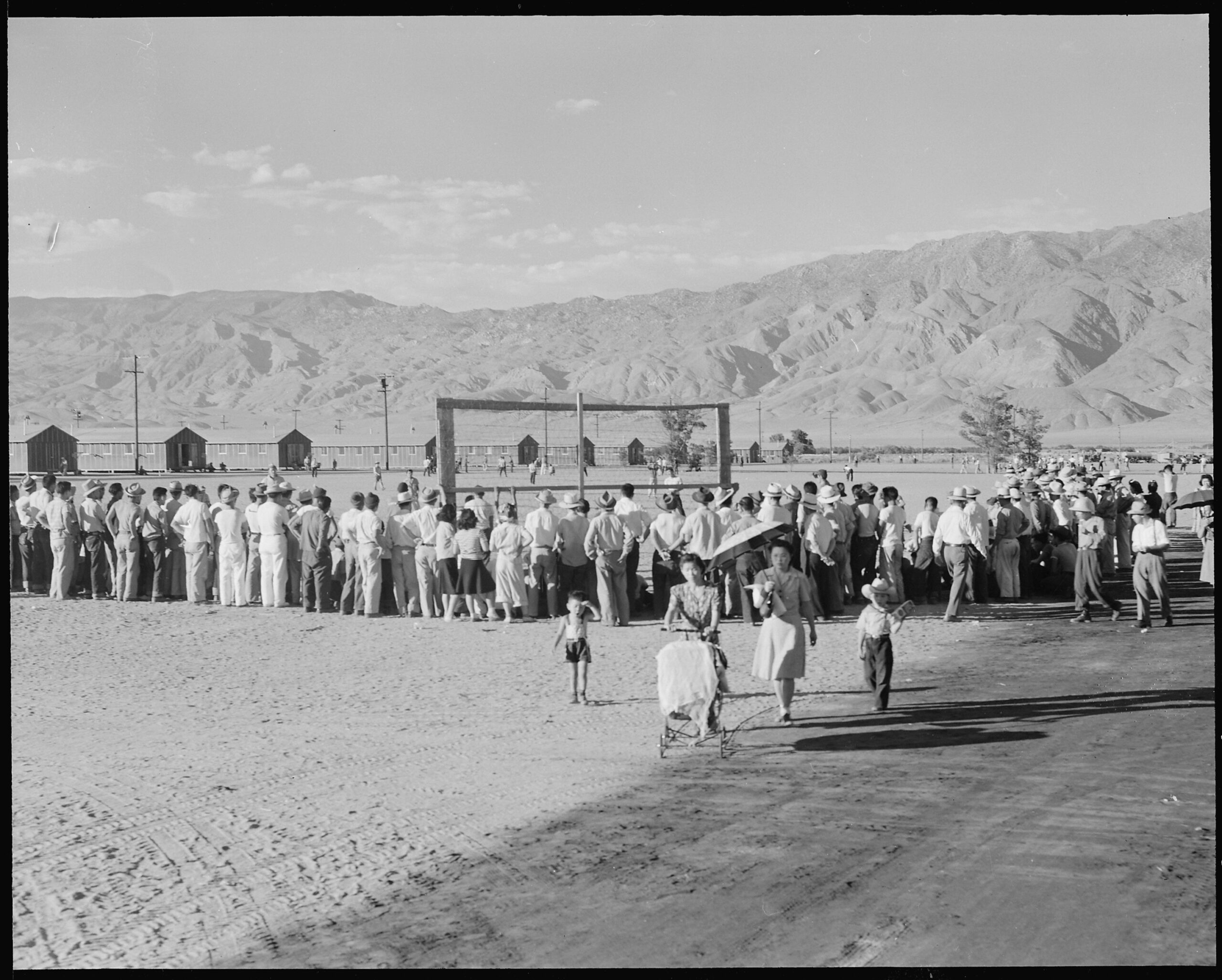

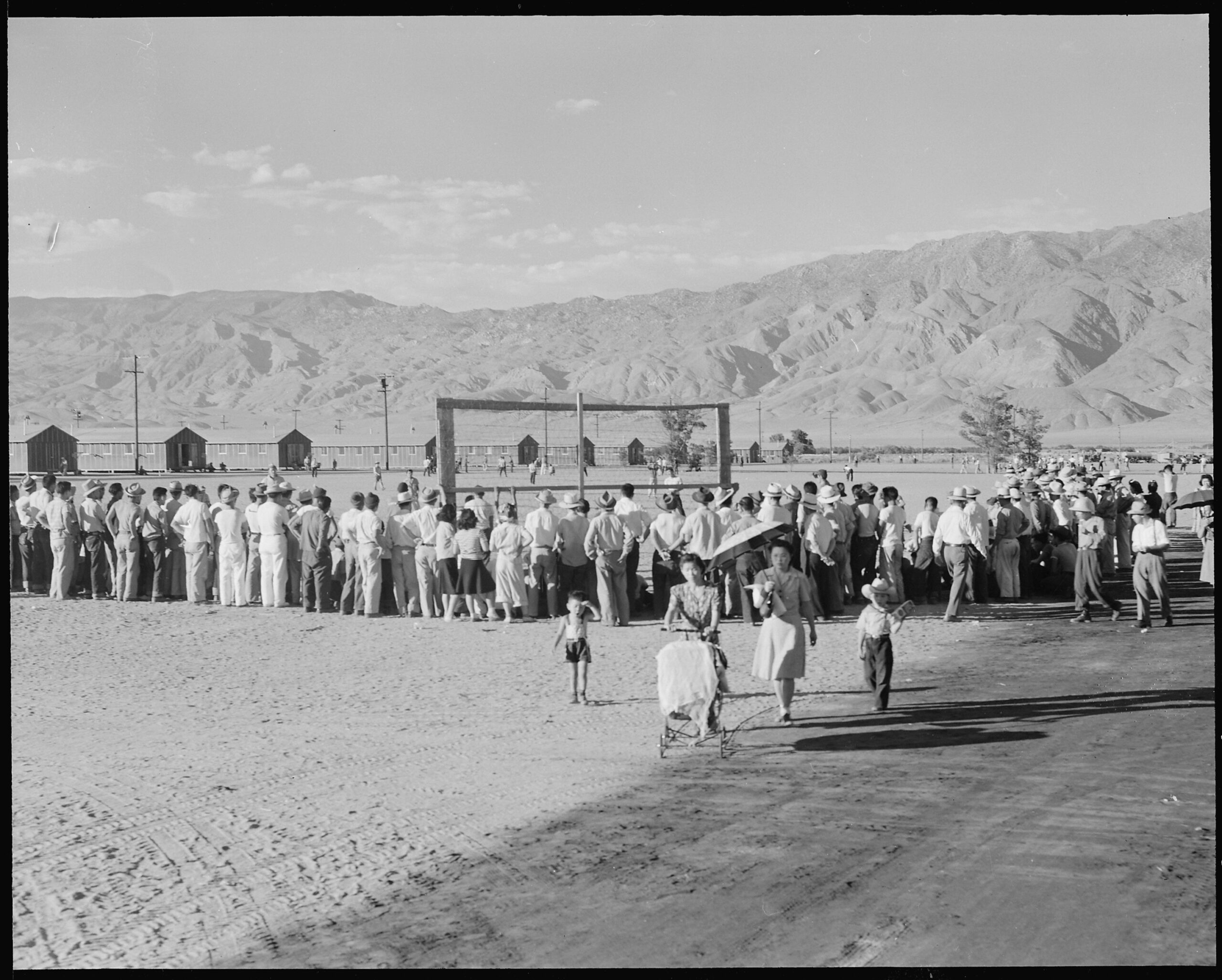

Americans have played America’s pastime in all kinds of circumstances. After World War II began, Japanese Americans were removed from their homes and placed in internment camps. Once there, they did their best to make their dismal surroundings as comfortable as possible. At several of the camps, they started playing baseball, which helped them emphasize that they were Americans, not foreigners.

To view the text of a document or the full image, click on the image displayed above

EX(S)PORTS

Love of Sport – Czechoslovakia

National Archives Identifier: 44268007

The United States Information Service (USIA) was the nation’s overseas public relations operation, aiming, according to its mission statement, “to understand, inform and influence foreign publics in promotion of the national interest, and to broaden the dialogue between Americans and U.S. institutions, and their counterparts abroad.” President Dwight D. Eisenhower established the USIA in 1953, and it operated until 1999. Its principal function was to combat the spread of communism throughout the world and to offset negative propaganda about the United States that communist states were spreading. The USIA used four mechanisms: broadcasting information; motion picture service; press service; and libraries and exhibitions.

Sports in the USA

National Archives Identifier: 6949097

Sports in the USA – Philippines

National Archives Identifier: 6949098

The agency created and distributed millions of posters, including this one, which extols the value of sports in the United States and connects the spirit of fair play with everyone worldwide who enjoys sports.

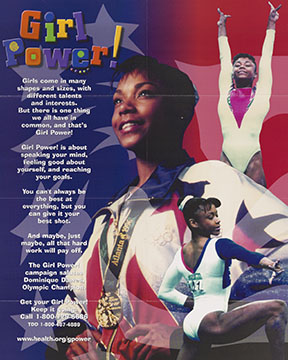

Girl Power!

Girl Power Poster

Dominique Dawes was twelve when she became the first Black woman on the U.S. women’s Olympic gymnastics team in 1988. In 1996, she was a member of the “Magnificent Seven” Olympic gymnastics team that won the first gold team medal for the United States.

And it seems that Black women aren’t done making history in gymnastics just yet! On August 21st, 2022, all three gymnasts on the podium at the U.S. Gymnastics Championships were Black women. They are continuing the legacies of greats like Dominique Dawes, Gabby Douglas, and Simone Biles.

Konnor McClain, Shilese Jones, Jordan Chiles at the 2022 U.S. Gymnastics Championships

Photo credit: Mike Ehrmann via Getty Images