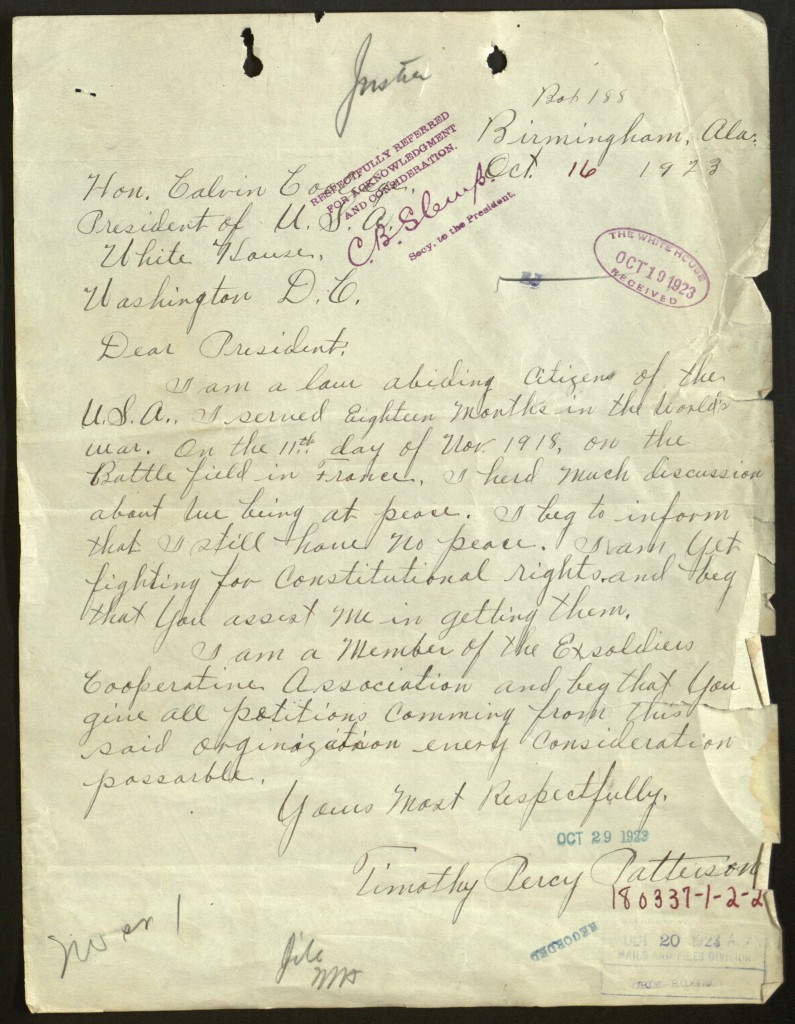

Nearly five years after the end of World War I, African-American veteran Timothy Percy Patterson wrote to President Calvin Coolidge. “I served eighteen months in the World’s War. On the 11th day of Nov. 1918, on the Battlefield in France I heard much discussion about we being at peace. I beg to inform that I still have no peace.” Patterson was one of nearly 400,000 African-American men who served in the U.S. military during World War I. Approximately 200,000 of these were sent to Europe. However, these same soldiers had come of age in a society that increasingly sought to limit their right to vote and to segregate them into separate and unequal public facilities.

Nearly five years after the end of World War I, African-American veteran Timothy Percy Patterson wrote to President Calvin Coolidge. “I served eighteen months in the World’s War. On the 11th day of Nov. 1918, on the Battlefield in France I heard much discussion about we being at peace. I beg to inform that I still have no peace.” Patterson was one of nearly 400,000 African-American men who served in the U.S. military during World War I. Approximately 200,000 of these were sent to Europe. However, these same soldiers had come of age in a society that increasingly sought to limit their right to vote and to segregate them into separate and unequal public facilities.

Further, after fighting the German army in Europe, African-American veterans found themselves confronting the racial violence of lynching and a resurgent Ku Klux Klan. More than 40 years after Patterson wrote his protest letter, the federal government passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The passage of these laws was hastened by the non-violent demonstrations against the forces supporting racial segregation and black disenfranchisement during the 1950s and early 1960s. Yet, letters like that of Timothy Patterson’s remind us that this struggle has a long history that pre-dates the rise of the “modern” civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

Timothy Percy Patterson to President Coolidge, October 16, 1923.

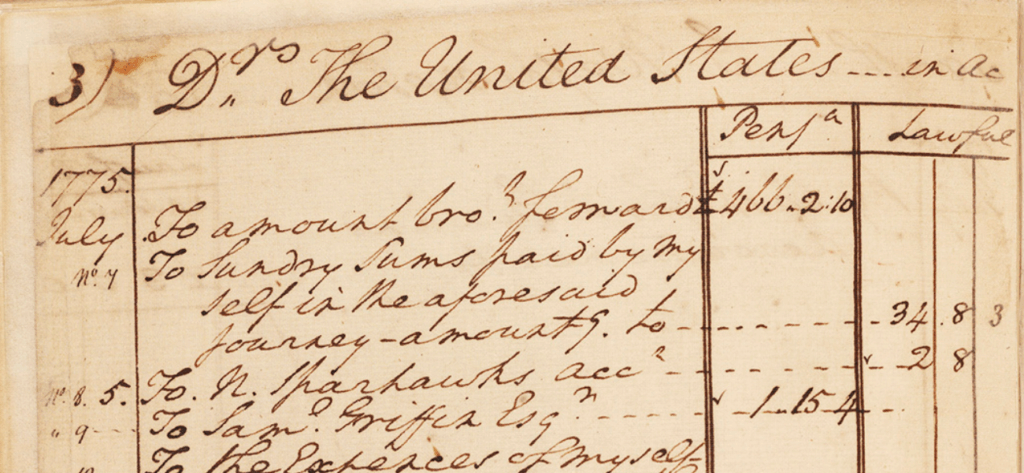

File180337-1-2-2; Straight Numerical Files;

Records of the Department of Justice, National Archives.

This document is being featured in conjunction with the National Archives’ National Conversation on Civil Rights and Individual Freedom. Click here to see more related records.

Amending America is presented in part by AT&T, Seedlings Foundation, Ford Foundation, and the National Archives Foundation.