Remembering President Jimmy Carter

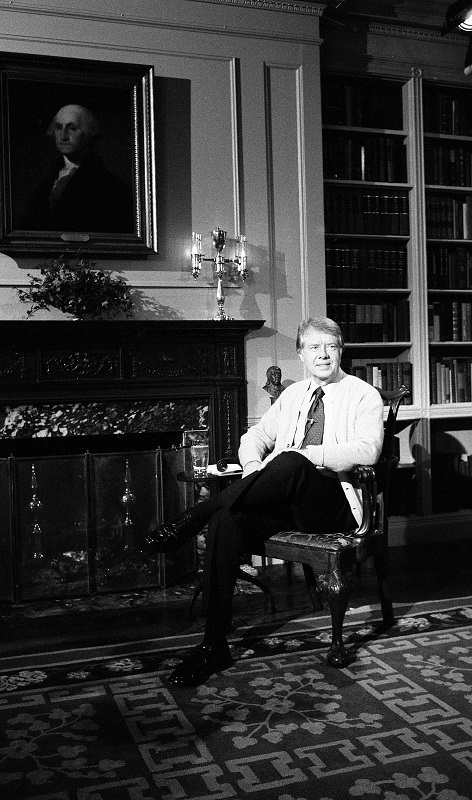

The National Archives Foundation fondly remembers President Jimmy Carter, a champion of peace, human rights, and service. From the Camp David Accords to Habitat for Humanity, he leaves behind a legacy of compassion and global cooperation.

If you had an entire library dedicated to your life’s work and legacy, what would be in it?

It’s a hypothetical question for most of us, but for presidents, the issue of legacy looms large in their minds. Jimmy Carter was clear about his legacy:

“I’d like to be remembered as someone who was a champion of peace and human rights.”

Carter’s term in office was focused on peacemaking, both at home and in the most tense areas of the world. He continued work in global conflict resolution for decades after he left office, which earned him a Nobel Peace Prize.

Fundamental to his belief system was that the presidency or elected office were not the only places he could make a difference.

“In our democracy, the only title higher and more powerful than that of president is the title of citizen. It is every citizen’s right and duty to help shape the future legacy of our nation.”

Famously, he built houses for Habitat for Humanity, taught Sunday school and was instrumental in eradicating guinea worm disease. It’s no surprise, then, that he is considered to have had one of the most successful and productive post-presidencies in history. Above all, he was a man driven by his strong faith and desire to leave the world better than he found it.

“My faith demands that I do whatever I can, wherever I am, whenever I can, for as long as I can, with whatever I have to try and make a difference.”

A Peanut Farmer at Heart

James Earl Carter, Jr., was born at the Wise Sanitarium in Plains, Georgia, on October 1, 1924, to Bessie Lillian and James Earl Carter, Sr. His mother Lillian worked as a nurse at the Wise Sanitarium where Jimmy was born, and he was the first American President to be born in a hospital. The couple later had three younger children, Gloria, Ruth and Billy.

James Carter, Sr., was a businessman in Plains who also invested in farmland. The family moved around quite a bit before they settled on a farm near a Black settlement named Archery. Jimmy’s father was pro-segregation, but he allowed his son to befriend the children of the Black farmhands, which influenced Jimmy’s attitudes toward the Black community for the rest of his life. He attended school in Plains and graduated from high school in 1941, at the end of the 11th grade because the school didn’t have a 12th grade class. In high school, he was a member of the Future Farmers of America.

Carter studied engineering at Georgia Southwestern College and then transferred to Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta. In 1943, he was admitted to the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis, Maryland, which was the fulfillment of a lifelong dream. While he was at home in the summer of 1945 before he started his final year at the academy, he ran into Eleanor Rosalynn Smith, who was his sister Ruth’s best friend, and whom he had known his entire life, and asked her to go to the movies with him on a double date with Ruth and her boyfriend. She accepted, and when Jimmy got home that night, he told his mother he was going to marry Rosalynn. They both went back to college that fall, but they were engaged in May of 1946, and they married on July 7, 1947, after Carter graduated 60th of 821 midshipmen in the class of 1947.

Carter was a naval officer from 1947 until 1953, stationed in Virginia, Hawaii, Connecticut, California and New York. In 1948, he trained for submarine duty and subsequently served aboard the USS Pomfret and the USS K-1. He then was sent to the Naval Reactors Branch of the Atomic Energy Commission in Washington, D.C., an assignment that resulted in his being sent in mid-December 1952 on an emergency mission to lead an U.S. crew to help Canadian and other U.S. personnel dismantle the core of a nuclear reactor that had melted down at Chalk River Laboratories in Deep River, Ottawa. The painstaking procedure required the workers to don protective gear and dash in and out of the building, staying only a few minutes at a time to avoid endangering their lives. At the time, Carter was one of the few Americans qualified to undertake such an operation.

Intending to sail on the USS Seawolf, a nuclear-powered submarine that was slated for construction starting in early 1953, Carter began studying nuclear power plant operation at Union College in Schenectady, New York, but his father died that July, and he took a release from active duty to return to Plains and take over the family peanut business. The latter was in serious trouble when the Carters got back to Plains, and Rosalynn wasn’t very happy about leaving navy life behind—she later said that returning to Plains seemed like taking “a monumental step backward.” When they first arrived, the business was in terrible shape, and the Carters had to live in public housing. That first year, the peanut crop failed because of drought, but with Jimmy managing the farming end of the business and Rosalynn keeping the books, they turned the operation around and made a success of it.

Jimmy Carter Naval Academy Graduation, 1946

About this time, Carter began to speak about the racial injustices that were common in Plains and in Georgia. He and Rosalynn were active in the Baptist Church, and Carter became chairman of the Sumter County school board, where he actively promoted integration in the wake of the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown vs. Board of Education. When a Georgia state senate seat came open in 1962, Carter announced his candidacy 15 days before the election. After he challenged the vote count of the first election, it was proven to be fraudulent, and a second election was held, which Carter won.

Carter served two terms in the Georgia state senate and then ran for governor in 1966 against the segregationist Lester Maddox, who defeated him. Carter returned to Plains and planned his next campaign, which he launched in 1970.

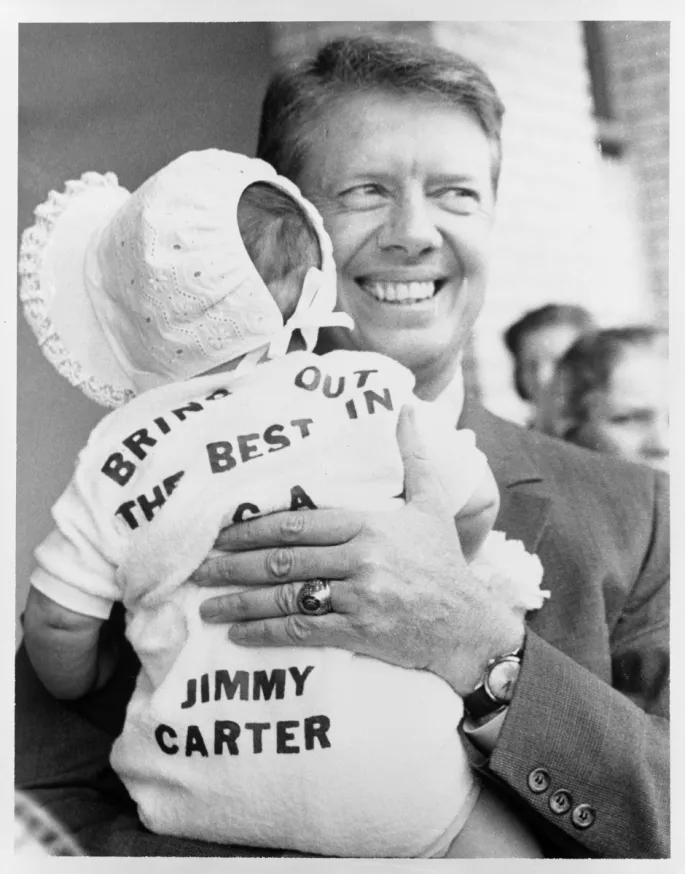

During his tenure as governor, Carter devoted himself to advancing civil rights and to reducing the size and spending of state government. He set his sights on the presidency and began to engage in national politics in 1972. In December 1974, he announced his candidacy for the presidency. Although the Democratic field was crowded with 16 contenders for the nomination, Carter eventually beat all of them out. He ran against Gerald Ford in the general election and won a hard-fought and very close election.

James Earl Carter, Jr., was sworn in as president on January 20, 1977. He immediately fulfilled one of his campaign promises by pardoning all Vietnam War draft dodgers by executive order.

Cardigans and Conservation

Carter arrived in Washington at the precise moment when the country was experiencing a flurry of dreadful economic problems: a declining dollar, high government spending that was needed to pay for the last years of the war in Vietnam and Lyndon Johnson’s public programs, low tax income brought on by the refusal of several presidents to raise taxes, high inflation, high unemployment and an energy crisis.

Furthermore, the first couple of years of the Carter administration were not legislative successes, mostly because Jimmy Carter didn’t get along very well with many members of Congress. He came to Washington as an outsider who intended to cut what he saw as the size of the federal government, pork-barrel spending and unnecessary projects, and he promptly ran afoul of the proponents of those projects, who didn’t consider them unnecessary at all. All things considered, it made for some pretty tough sledding at the beginning of his presidency.

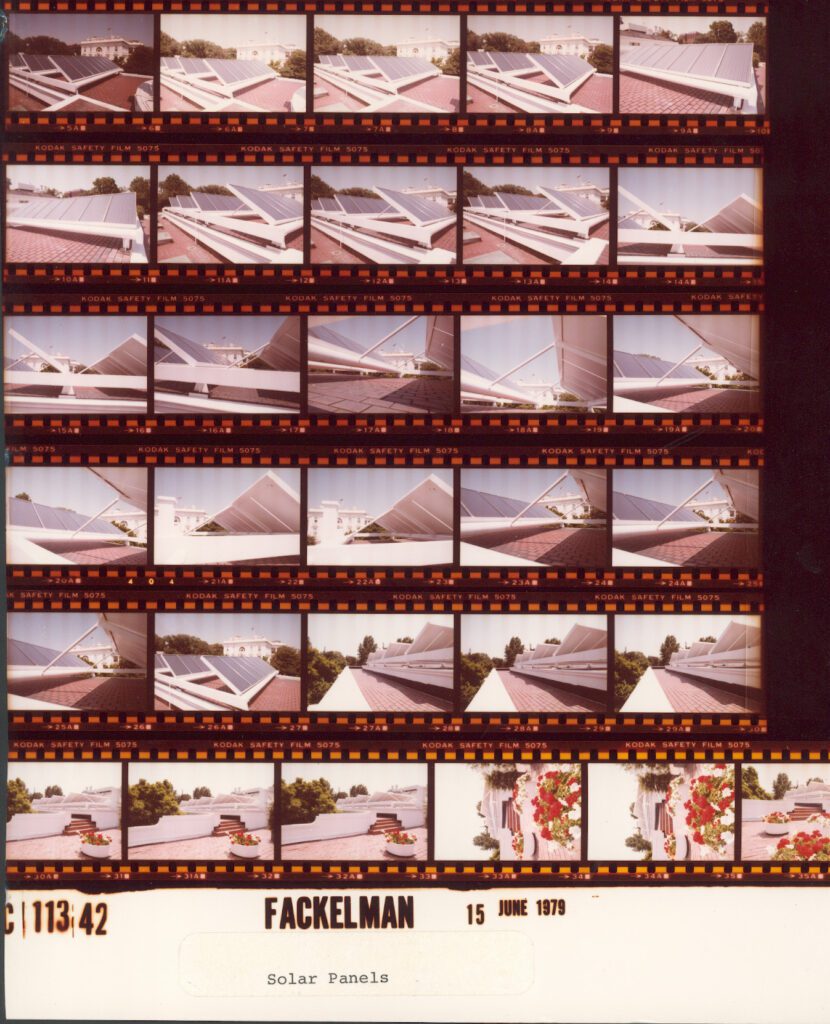

On February 2, 1979, two weeks after he was sworn in, Jimmy Carter spoke to the nation in a speech he titled “Report to the American People on Energy.” Wearing a cardigan and pointing out the extremely cold weather of that winter, he urged the creation of a comprehensive national energy policy to manage national supplies of oil and gas. He also emphasized the need for conservation rather than consumption, stating, “All of us must learn to waste less energy.” He encouraged his listeners to turn their thermostats down to 65 degrees during the day and 55 degrees at night and to drive their cars at 55 miles an hour.

Unfortunately, most Americans were more preoccupied with inflation and unemployment than national energy policy at that moment, and that included Congress. His energy bill was stuck in the legislature for more than two years.

The Peacemakers

In the thousands of years of history that play into the geopolitical landscape of the Middle East, 13 days should be a blip on the radar. But these 13 days culminated in a historic agreement that changed the landscape of Middle East politics in an attempt to bring peace.

“Baby steps” had been the motto of the former administration, led mostly by Henry Kissinger whose travel back and forth between Israel and Egypt in the aftermath of the Yom Kippur War had given rise to a new style of negotiating called “shuttle diplomacy.” Instead, Carter wanted to take on the big picture with a comprehensive approach. Even though U.S.-involved peace talks had stalled during the 1976 presidential campaign, Carter got them going again.

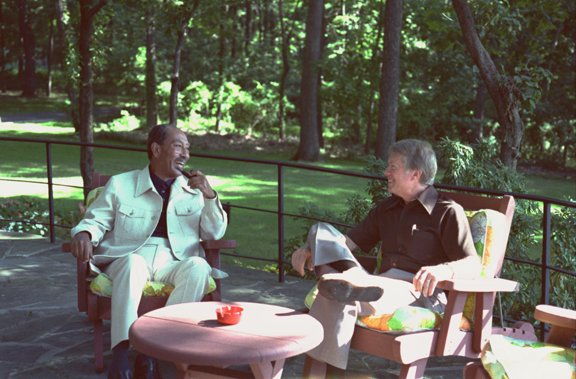

Before the end of his first year in office, Carter met with all of the necessary parties: Anwar El Sadat of Egypt, King Hussein of Jordan, Hafez al-Assad of Syria and Yitzhak Rabin of Israel. Rabin, however, was not in office long enough to see talks come to fruition because he was succeeded by Menachem Begin in May of 1977. Both Hussein and al-Assad wanted nothing to do with talks, and al-Assad consented to only meet briefly with Carter in Geneva. The framework for peace was already on shaky ground.

Thankfully, it was the Egyptian president who came to the table first, going so far as to make a speech before the Israeli parliament about what peace would look like. It was a curveball to the world, including the Carter Administration, which had planned on reviving peace talks in Geneva. Sensing an opportunity to move on the momentum of peace, Carter invited Begin and Sadat for secret negotiations at Camp David. But Begin and Sadat were hardly friends; during the talks, Carter found himself conducting his own type of “shuttle diplomacy” as he went back and forth between Begin’s and Sadat’s cabins to convey information. A shorter distance than Kissinger traveled, sure, but shuttle diplomacy nonetheless. To lessen the animosity, Carter even took both leaders to Gettysburg National Military Park, using the U.S.’ own Civil War as a mirror of their current conflict. A combination of a team of committed experts, the absence of media and the high political stakes finally led to an agreement between the two parties. The Camp David Accords were signed on September 17, 1978.

So, was there peace? Yes and no. The treaty normalized relations between Egypt and Israel and solidified both countries as U.S. allies. This had the added bonus of weakening the influence of the Soviet Union in the region. Even today, Egypt still controls the Sinai Peninsula that was ceded to them by Israel in the negotiations, Begin and Sadat shared a Nobel Prize, and these talks set a precedent for further peace agreements in the Middle East. However, the treaty was rejected by the UN because of lack of involvement from both that organization and the Palestinians. Egypt’s place in the Arab alliance was also called into question, and on October 6, 1981, Sadat was assassinated as he watched a parade.

Even post-presidency, Jimmy Carter continued to mediate conflicts around the world, including a 1994 conflict in Haiti that could have led to a U.S. invasion. Twenty-one years after leaving office, Jimmy Carter was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for “his decades of untiring effort to find peaceful solutions to international conflicts, to advance democracy and human rights, and to promote economic and social development.”

September 17, 1978 – Signing of the historic Camp David Accords

September 5-17, 1978 – Carter and Sadat at the Camp David Summit

March 26, 1979 – Carter, Sadat, and Begin join hands as they sign the “Treaty of Peace Between the Arab Republic of Egypt and the State of Israel”

Our Common Humanity

Jimmy Carter’s presidency fell at an interesting time in the country’s political landscape. The height of the Civil Rights movement had passed, and the women’s movement had kicked off at the beginning of that decade. There was still work to be done, and the Carter administration helped make these strides.

Although the height of the Civil Rights movement had passed by the time Carter was elected, the Black community was still underrepresented, especially in the federal government. This was in part rectified by Carter’s historic appointment of Azie Taylor Morton as Secretary of the Treasury on September 12, 1977. She was the first, and so far is still the only, Black woman to serve in the office.

Aging and elder care may not be the first thing you think of when you think of social movements, but in 1970, the National Caucus on the Black Aged (now the National Caucus and Center on Black Aging) was formed to focus on issues important to the over-50 Black community, namely housing and health care. In attempting to promote their work, the NCBA asked the Carters to support a “Living Legacy Awards Ceremony.” The plan was to have Rosalynn host a luncheon with the potential for a POTUS drop-in, but President Carter went much bigger. Not only did he preside over the awards, but he also paid personal tribute to each awardee that had a historic and positive impact on the Black Community.

Splish, Splash

On April 20, 1979, President Jimmy Carter was fishing in his hometown of Plains, Georgia. Aside from his staff watching from the shore, he was at the lake alone – or so he thought.

He heard a splash in the water, turned around and saw that a rabbit had “jumped in the water and swam toward my boat. When he almost got there, I splashed some water with a paddle.” Press Secretary Jody Powell described it as “not one of your cutesy, Easter Bunny-type rabbits.”

“The President confessed to having had limited experience with enraged rabbits. What was obvious, however, was that this large, wet animal, making strange hissing noises and gnashing its teeth, was intent upon climbing into the Presidential boat.”

In a 2010 interview, Carter described the incident and the media circus around it as a “humorous and still lasting story.” One of the debates around the incident was whether rabbits could even swim. To that, Carter said, “Of course!” After the story was publicized, people who kept rabbits at home put them in their swimming pools and wrote to the White House validating his story.

The country will pay their respects to the late president during the National Day of Mourning on January 9, 2025, when President Carter will lie in state. Reflecting on Carter’s long, dynamic career certainly should inspire us all to lead with empathy and never back down from our principles.

Related Content