In Transit: The Journey of The Founding Documents

In honor of the Library of Congress’s upcoming birthday on April 24, we’re taking a closer look at the early journey of the Founding Documents—including the time they spent at the world’s largest library.

On April 24, 1800, President John Adams established the Library of Congress for the purchase of “such books as may be necessary for the use of Congress.” Since then, the Library of Congress has amassed a vast collection of over 158 million cataloged books and print materials and nonclassified collections like manuscripts, maps, and audio materials.

But did you know that before coming to the National Archives, the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution called the Library of Congress home? Read on to learn more about the Founding Documents’ early travels.

The Declaration on the Road

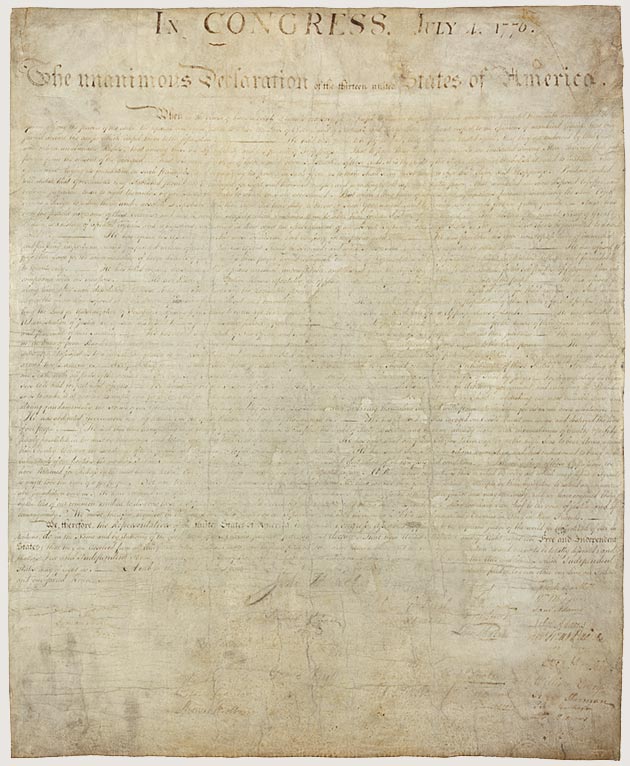

Following its signing in 1776, the Declaration of Independence moved with Congress—from city to city—throughout the Revolutionary War. Then, in September 1789, the secretary of Congress officially transferred the Declaration to the custody of the Secretary of State, and the document continued to move with the national government—from New York, to Philadelphia, and finally to Washington, D.C., in 1800.

In 1841, the Declaration was moved to the Patent Office (now the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery) to be exhibited to the public, where it was exposed to natural light, fluctuating temperatures, and humidity for 35 years. This, in combination with the document’s early travels, contributed greatly to the Declaration’s fading.

Next, in 1876, the Declaration was sent to Philadelphia to be exhibited in Independence Hall for the Centennial National Exposition before returning to Washington, D.C., in 1877. It was then placed on display at the State-War-Navy Building (now the Eisenhower Executive Office Building) next to the White House. In 1892, a new steel case was constructed and, when further exhibition was deemed unsafe for the Declaration, it was carefully wrapped and stored flat in the State Department library until 1921.

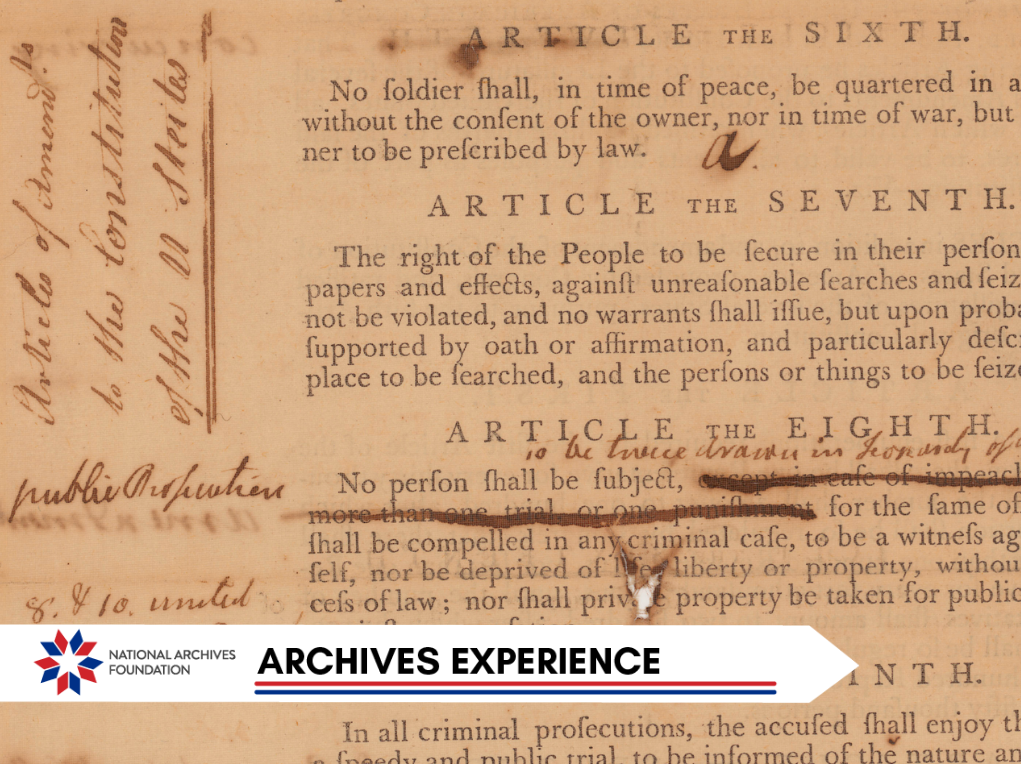

But what about the Constitution and the Bill of Rights? The Constitution, like the Declaration, was passed to the custody of the State Department in 1789 and moved with the national government. There is no record of the Constitution being exhibited before 1921. While there are records that the Bill of Rights was in the State, War, and Navy Building (Eisenhower Executive Office Building) in 1936, it is unclear how long it was there.

At the Library

In 1921, President Warren Harding signed an executive order transferring custody of the Declaration and Constitution from the State Department to the Library of Congress. It was here that both were put on dignified public exhibit—enshrined and kept in special encasements—for the first time in 1924. Designed by Francis H. Bacon, the shrine holding both documents was located on the second floor of the Thomas Jefferson Building. The shrine directly faced the Capitol, signifying the documents’ importance to the national government. More than two dozen supplementary documents from the Revolutionary Era were also displayed, along with portraits of signers of the Declaration and the Constitution and their biographies.

Shrine for the Charters of Freedom at the Library of Congress, 1952

A Permanent Home

After the groundbreaking of the National Archives building in 1931, President Herbert Hoover announced that "the most sacred documents of our history—the originals of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States" would be placed on display there. However, it wasn’t until 1952 that all three Founding Documents, including the Bill of Rights, were united and put on permanent public display. When World War II intervened, the Library of Congress sent the Declaration and Constitution to the bullion depository at Fort Knox, Kentucky, for safekeeping.

On December 13, 1952, the Declaration and the Constitution were transferred from the Library of Congress via a formal military procession to join the Bill of Rights in the National Archives Rotunda, where all three of the Founding Documents would be displayed together for the first time.

The Chief Justice of the United States presided over the formal enshrining ceremony on December 15, where more than 100 officials of national civic, patriotic, religious, veterans, educational, business, and labor groups assembled in the Rotunda and listened as President Harry Truman announced that the Charters of Freedom” were now assembled in one place for display and safekeeping.

Chief Justice Fred N. Vinson delivering the closing remarks at the enshrining ceremony, 1952

The Founding Documents Today

The Founding Documents are viewed in the National Archives Rotunda by more than a million visitors annually. To safely display the Founding Documents, the National Archives exhibits them at low light levels and in specially built metal and glass encasements. All three documents underwent conservation treatment in 2003 and were placed in new, state-of-the-art encasements. While the 1950s-era encasements were filled with helium to provide an environment free of oxygen, the 2003 encasements use argon gas to prevent document deterioration. The National Archives monitors the oxygen levels of the Founding Document encasements.

Today, it’s only at the National Archives in Washington, DC, where you can see the original Charters of Freedom for yourself—preserved, protected, and shared for generations to come.

Related Content